California could soon end money bail, but at what cost?

The passage of Senate Bill 10 would decimate the bail industry, but many advocates say it falls short of true reform.

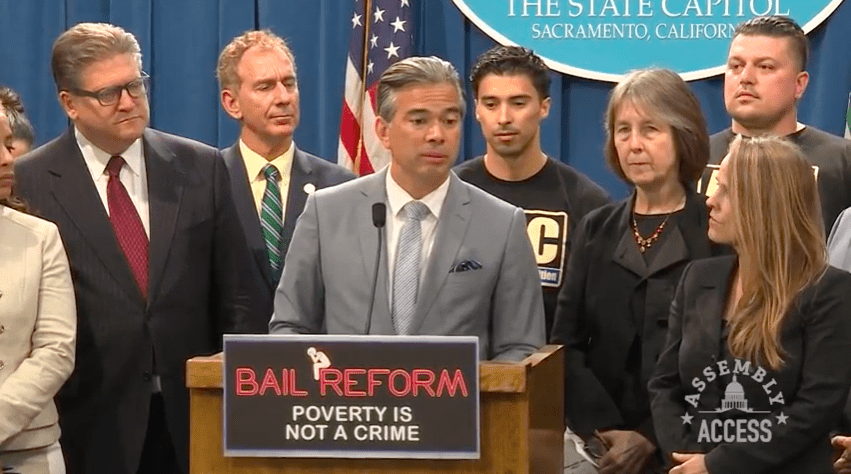

This week, California took a major step toward eliminating cash bail and dealing a significant blow to the predatory bail bond industry when Senate Bill 10, which would replace cash bail with a risk-based system, passed the state Assembly and Senate. It appears almost certain that Governor Jerry Brown will sign it into law.

While some bail reform advocates hailed the victory as a milestone, others say the bill could actually increase the number of people detained pretrial.

“The new version essentially replaces the evils of money bail with a worse evil known as preventative detention,” San Francisco Public Defender Jeff Adachi wrote in an editorial in the Sacramento Bee that blasted the legislation. “This is not the bail reform California needs.”

In earlier drafts of the bill, all defendants would have appeared before a judge with a presumption of release. To detain someone, prosecutors would have had to make a case with convincing evidence that there was no way to release the person while ensuring his or her next court appearance and protecting public safety.

This month, however, a new draft of the legislation began making the rounds that vastly altered its vision and scope. While abolishing cash bail and mandating the release of most people arrested for nonviolent misdemeanors within 12 hours of being booked, the new draft gives county judges wide-ranging discretion over which defendants deemed “medium risk” could be detained pretrial.

The bill also creates broad categories of defendants who could legally be detained without prosecutors having to make an argument about why. Under the current system, even those charged with serious crimes have the presumption of release, albeit often with bail attached. Under the new system, these categories of defendants would automatically be presumed for “preventive detention” instead, flipping the burden of proof onto defense attorneys, who could still argue for their release. The categories include individuals charged with violent felonies, anyone convicted of a violent felony within the past five years, anyone deemed by a risk assessment tool as a “high risk” to public safety, or anyone on supervised probation.

Supporters of the current bill believe the changes were necessary to gain support from both the state’s Judicial Council, the rule-making arm of the California court system, as well as Governor Brown, who had pegged his support of a bill to whether the state’s judges were behind it. The Judicial Council, in a report released last October, called for an increased discretionary role for judges in determining who could safely be released. The Judicial Council and county courts across the state now will have until Oct. 1, 2019, to implement the new system.

“Ultimately the Judicial Council and the chief justice got the pretrial structure that they wanted,” said Anne Irwin, director of Smart Justice California, an advocacy organization that once supported the bill but has now taken a neutral position. “We know their support mattered immensely for Governor Brown.”

Yet the current bill is a grave disappointment to many advocates who initially fought for the legislation. Within days of the new draft’s circulation, groups like Human Rights Watch, the California Public Defenders Association, and the NAACP dropped their support. On Monday, the ACLU, after taking a neutral stance toward the altered legislation, shifted its position to one of opposition.

Chesa Boudin, a deputy public defender in San Francisco who has worked on litigation challenging cash bail in the state and who was on the advisory committee to the drafters of the original bill, says the new bill penalizes people regardless of guilt, not unlike the bail system it was intended to replace. “It creates a system where, by law, California would punish people just for being arrested, rather than waiting until they’re convicted of a crime.”

Advocates are also concerned about the role of risk-assessment tools, which help judges weigh a person’s likelihood of absconding or posing a threat to public safety. A previous draft of the bill used risk assessments to determine a defendant’s conditions of release (such as where the person could travel or whether he or she had to wear an ankle monitor). In the bill that passed the legislature, these tools could be used by judges to determine whether a person should be released. While that’s not uncommon around the country, it is often contested. Many reform advocates argue that risk assessments rely on data, such as employment and criminal history, that’s tainted by discrimination. In communities of color that are overpoliced, for example, there are likely to be more people with prior arrests.

The Superior Court in each county will be allowed to choose their own risk-assessment tools from a list approved by the Judicial Council and decide independently which charges should automatically result in detention hearings, which could lead to huge variations across the state. Statewide, most defendants who have been given a “low risk” designation by the risk-assessment tool will be automatically released.

“The fate of pretrial incarceration in California is now in the hands of judges,” Irwin said.

While that leaves many unknowns, Irwin says, there are reasons to worry. Earlier this year, Judge Aaron Persky was recalled after he handed out what was regarded as a “lenient” sentence to a man found guilty of sexual assault. It was the first judicial recall in California in more than 80 years, and Irwin says it may cause judges to think twice before choosing less punitive options for defendants.

“Right now, judges, for the first time are looking over their shoulders, and when they exercise their discretion to give what is perceived to be leniency to defendants, they now risk losing their jobs,” Irwin told The Appeal. “You have to question the theory that judges are going to exercise the discretion given to them by SB 10 in a way that actually releases more defendants pretrial.”

She said judges could also be motivated to keep defendants detained in order to better manage caseloads—the longer people are detained, the more likely they are to take a plea deal. In addition, if a judge wants to schedule a hearing on short notice, the defendant can readily be produced in court.

The question of whether risk assessments are a reasonable trade-off for bail reform is complicated. In New Jersey, whose jail population dropped 20 percent after it abolished cash bail in 2017, judges use analytic tools to inform their decisions about pretrial release, though state law ensures that a relatively broad group of defendants are given the presumption of release.

Informed by an algorithm or not, judges still bear the most responsibility for deciding who should be released, argues KiDeuk Kim, a senior fellow in the Justice Policy Center at the Urban Institute who has studied the use of risk assessment programs across the country.

“The tool is meant to help with resource allocation,” Kim said. “[Judges] can decide who to put in jail or release to the community depending on their ability to supervise them in the community. It depends on the jurisdiction’s capacity … [the judges] can decide the threshold.”

In some other cities that have restricted the use of cash bail, judges have been reluctant to take chances. In Baltimore, the jail population rose between March 2017 and March 2018 after judges were instructed not to set bail for people who couldn’t afford it beginning in January 2017. Instead of releasing arrestees without monetary conditions, however, judges opted instead to detain more people.

Reformers fear the same rise in detention could happen in California.

The bill still faces stiff opposition not only from former supporters, but from the state’s law enforcement and bail bond lobbies, for different reasons. California’s bail industry stands to lose hundreds of millions of dollars per year. The median bail amount in the state is $50,000 dollars, over five times that of the rest of the country.

“We’ve slayed one big dragon,” Irwin said. “The predatory bail industry will … in effect be eradicated, as well as wealth-based detention. The most laudable victory here is one of economic justice, and that is a giant step forward.”

Both the bill’s supporters and opponents are committed to improving it. Some advocates and lawmakers are already working on legislation to improve its data collection mechanisms, and root out the racial bias often inherent in risk assessments.

“There is a lot of additional work to be done as it related to how this bill will be implemented,” said Lenore Anderson, executive director of Californians for Safety and Justice, an organization that supported the bill through its passage. “The implementation process will be key in developing how the new pretrial system unfolds. … We are going to be actively engaged and involved, and rolling up our sleeves to make sure that the goal that we all want is achieved, which is a fair pretrial system and reducing unnecessary incarceration. ”