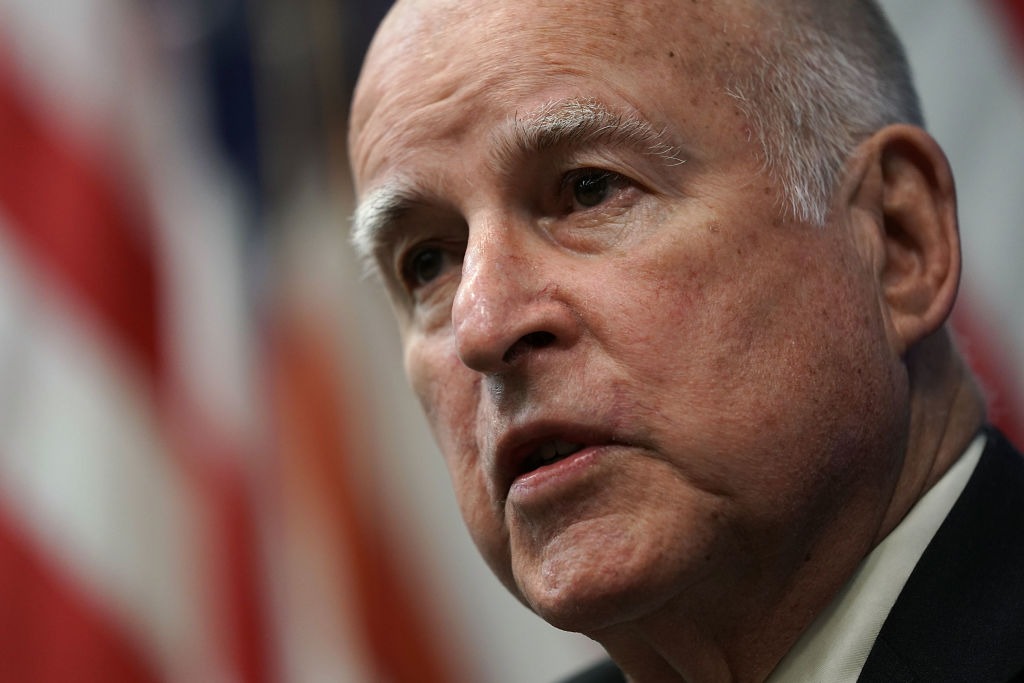

California Governor Jerry Brown is Fighting Trump With Pardons. Will Other Governors Follow Suit?

The departing governor has chosen to pardon immigrants whose past criminal offenses put them in danger of deportation.

Just before the Thanksgiving holiday last week, California Governor Jerry Brown pardoned 38 people, including three refugees from Vietnam who faced deportation. Tung Thanh Nguyen, Truong (Jay) Quang Ly, and Hai Trong Nguyen all came to the United States as children. As teenagers, they were convicted of crimes, which put them at risk of being deported.

But with Brown’s pardons—made more urgent as President Trump ramps up raids and deportations of refugees from Southeast Asia—they can stay.

Tung Thanh Nguyen served more than 16 years for brandishing a knife and acting as lookout during a murder. Jay Quang Ly was convicted of voluntary manslaughter for driving a car in which the passenger shot and killed someone, and served nine years. Hai Trong Nguyen was imprisoned for nearly 16 years for robbery involving a firearm.

All three men are now activists working on criminal justice reform efforts, including juvenile justice and prison re-entry programs for Asians and Pacific Islanders.

Governors have the power to stop many of these deportations with the stroke of their pen.

Angela Chan Asian Americans Advancing Justice – Asian Law Caucus (ALC)

Now that Governor Brown has pardoned these men—along with several other immigrants and refugees in recent months—they could fight a deportation order. Brown’s track record on pardons overall is unusual; since returning to office in 2011, he has granted more than 1,100 pardons, more than any governor in the state’s modern history. And advocates are hoping other governors will also use their executive clemency power to help halt deportations.

“Governor Brown’s laudable record on pardons should light a fire under other governors to do much more to protect immigrants targeted for deportation by the Trump administration,” Angela Chan, policy director and senior staff attorney with Asian Americans Advancing Justice – Asian Law Caucus (ALC) in California, told The Appeal. “Governors have the power to stop many of these deportations with the stroke of their pen.”

Last month, the Immigrant Defense Project (IDP) launched Pardon: Immigrant Clemency Project with an initial focus on getting clemency for immigrants in New York, including a hotline to help immigrants apply for pardons. Since 2017, Governor Andrew Cuomo has pardoned at least two dozen immigrants facing the threat of deportation and other immigration consequences.

“While President Trump engages in policies that rip children out of the arms of their mothers and tries to ramp up the deportation of New Yorkers to advance his political agenda of hate and division, we will protect our immigrant communities,” Cuomo said in a July 2018 statement upon pardoning seven immigrants.

Our campaign is a national campaign.

Jane Shim Immigrant Defense Project

The Immigrant Defense Project hopes Cuomo will grant even more. Jane Shim, advocacy staff attorney at IDP, said the organization’s clemency campaign hotline has received hundreds of phone calls. “The amount of interest makes clear how much the need is, for people who have prior criminal justice involvement of any kind.”

IDP doesn’t plan to stop with New York. “Our campaign is a national campaign,” said Shim. One of the project’s goals is to make the pardon process more accessible to immigrants through a pardon toolkit meant to be useful in any state. Next year, IDP hopes to bring the project to other states, building off the momentum from California.

In California, there’s still time for Brown to issue more pardons before leaving office in January. His office told The Appeal there are more pardons to come. That gives hope to Somdeng Danny Thongsy, a criminal justice reform advocate in Oakland who works on clemency campaigns for immigrants and is seeking a pardon of his own after receiving a final order of deportation from ICE.

Thongsy, a refugee whose family fled Laos, served 20 years in prison for a fatal shooting. Since his parole from San Quentin in December 2016, he has worked on re-entry programs, through which he knew some of the men just pardoned.

“Just seeing all of their names on there, to me, I was really happy,” Thongsy told The Appeal.

Like many Southeast Asian immigrants facing deportations as a result of past criminal offenses, Thongsy has never returned to his country of origin and doesn’t have family there. His family left Laos after it was bombed during the Vietnam War, and Thongsy was born in a refugee camp in Thailand, arriving in Northern California when he was a child.

Someone who served their time should not be punished again, and that’s what deportation is. It’s a double punishment.

Somdeng Danny Thongsy criminal justice advocate seeking a pardon

Angela Chan at ALC says there’s a reason Trump’s plans are hitting Asian immigrant and refugee communities in California so hard. As their families were resettling in the state after fleeing war in Vietnam and Laos, and genocide in Cambodia, California’s prison system was growing. The state passed three-strikes laws along with harsher penalties for young people in the system, and the number of people incarcerated soared. Criminal arrests for Asian American and Pacific Islander youth increased by more than 700 percent between 1977 and 1997, according to ALC.

Chan said although her organization recognizes Brown’s record on pardons, “we also want to point out that California is guilty,” she said. “It’s part of the reason why Southeast Asian refugees are in this crisis. And [Brown] had a hand in it, based on his prior record with helping to build our criminal justice system, both as attorney general and as a four-term governor.” In a recent statement, a spokesperson for Brown’s office acknowledged that the pardons were, in part, “a recognition of the radical and unprecedented sentencing increases and prison building boom of the ’80s and beyond.”

While Brown has supported legislation like Senate Bill 54, California’s sanctuary law (now the target of a Trump administration legal challenge), and Assembly Bill 2845, which makes the pardon and commutation process more transparent, the state’s prisons and jails continue to aid Trump’s deportation agenda.

Thongsy experienced that complicity firsthand. When he left San Quentin nearly two years ago, he was transferred directly into ICE custody, and stripped of his green card.

If he were pardoned, Thongsy said, it could help change his relationship with his family and allow him to continue his work helping people transition out of life in prison. “Someone who served their time should not be punished again, and that’s what deportation is. It’s a double punishment,” Thongsy told The Appeal. “A person is not only going to be deported, their family is going to suffer and the community as well.”