California Man Charged With Murder Even Though He Didn’t Fire A Shot

Last year, lawmakers repealed the felony murder rule, which allowed prosecutors to charge defendants with murders they didn‘t commit. Prosecutors are trying to overturn the new law, but AG Xavier Becerra believes that the reform should stand.

On Jan. 30, 2016, Dennis Wright and his girlfriend Kyndra Ghiorso brought 100 pounds of marijuana to the Beverly Lodge hotel in South Lake Tahoe, California, hoping to make a sale. But the buyer pulled out of the deal, and as they were preparing to leave, two men robbed them in the parking lot. Wright resisted, and one of the men, Dion Vaccaro, allegedly shot and killed him.

Police orchestrated a multi-state manhunt for Vaccaro and his alleged accomplice, Domenic Randolph. Authorities eventually arrested Vaccaro in Oklahoma and Randolph in Texas. Both were charged with first-degree murder.

The police also arrested four other men who allegedly helped plan the robbery: Tristan Batten, Tevarez Lopez, Andrew Adams, and Harvest Davidson. Instead of charging them solely with robbery, El Dorado County District Attorney Vern Pierson utilized California’s felony murder rule. Under the rule, all four could be convicted of murder if they were found guilty of participating in the robbery that led to it.

In November 2016, Batten entered a guilty plea to murder, but the three other men maintained their innocence. Two of those cases, which are still pending, are becoming tests as to whether the legislature’s repeal of the felony murder rule last year was constitutional.

For decades, anyone in California who participated in a felony crime like robbery that resulted in a murder could also be charged with first-degree murder—even if they didn’t take part in the killing or intend for anyone to die.

Adnan Khan, for example, was sentenced to life without parole in a deadly 2003 robbery even though the prosecutors, judge, and jury agreed that he did not plan or commit the murder.

But in 2018, legislators rewrote California’s murder law to get rid of the felony murder rule. Senate Bill 1437, which went into effect on Jan. 1, requires prosecutors to prove at least one of three elements to seek a murder conviction: that the person was actually the killer, or that they aided and abetted the actual killer with the intent of helping kill someone, or they acted as a major participant in a felony crime with reckless indifference to life.

California prosecutors lobbied aggressively against this new standard, but former Governor Jerry Brown signed SB 1437 into law.

Since SB 1437 went into effect, prosecutors have attempted to overturn it in murder trials by arguing that the law unconstitutionally amended two voter-approved initiatives. The courts are far from united on the legality of the measure. Judges in several trial courts have already issued opposing rulings. For example, a San Diego County judge tossed out murder charges against a man who allegedly served as a getaway driver during a fatal robbery at a gas station. And a San Luis Obispo County judge declined to hear petitions for re-sentencing of several people convicted of murder under the felony murder rule because he said that SB 1437 is unconstitutional.

Several cases have reached the appellate court level, including two of the men charged with murdering Dennis Wright.

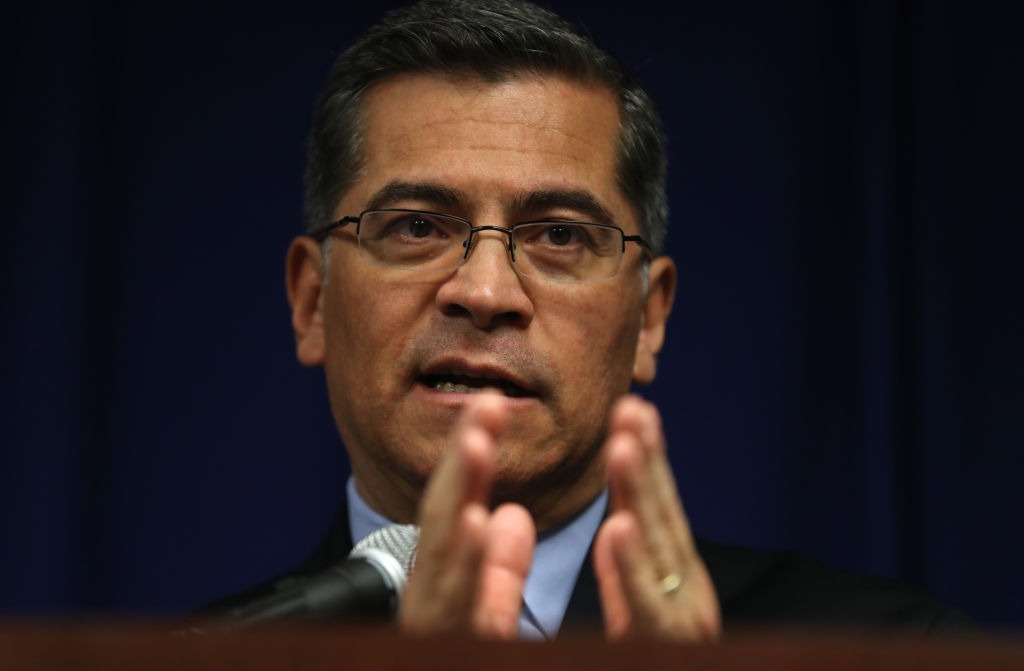

On July 12, state Attorney General Xavier Becerra submitted briefings in their cases in support of SB 1437. Becerra wrote that the measure doesn’t make changes to previous voter-approved propositions, as district attorneys and other opponents argue. Rather, the new law “changes the elements that must be proven to convict for the crime of murder.”

On July 22, Becerra tweeted of SB 1437 that “reforming the felony murder rule is a major milestone in the quest to make our criminal justice system fair and equitable” and that he is “proud to stand up and defend it in court.”

Dale Gomes, the El Dorado deputy district attorney handling the Wright case, wrote in an email to The Appeal that he would not discuss the case nor his office’s current position regarding SB 1437. But DA Pierson has been one of the most active DAs in the campaign to overturn the law. Last year Pierson wrote an op-ed in the Mountain Democrat that SB 1437 is “dangerous new legislation designed to severely limit and restrict the applicability of the Felony Murder Rule.” On Sept. 4, 2018, Pierson joined 41 other DAs to sign a letter from the California District Attorneys Association urging Governor Brown to veto SB 1437.

Sacramento-based defense attorney Jennifer Mouzis told The Appeal that DAs like Pierson have been able to seek murder convictions against people who never intended to kill anyone, and who didn’t actually aid and abet a murderer with the intent to kill. Mouzis said the felony murder rule has disproportionately affected Black and Latinx defendants, and contributed to the state’s mass incarceration crisis.

After SB 1437 was signed into law last year, Cottina Perry, the mother of Harvest Davidson, contacted Mouzis and asked her to represent her son. At first, Mouzis declined, but Perry refused to leave her office until she would agree to help. Perry had lobbied for SB 1437’s passage in hopes that it would help her son.

“She basically sat there until I took her case,” said Mouzis.

After reviewing the evidence, Mouzis concluded Davidson played no part in Wright’s murder.

According to evidence and testimony in the case, Davidson was part of a group that met with Wright and Ghiorso on Jan. 29, 2016, to set up the marijuana deal. The next day, just before the shooting, Davidson was with the alleged killers Vaccaro and Randolph, as well as accomplices Batten and Adams. But Davidson did not take part in the killing. He was in a car parked away from the hotel where Wright was shot. According to Mouzis, there was no evidence presented that Davidson knew Vaccaro planned to kill anyone, or that he in any way intended to aid and abet the murderer or Wright.

Still, under the old felony murder rule, all Davidson had to do was take part in the robbery, and be convicted of this crime, to also be convicted of murder. If SB 1437 is eventually deemed to be constitutional, however, Davidson would have to have helped in the robbery and done so with reckless disregard for human life in order to be charged with murder.

“Harvest [Davidson] never acted in reckless disregard for human life,” said Mouzis.

On Jan. 7, Mouzis sought a dismissal of the murder charge against Davidson based on SB 1437. But at an April 5 hearing, El Dorado County Superior Court Judge Gary Mullen ruled against the motion to dismiss. Mullen said that DA Pierson was correct: SB 1437 is unconstitutional because it attempts to modify two voter-approved ballot measures, Proposition 7 and Proposition 115. Mullen opined that these propositions can only be changed through new propositions or by a two-thirds vote in the legislature, a threshold that SB 1437 did not reach.

In 1978, voters approved Proposition 7, also known as the Briggs Initiative. It increased penalties for people convicted of first and second-degree murder, mainly by ensuring more death sentences and longer prison terms. The measure’s proponents, state Senator John Briggs of Orange County, former federal prosecutor Donald Heller, and Sacramento County Sheriff Duane Lowe invoked the specter of serial killers like Charles Manson, the Zodiac Killer, and the Hillside Strangler to convince voters to back their measure. (In the same election, Briggs also sponsored Proposition 6 which would have required schools to fire gay teachers.)

“This was the start of the tough-on-crime era,” said Kate Chatfield, a law professor at the University of San Francisco who helped write SB 1437, which was authored by state senator Nancy Skinner. (Chatfield is also a senior adviser to The Justice Collaborative, which publishes The Appeal.) “It was a very conservative period that led to mass incarceration in this country, and Proposition 7 very much started that movement.”

Proposition 115 was a sweeping package of laws known as the Crime Victims Justice Reform Act, supported in 1990 by State Senator Pete Wilson. It expanded the list of charges for which the death penalty could apply. It also added to California’s murder law by allowing prosecutors to seek the death penalty or life without parole for anyone who supports or aids a killer with intent to kill, or anyone who is a “major participant” in certain crimes like robbery which result in a death, if they acted with reckless indifference to human life.

Current law, even after enactment of SB 1437, still allows prosecutors to charge someone using Proposition 115’s guidelines.

Mouzis said the guidelines don’t apply to Davidson, who is being charged under the felony murder rule in Wright’s killing. On April 22, Mouzis filed a petition with California’s Third Appellate District Court, which is also considering the matter of SB 1437’s constitutionality.

The Davidson case is one of a handful of felony murder cases that could soon end up before the state Supreme Court. Its decision on SB 1437’s constitutionality will also affect thousands of people who were convicted under the felony murder rule and are petitioning to have their sentences vacated. Since January, the Los Angeles district attorney’s office alone has received over 1,100 SB 1437 resentencing petitions. The office recently issued a policy that ended most of its challenges to SB 1437.

Attorney General Becerra wrote in his July 12 brief that SB 1437 did not amend Proposition 7 or 115 and that therefore the law is constitutional. District attorneys, Becerra wrote, can no longer apply the felony murder rule to prosecute people who weren’t involved in the killing itself. Still, he disagreed with Mouzis about the appropriateness of a murder charge for her client. “The testimony presented at the preliminary hearing would lead a person of ordinary prudence to ‘conscientiously entertain a strong suspicion’ that petitioner was a major participant in the underlying felony that resulted in Wright’s death and acted with a reckless indifference to human life,” he wrote.

Mouzis believes that the evidence will show otherwise.

“If 1437 is constitutional, the most [Davidson] could ever be found guilty of would be robbery,” said Mouzis. “I’m not even sure he can be found guilty of that. He’s been in custody for so long the only thing justice can look like is letting him go home.”