#ByeCy: Organizers call for embattled Manhattan D.A.’s resignation

A movement to oust Cyrus Vance gains steam.

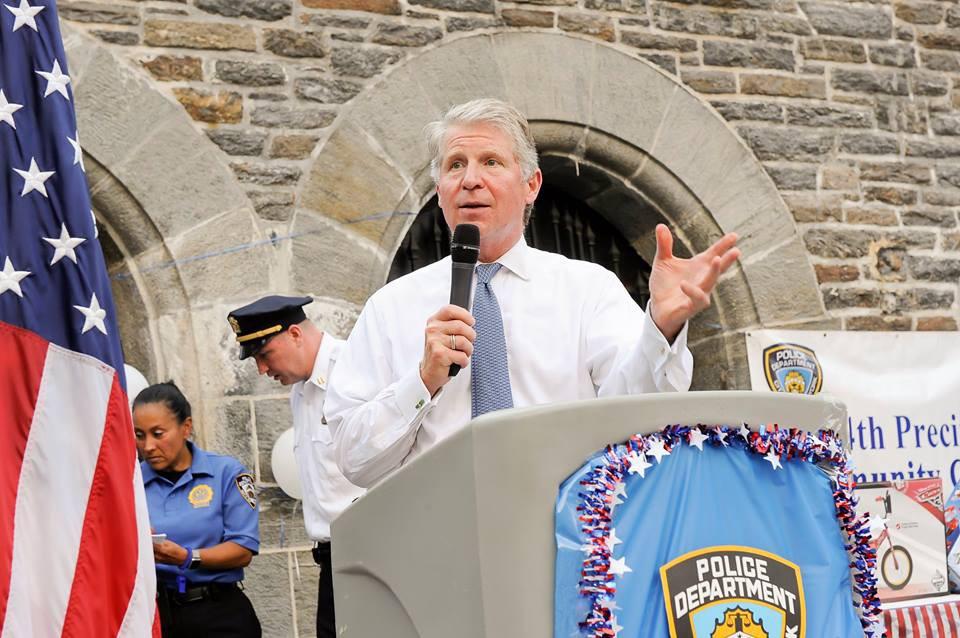

Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance’s failure to prosecute Harvey Weinstein, along with Donald and Ivanka Trump, scandalized many New Yorkers last week. How could the man elected to bring justice to the city’s second-most populous borough so baldly turn the other cheek to illegal activity? How could this progressive prosecutor, who on Wednesday admonished Trump for his archaic, punitive criminal justice policies, accept questionable campaign donations from lawyers representing the city’s wealthiest elites?

For many of the city’s public defenders and community organizers, these unflattering revelations were hardly a shock. Instead, the news was seen as an opportunity to draw attention to issues in the D.A.’s office that many have called out for years.

“There seems to be momentum to ask for [Vance’s] resignation, and people from a wide swath of political backgrounds are outraged,” says Zohra Ahmed, a member of the public defender coalition 5 Borough Defenders, a group that challenges what they call “injustices of the criminal legal system.”

On Thursday, the 5 Borough Defenders and three other community-based organizations are hosting a rally at one of Vance’s two downtown Manhattan offices to say “#ByeCy.” Ahmed and her fellow organizers are calling for his resignation, and hope to spark a broader conversation about what it means to be a “progressive” prosecutor. Vance is running unopposed in the Nov. 7th election, making his third term almost inevitable. (Marc Fliedner, a former prosecutor who lost in the primaries for Brooklyn D.A., is running as a write in candidate in the Manhattan race, but is not endorsed by the #ByeCy coalition.)

In addition to asking Vance to step down, the rally organizers hope to draw attention to a list of ten issues that they say make him unfit to be D.A. Chief among those is what they say are the D.A.’s disparate charging practices.

“What we’re hoping to bring to bear is the discrepancy between the charging decisions made about people like Weinstein and the Trumps, and the vast majority of defendants who are indigent,” Ahmed tells The Appeal. “The revelations really highlight a two-tiered system of justice.”

One of the clearest examples of that two-tiered justice system is a policy that is not isolated to New York City: the D.A.’s use of cash bail. Hundreds of thousands of people across the country are in jail on any given day because they can’t pay their bail. Of the 646,000 people held in local jails nationally, 70 percent have not been convicted of a crime and are being held pretrial. On an average day in New York City, roughly 4,000 or slightly over half the city’s jail population is incarcerated because they’ve been unable to post bail, according to the city’s Independent Budget Office. Cash bail offers an opportunity for those who can afford it to pay for their freedom, while the rest of the accused wait behind bars.

In August, dozens of current and former law enforcement officials, including Vance, signed a friend-of-the-court brief opposing the use of cash bail for people accused of misdemeanors. The brief was filed in support of a lawsuit challenging Harris County, Texas’s cash bail practices. To Rachel Foran, managing director of the Brooklyn Community Bail Fund, Vance’s choice to sign the brief is curious in light of what’s happening in his own office. Since he signed, Foran says her organization has bailed out 125 misdemeanor defendants in Manhattan.

“He is calling for the end of money bail in a different state, and yet his office is continually requesting high and low amounts of bail for folks who can’t afford it,” says Foran.

That discrepancy between what Vance says and what his office does is a driving force behind the #ByeCy initiative. It’s an issue cropping up nationally: While an increasing number of local district attorneys are running campaigns on reform-driven platforms, fewer are following through.

Given that “the main problem-solving tools a prosecutor has are prosecution and incarceration,” the notion of a prosecutor “being progressive is in itself a bit complicated,” says Ahmed. A sincerely progressive prosecutor, she continues, would “acknowledge that many issues should not be dealt with in the criminal justice system…You need prosecutors who are shrinking their own power, which is very difficult to imagine.”

Ahmed admits Vance’s voluntary resignation is unlikely. (At the time of publication, the Manhattan D.A.’s office had not responded to a request for comment.) But with all eyes on Vance, she and her cohort see this as an ideal moment to put significant public pressure on his office.

“At the very least, we’re hoping there could be a spirited democratic debate about what makes an accountable, truly progressive prosecutor,” says Ahmed. “New Yorkers all stand to benefit from pushing Cy Vance to a better position.”