Baltimore’s ‘Eye in the Sky’ Plane Is Back With A New Pitch: Surveil The Police

Dismal police accountability has made communities vulnerable to private vendors.

Throughout 2016, a surveillance plane flew above Baltimore recording large portions of the city in secret—until a Bloomberg Businessweek story exposed the plane that August and shocked the city’s residents.

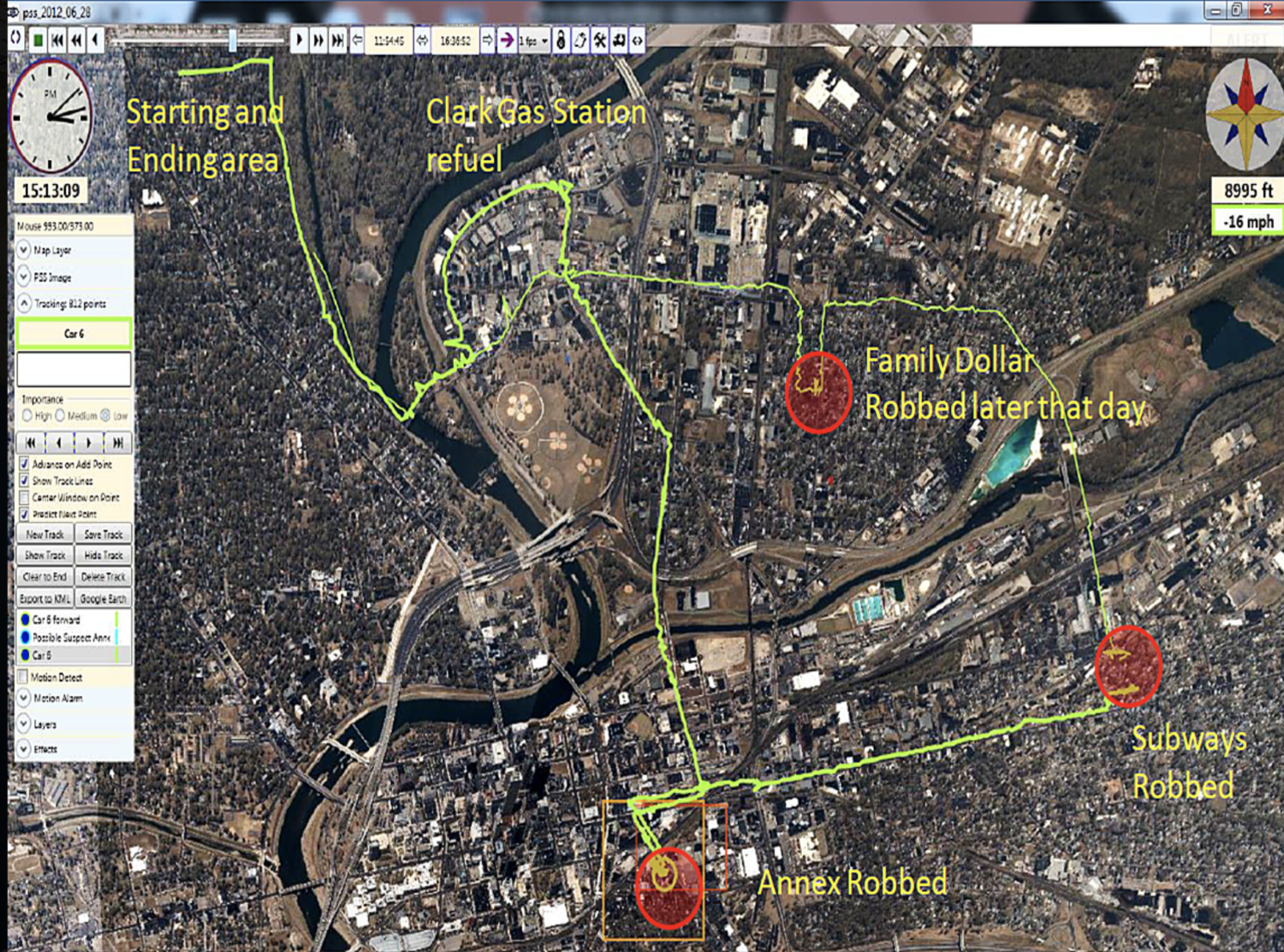

The plane was equipped with a dozen cameras, flew 8,500 feet in the air, and recorded Baltimore at about 30 miles at a time, creating a permanent record of every person’s movements that could then be zoomed in, rewound, and fast-forwarded. While the resolution is low—each person is just a speck on a screen—the plane works in concert with other surveillance to assist in investigating crimes, especially homicides, according to its Ohio-based developer, former military technologist Ross McNutt.

While a spy plane recording everything for extended periods of 2016 without public knowledge was surprising enough, the details made it seem even more nefarious: The plane was funded by billionaire philanthropists in Houston, Laura and John Arnold, who made a donation to a nonprofit that could then funnel the money to police. The plane’s footage, owned by McNutt, was shared directly with police. Only McNutt, his technicians, its private funders, and the Baltimore police knew about the operation; even the mayor and City Council found out with the rest of the city, and the state’s attorney’s office learned of it just a week before the article appeared.

Now, McNutt wants to bring his plane back to Baltimore—with an unusual new pitch. He’s working with residents frustrated with a notoriously corrupt police force in a city that the FBI declared one of the nation’s most violent to drum up support for the surveillance plane’s return.

“We hold police accountable. We provide unbiased information as to police activities. We can go back in time and see what happened at the scene of an incident,” McNutt said at a recent public hearing. “Just as we can deter potential criminal misconduct, we can also deter potential police misconduct.”

At a moment when trust in Baltimore police is exceptionally low, the idea of high-tech accountability is enticing to some residents.

“We have a [police] department that’s in disarray,” resident Archie Williams told The Appeal. “I’m tired; I’m fed up. I’m tired of depending on city leadership. … So I basically took this on myself and spread awareness as much as I could.”

Williams is a co-founder of Community With Solutions, an organization that supports the return of the surveillance plane because, he says, it will help solve homicides like the ones happening daily in his neighborhood. Baltimore is set to end 2018 with well over 300 homicides—for the fourth year in a row—while the homicide clearance rate hovers a little over 50 percent. McNutt has acknowledged that he has paid Williams a few thousand dollars.

Police accountability in Baltimore is particularly poor. A 2016 Department of Justice report released after the death of Freddie Gray in police custody was a lengthy list of police misconduct, dysfunction, racism, transphobia, and excessive force. The city is under a consent decree. Members of the city’s Civilian Review Board recently accused police of obstructing its ability to do its job. Suspicions were further inflamed by the Gun Trace Task Force scandal, in which eight police officers were federally indicted this year for robbing citizens, dealing drugs, and stealing overtime.

All of this has created a distrust in city officials that leaves communities more vulnerable to private vendors’ pitches. If the plane gets accepted in Baltimore, it could set a precedent to put the “eye in the sky” in more cities.

‘He’s a salesman’

Even before 2016’s secret flights in Baltimore, McNutt’s program received pushback from the communities it intended to surveil. In 2012, the plane flew secretly for nine days in Compton, California, without the citizens or government knowing; when it was revealed, it was roundly denounced. In 2013, it was proposed in Dayton, Ohio, home of McNutt’s Persistent Surveillance Systems, but a hearing brought widespread concerns and the plan for the plane died.

Once he realized community backlash was a major obstacle, McNutt began going directly to Baltimore residents to make his pitch in 2017. He brought presentations to churches, schools, recreation centers, and other public spaces. Williams attended a presentation in his neighborhood and has since become one of the most vocal supporters of the program. Since then, Williams has helped promote the plane, conducting over 30 presentations with McNutt around the city.

During a presentation in August, McNutt referred to his aerial surveillance program as the “Community Support Program”—the sunnier name he used interchangeably with Persistent Surveillance Systems in 2016. He and Williams argue that the footage could help defense attorneys as well as police.

“This is a tool, not necessarily just used to catch a criminal. But it also can prove that a criminal was innocent, so it helps both sides,” Williams told The Appeal, describing how he pitches the technology to Baltimore residents.

Baltimore City public defender Todd Oppenheim, whom McNutt gave a tour of the plane in 2016, does not think the footage collected would be that convincing or is even of particularly useful quality to aid criminal defense because “it’s just not that good.”

David Rocah of the ACLU of Maryland said McNutt’s technology would have little effect on catching or stopping police misconduct.

“I can’t think of a single incident of police misconduct in Baltimore where the key thing to be determined is what was the location of the officer, which is the only thing McNutt’s plane is good for,” Rocah said.

McNutt referenced footage the surveillance plane captured during its 2016 flights—a police shooting, a drug raid—that he believes could be used to police the police and assist citizens, though he did not provide The Appeal with the recordings.

“He’s a salesman,” Rocah said, one who is “playing off of the very real feeling and fears that people have in Baltimore as we watch a dysfunctional police department seemingly fall apart in front of our eyes.”

Oppenheim pointed out that this isn’t the first time surveillance technology has been hawked as a way to keep Baltimore police accountable. In an attempt to address the outcry over Freddie Gray’s death, the city has spent millions on body cameras for officers since 2016.

“Body camera was supposed to be the panacea for misconduct and Fourth Amendment violations and it has done a little of that, but it has been mainly used as evidence against our clients,” Oppenheim said. “The trade off is, it can exonerate a couple people but it’s going to get way more people locked up that shouldn’t be and it’s going to make other cases stronger cases against people who are already overpoliced.”

‘These are paranoid questions’

In 2016, the plane recorded marching protesters specifically because the police were concerned the march might try to disrupt an Orioles baseball game. The ability to monitor protests worries Ralikh Hayes of Black Leadership Organizing for Change, an activist instrumental in organizing marches during the Baltimore Uprising.

“We think this is similar to police body cameras in that it sounds good but when it comes to surveillance technology, it’s all about who controls and stores the data and who has access,” Hayes told The Appeal. “We are heavily opposed because the government doesn’t need more tech to watch Black bodies.”

Dave Maass of the Electronic Frontier Foundation isn’t convinced by McNutt’s reassurances that the images are too low-resolution for individual targeting. He’s concerned about what happens when the image quality improves, when one pixel can easily become 10,000 pixels.

“That’s the technology today—what about in five years?” asked Maass. “Whatever the state of the art is, is not going to be there next year and he will likely forget he made that argument five years in the future.”

McNutt dismissed the technology concern. Even if he increased the quality of the footage 100 times what it is now, he said, he would just be “looking at the top of your head and all I can tell is if you’re middle-aged or balding.”

The argument that the footage is too low quality to be invasive is deceiving, Rocah said, because the plane’s photographs are used with the city’s network of on-the-ground CitiWatch cameras and location data, which makes it possible to identify people in the plane’s footage.

McNutt also shrugged off the general concerns about privacy.

“These are paranoid questions,” McNutt said to The Appeal. “Why would we care about you? How self-centered do you have to be?”

McNutt said he keeps all the footage in “a top-secret safe” that only he can access, and another copy of the video goes directly to the Baltimore Police. After the 2016 flights, neither McNutt nor the police performed an audit exploring the potential for someone else to access and abuse the footage.

Many who voiced privacy concerns in 2016 are not assuaged by McNutt’s promise to use it to keep cops accountable.

“It’s the technological equivalent of every time you walk out of your door, there is a police officer following you,” Rocah said. “And if that happened in real life, we would all viscerally and clearly understand what was going on and find it intolerable.”

‘Our officers don’t tell the truth’

On Oct. 16, Baltimore City Council’s Public Safety Committee held a public hearing on the return of the plane. Williams was in attendance, sitting in the back of the chambers while McNutt walked around handing out a packet labeled “Open Letter to the Leadership of Baltimore.”

“While protections and oversight are in place to limit any potential risk of abuse, we ultimately feel the situation in the city is so dire that the significant benefits of solving unsolvable crimes and deterring crime far outweigh any risks,” the letter, signed by Williams and Joyous Jones, another member of Community With Solutions, argued at one point.

Later it stated: “If the ACLU or others feel this is unacceptable, we would challenge them to come live in our community for awhile then see if they feel the same way.”

But City Council members seemed unmoved by McNutt’s new community-oriented pitch.

City Council Member Brandon Scott, chairperson of the committee, questioned the plane’s usefulness, noting that McNutt had provided investigative briefs for just a little over 100 mainly minor incidents in 2016. He said they were proof the plane had not been particularly effective in solving violent crimes.

“We all know in this body that if you guys were closing homicide after homicide after homicide when this plane was up, the police department would’ve come in with that data ready to go,” Scott said.

Questions from vice chairperson of the committee, Ryan Dorsey, also exposed a new detail about the 2016 flights: Not only was McNutt’s plane recording from above, but his technicians had direct access to CitiWatch.

McNutt and his employees were able to watch high-quality surveillance footage of Baltimore residents up close to coordinate it with the plane footage. Police descriptions in 2016 led residents to believe that McNutt’s technicians had requested CitiWatch footage, not that they had direct access, Oppenheim said.

Council Member Kristerfer Burnett expressed concern that McNutt’s ownership of the video could let him unilaterally sell location data to private clients (something McNutt had mentioned as a possibility in the past) or share footage with federal immigration agents.

Williams made the strongest emotional appeal for the program.

“As you should know, our officers don’t tell the truth. It’s clear. This system tells the truth whether you like it or not,” Williams said. “I just hope that everyone here has an open mind. I understand that the words can get to you—‘spy in the sky,’ it can get to you, but let’s be clear, real people are dying out here in the streets.

When Rocah stood up to testify, he challenged McNutt’s argument that the aerial surveillance program can help stop police misconduct—the argument that converted Williams and others.

“If he’s going around to community leaders and using that as the argument to sell this, it’s really one of the most cynical and repulsive things I have ever heard of anybody doing, ever,” Rocah said. “We have real problems with police misconduct in Baltimore but tracking the location of every resident of Baltimore is [not] going to help.”