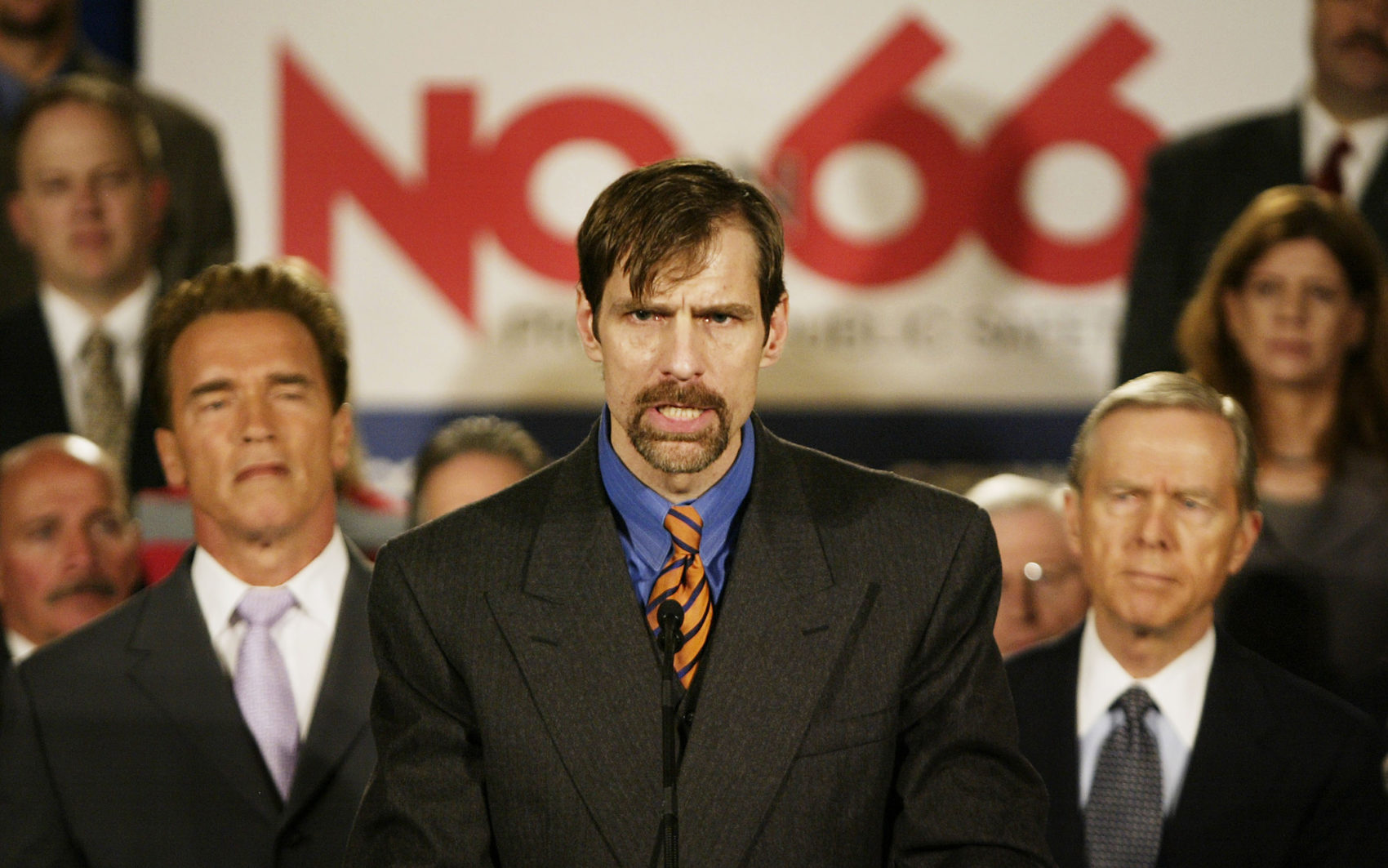

Billionaire Victims’ Rights Advocate Finds Himself at the Defense Table

Spotlights like this one provide original commentary and analysis on pressing criminal justice issues of the day. You can read them each day in our newsletter, The Daily Appeal. This month, billionaire Henry T. Nicholas III, who made his fortune as a co-founder of the semiconductor firm Broadcom, was arrested in Las Vegas for narcotics trafficking […]

|

Spotlights like this one provide original commentary and analysis on pressing criminal justice issues of the day. You can read them each day in our newsletter, The Daily Appeal. This month, billionaire Henry T. Nicholas III, who made his fortune as a co-founder of the semiconductor firm Broadcom, was arrested in Las Vegas for narcotics trafficking after police found heroin, cocaine, meth and Ecstasy in his hotel suite. He hired David Chesnoff, “perhaps Las Vegas’ best-known defense lawyer,” according to the Los Angeles Times, and was soon released without having to post any bail. The district attorney, Steve Wolfson, later offered Nicholas a plea deal that would allow him to avoid prison. Nicholas was expected to enter an Alford plea yesterday, meaning he would maintain his innocence but acknowledge that there is sufficient evidence to convict him, on a single count of possession of a controlled substance. “Rather than attend drug court, which requires intensive treatment and drug testing, the deal calls for Nicholas … to participate in two drug counseling sessions a month, perform 250 hours of community service during the course of a year, and pay $500,000 to a yet undetermined drug treatment facility in Las Vegas,” according to the Nevada Current. “Failure to comply will result in a finding of guilt on one count of possession, a probationary charge, meaning [Nicholas and his co-defendant] will avoid prison regardless of their compliance.” Some, including one anonymous courthouse insider, believe that Nicholas paid his way out of jail time. “What it shows is that we have two systems of justice in our state,” Assemblymember William McCurdy, who is chairperson of the Nevada Democratic Party, told the Current. “We have a system for those who have wealth and one for those who do not.” Ironically, the Nevada District Attorneys Association supported an amendment that would have brought harsher penalties to defendants like Nicholas. “During the last session, on a variety of criminal justice reform bills, we saw district attorneys … consistently ask for more discretion and power [including] options for leniency,” said Assemblymember Howard Watts. “This case kind of illustrates when the discretion and leniency is applied in a regressive and inequitable manner.” None of this would be particularly remarkable or newsworthy if it weren’t for the fact that Nicholas has been using his fortune to bankroll a pet project: Marsy’s Law, a victim’s rights ballot measure named for his sister, who was murdered by an ex-boyfriend in 1983. Nevada voters overwhelmingly passed Marsy’s Law last November, and as of June 2019, Marsy’s Law had been passed in California, Illinois, North Dakota, Ohio, Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, Nevada, Oklahoma, and South Dakota. Nicholas’s goal is to have it passed as an amendment to the U.S. Constitution. But Marsy’s Law has drawn criticism not only from the defense community, but also from prosecutors and some victims’ rights advocates. The measure grants victims of all crimes, including misdemeanors and other low-level offenses, a “sweeping array of rights, including the right to be notified of any public hearing involving the crime,” according to the Marshall Project. “It also has drastically broadened the definition of ‘victim’ to include, in some states, ‘any spouse, parent, grandparent, child, sibling, grandchild, or guardian’ of that person.” Because of its breadth, Marsy’s Law is expensive and almost impossible to follow. Some prosecutors and victims’ rights groups say its requirements can hinder investigations and dilute services for people who need them most. “Defense attorneys argue it upends the presumption of innocence, giving alleged victims a say before it has been established that there was a crime in the first place. Using Marsy’s Law, prosecutors have blocked defense attorneys from getting basic information, such as where a crime took place.” Voters overwhelmingly approved the measure in South Dakota in 2016, but sheriffs have now “stopped asking for the public’s help in solving crimes-in-progress to avoid inadvertently revealing a victim’s location,” reports the Marshall Project. “Prosecutors spent hundreds of thousands of dollars beefing up staff to find victims of low-level misdemeanors, such as vandalism or shoplifting. Defendants have spent additional days in jail because the prosecutor can’t locate victims in time for an arraignment, according to prosecutors and defense attorneys.” Two states that initially adopted Marsy’s Law, Montana and Kentucky, later overturned it. According to Forbes, Nicholas has a fortune of $3.1 billion, and the Marshall Project reports that he is “known for his flamboyant tastes,” including “private jets, multi-million dollar homes, a Lamborghini,” and also a “4,000-foot warren of tunnels and lavish man-caves he had built beneath his California mansion.” Nicholas has faced accusations before. He was indicted in 2008, and charged with providing cocaine and Ecstasy to friends and business associates, as well as installing “a secret and convenient lair” at his home in Laguna Hills to indulge an obsession with sex workers. Nicholas’s ex-wife has accused him of threatening to have her killed, according to a petition she filed during divorce proceedings, and in 2016, two ex-girlfriends went to court against him, one alleging assault and battery and emotional distress. Her case was later dismissed. Another was granted a temporary protective order after accusing Nicholas of rubbing feces in her face and punching her in the head. Despite the flurry of accusations, Nicholas has had tremendous luck with the legal system. It has treated him, it seems, leniently. In 2008, after charges against him were dropped, he said, “I have long held a deep and abiding faith in the American justice system.” “The Henry Nicholas plea deal is what is wrong with the criminal justice system. How many of the people passing through the Clark County Detention Center will get the same plea offer?” asked ACLU Nevada Executive Director Tod Story in reference to the recent agreement. The question may not be as rhetorical as Story anticipated. Rather than decry lenient treatment, which can often lead to worse outcomes for less advantaged defendants, public defenders in Las Vegas decided to ask prosecutors to grant terms similar to Nicholas’s, for all of their indigent clients. The Nevada Independent reports that attorneys drafted a plan to file motions in criminal cases that draw a direct comparison to the plea deal reached with Nicholas and the treatment of low-income defendants, including asking for a reduction in sentence, release without any bail, “and a contribution of 0.0128 percent of their net worth — the same percentage of Nicholas’s net worth that he agreed to pay as part of his plea deal.” The draft motion states: “Billionaire Defendant Nicholas and Defendant XXX are similarly situated and should be similarly treated by the prosecution and the courts. The primary difference between the two men is that Billionaire Defendant Nicholas is wealthy, while Defendant XXX is not.” Public defenders also drafted a form motion for cases where prosecutors offer a less favorable plea deal than the one offered to Nicholas, asking a judge to recuse the district attorney’s office based on the “appearance of impropriety and unfairness,” which erodes the public trust, such that appointment of a special prosecutor is warranted. “The appearance of impropriety and the bias is most obviously seen in the overly harsh plea bargain the State has offered the indigent defendant versus the sweetheart deal afforded the Billionaire Defendant Nicholas,” the draft motion states. “In this case, it seems clear that the criminal justice system, wealth rather than culpability shaped the outcome.” |