Brooke Jenkins Can’t Have It Both Ways

The new San Francisco DA is mixing “tough-on-crime” rhetoric with phony progressivism. Neither will solve the city’s problems.

This piece is a commentary, part of The Appeal’s collection of opinion and analysis.

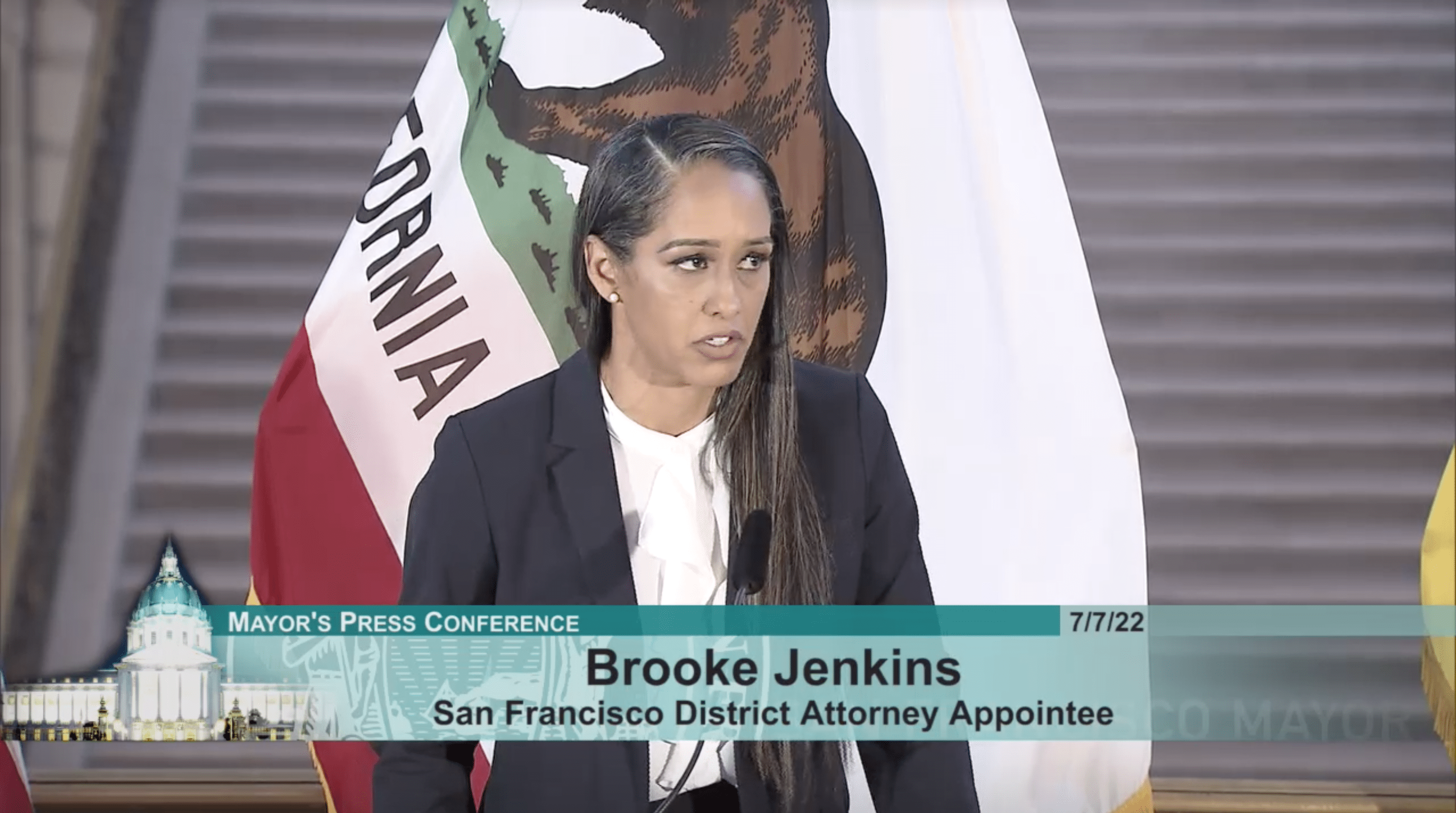

Since her appointment as San Francisco District Attorney, Brooke Jenkins has tried to temper her tough-on-crime rhetoric by claiming that she believes in reform, too.

After publicly exiting the DA’s office in 2021, Jenkins became the face of the ultimately successful effort to recall her former boss, District Attorney Chesa Boudin. During the campaign, Jenkins gave cover to “liberal” white San Franciscans who favored harsher approaches in a legal system that disproportionately harms people of color.

But even as Jenkins built her tough-on-crime credentials, she claimed she would achieve both safety and reform. Local media largely played along, even though Jenkins’s record and her initial actions as DA resoundingly contradict that claim. Since becoming DA, Jenkins has struggled to point to a single reform she supports.

Although Jenkins has described herself as a “progressive prosecutor,” this is a term of art used to delineate a movement of decarceral, reform-minded prosecutors, including Boudin. It is not “progressive” to call for increased “consequences” (read: incarceration) for property crimes, or more “accountability” (read: incarceration) for drug dealing. Using the term in this way renders it completely useless. Jenkins may be hoping to use “progressive” vibes to mask a regressive criminal justice approach, but this is a slap in the face to those of us who worked in the trenches to advance the reforms she is now undoing.

Moving Backwards

During Boudin’s administration—in which I proudly served—San Francisco saw a nearly 40-percent reduction in the jail population, historic efforts to hold police accountable, and increased support for crime survivors.

Upon taking office, Jenkins moved quickly to abandon and undo Boudin’s most impactful reforms.

She started by firing 15 staffers in a single day. My termination was somewhat predictable (I was Boudin’s communications director and policy advisor). But Jenkins also fired the lawyers reviewing excessive prison sentences, those prosecuting police officers, and the data director who promoted public transparency. She also demoted the Chief of Victim Services, who had expanded language access for victims from the Asian American Pacific Islander community.

Jenkins’ appointment has also triggered resignations, including four victim advocates, one prosecutor, and a longtime staffer. Most of these staffers were hired before Boudin. Many more have told me they’re looking to leave.

Jenkins has said she wants “discretion” to set cash bail and charge kids as adults. She has attacked Boudin’s policies limiting gang and strike enhancements, and ridiculed his use of diversion programs. After almost a month in office, Jenkins has yet to clarify her new policies in these areas, and has dodged questions about what changes she’ll make. Her refusal to detail specifics has allowed her to conceal her lack of commitment to reform.

The Limits of Tough Talk

Despite Jenkins’s mantra that she will bring safety and reform to San Francisco, a tough-on-crime approach will achieve neither.

While campaigning for the recall, Jenkins claimed the city’s crime issues were “directly linked” to the DA’s policies, and happily joined critics in blaming Boudin for almost everything bad that happened in San Francisco.

But Jenkins changed her tone once she was announced as Boudin’s replacement. In an interview with the New York Times, Jenkins asked the public to “be patient” and “temper their expectations” about her ability to address the very problems she had been so quick to lay at the feet of Boudin. “No district attorney can snap their fingers and do away with all crime,” Jenkins admitted.

Now that it no longer benefits Jenkins to hold the DA responsible for crime—she is up for election in November—she has been forced to acknowledge the more complex realities of the job.

Despite her posturing during the campaign, Jenkins must know that the criminal legal system is ill-suited to address many of the problems the recall campaign exploited to attack Boudin. Homelessness, dirty streets, and visible substance use may be frustrating to many in the city, but the district attorney lacks power to substantively tackle these problems. What happens when San Franciscans notice Jenkins isn’t fixing them?

Jenkins already seems to be trying to move the goalposts. In a San Francisco Standard interview last month, she said her “benchmark” for success would be “what the residents of San Francisco feel.”

It’s telling that Jenkins wants to be judged on intangible feelings rather than concrete results. Amid incessant fearmongering by law enforcement and the media, public perceptions of crime and safety have become largely divorced from reality. Even if her tough rhetoric does nothing to improve actual safety in San Francisco—and there’s no reason to believe it will because incarceration does not promote public safety—Jenkins is banking on it at least making voters feel safer. It’s a cynical strategy. But in the current political environment, when feelings increasingly don’t seem to care about facts, it could be effective.

What’s Next for Criminal Justice in San Francisco?

There is no question that the resurgence of a “lock ‘em up” mentality will perpetuate harms against those who always suffer most from punitive criminal justice policies—particularly people of color, who have borne the brunt of mass incarceration and the drug war.

But in addition to causing harm, this approach bodes practical disaster for San Francisco. The city’s jails continue to suffer from woefully inhumane conditions, despite years of declining populations. Recent reports suggest these facilities lack the space and staffing to accommodate an increased reliance on incarceration.

The criminal courts—already facing a lengthy pandemic-related backlog—are no better equipped for an influx of cases. Without reasonable plea offers, low-level cases will only further bog down the system, making the swift “accountability” Jenkins champions even harder to achieve.

Nonetheless, Jenkins used her first day in office to announce a new policy prioritizing drug crimes. Though Jenkins was skimpy on details, the message was clear: The War on Drugs is back in San Francisco. Within days, her office had filed 17 stand-alone charges for possession of drug paraphernalia—the first such charges in years. After public backlash, Jenkins announced she would dismiss those cases, claiming they were filed without her approval. This week Jenkins announced new directives that would deny some drug defendants access to diversion programming. She also said she intends to seek pretrial detention for some people charged with selling drugs—potentially in violation of state law.

Jenkins also talked tough on drugs at a July press conference in the Tenderloin, where she spoke about the need to “clean up” the neighborhood. During her appearance, journalists reported that people continued to openly sell and use drugs just across the street, apparently unmoved by Jenkins’s rhetoric. Like its predecessors, the latest War on Drugs is destined to fail—and leave devastation in its wake.

Now Jenkins is in the hot seat. By the standard she and her fellow recall supporters set, the issues she previously blamed on Boudin are now hers to solve—or not. San Francisco’s streets remain dirty and unhoused people still have nowhere else to live. Crimes continue to happen under her leadership, ranging from gun homicides and assaults of elderly people in the AAPI community to Walgreens thefts caught on video.

So far, Jenkins has offered mostly rhetoric in response, as she tries to preserve her reputation as both “tough-on-crime” and a reformer. But Jenkins can’t have it both ways. Tougher rhetoric and policies won’t make San Francisco any safer. And phony progressivism won’t bring reform.

It’s only a matter of time before San Francisans realize they’ve been sold a bill of goods.