Baby’s Death in Mother’s Bed Leads to 5-Year Prison Term. But Was It Her Fault?

An autopsy blamed the sleeping situation, but forensic experts aren’t so sure. And the same Ohio county just charged another mom in a similar case.

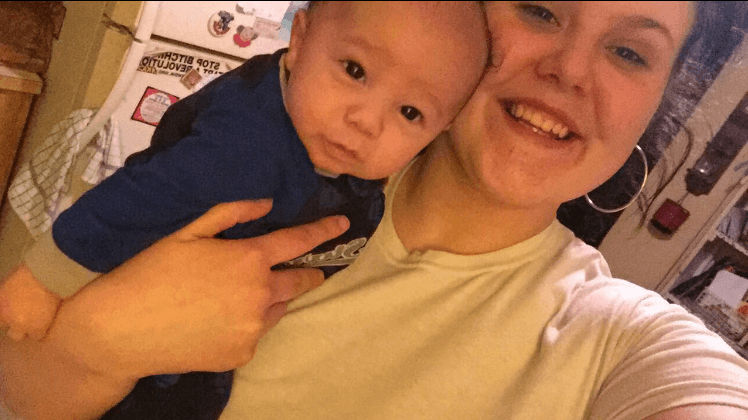

When Addeline Brindle woke up on March 29, 2018, she knew instantly that something was wrong. She had put her 3-month-old baby, Tre’Velle, to sleep in the bed beside her, but now he wasn’t moving. Brindle, 19 at the time, frantically ran around the house where she was visiting two friends, yelling for help. One called 911 and the other, trained in first aid, checked on the baby.

When the ambulance arrived, Brindle didn’t know that she was allowed to go with Tre’Velle, so she didn’t. Mansfield, Ohio, police soon arrived at the house and took her to the hospital. They questioned her at length there, she said, and she told them that she had used cocaine two days before. She didn’t have a lawyer present during the questioning. “I didn’t feel like I did anything wrong, so I didn’t think there was a reason,” she told The Appeal.

Then she was finally allowed to see Tre’Velle, who had been declared dead at 4:50 p.m.

She was distraught, she said, as the police drove her back to her friend’s house in Mansfield, which is roughly halfway between Cleveland and Columbus. They asked her to recreate her sleeping position using a baby doll, standard procedure in infant death investigations. Then they let her go.

But nearly six months later, a police officer came to the pizzeria where she worked, cuffed her, and escorted her out. She was charged with involuntary manslaughter, reckless homicide, endangering children, and possession of cocaine and held in jail on $200,000 bail.

You made some bad choices and you are going to suffer some bad consequences.

Judge Brent Robinson Richland County, Ohio

Her attorney, John Boyd, pushed for probation, noting in court that she had already been punished. “While this is a serious offense, she’s having to endure the most serious consequence of this, which is the loss of her child,” he said during her sentencing.

Judge Brent Robinson wasn’t swayed. “This is what happens when people use drugs,” he said at the time. “You made some bad choices and you are going to suffer some bad consequences.”

But whether Tre’Velle died from Brindle’s choices is far from certain. Medical experts who reviewed the baby’s autopsy report for The Appeal said, based on the autopsy alone, it was unclear whether his death stemmed from his sleeping situation, or from an undiagnosed medical condition. Though infant death investigations have become more thorough in recent years, there are still many babies who die without a clearly identifiable cause. Tre’Velle was one of them.

Yet rather than acknowledge that gray area, the prosecutor and judge used Tre’Velle’s death to send a message about drug use. That’s not uncommon, advocates say.

“The root of it is really very much the deeply ingrained moral judgment of drug use,” said Lisa Sangoi, co-director of the Movement for Family Power, which advocates for the rights of families in the child welfare system. The crackdown on parents—and particularly mothers—who use drugs has intensified during the opioid era, she added. “People will take what should otherwise be a very sad situation,” she said. “The minute there’s evidence of drug use, boom, they drop the hammer.”

The autopsy

Tre’Velle’s autopsy report and death certificate say his death was due to “asphyxia.” Under that designation on the autopsy, it lists “sleeping with an adult,” “sleeping on an adult mattress,” and “pulmonary edema.”

Asphyxia refers to a lack of oxygen in the body, usually caused by a blocked airway or severe chest restriction. According to Brindle, she put Tre’Velle to sleep on a pillow on the opposite side of a full-size bed. When she awoke, she said, he was still face-up, and not wedged against her.

Brindle’s friend, who was renting the apartment, confirmed to police and to The Appeal that she saw them sleeping on opposite sides of the bed. She declined to be named in this story, citing her trauma over Tre’Velle’s death.

Roger Byard is a professor at the University of Adelaide in Australia who has studied infant death and suffocation. He reviewed the autopsy and said he was surprised Brindle had been charged with manslaughter, particularly without any firm evidence that she had rolled onto her son.

“There’s a lot of questions we don’t know the answers to,” he said. “That’s why there’s reasonable doubt.”

Neither Judge Robinson nor Gary Bishop, the prosecuting attorney, returned calls for comment. Tom Stortz, the coroner’s investigator assigned to the case, acknowledged there was no way to know exactly what caused Tre’Velle to stop breathing.

Sometimes smothering would be detectable in an investigation or autopsy, but it wasn’t in this case, Stortz said. Without an alternative explanation, he said, asphyxia was the office’s “best guess” regarding how Tre’Velle died. “Being that the adult was with the child in bed, that’s the most reasonable explanation you can come up with,” he said, noting that an adult can cause such a death without realizing it. “Obviously something happened during the night to cause them not to get any oxygen.”

But even if Brindle had accidentally smothered Tre’Velle, it’s unclear how prison helps, Byard said. “If this woman has, through neglect, caused this child’s death from suffocation, does she need incarceration or does she need treatment?”

“Stepping up to manslaughter is a pretty major step,” he added. “I suppose legally and technically, you can make it this, but I don’t know where the justice is.”

The investigation

The science around infant deaths has evolved in recent years, said Thomas Andrew, a forensic pathologist and former pediatrician who has studied the issue. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, roughly 3,500 babies nationwide “die suddenly and unexpectedly” each year.

In the past, Andrew said, many of those deaths were attributed to Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, a catch-all diagnosis that implied a natural cause when the exact diagnosis wasn’t clear. But in recent decades, thanks to improved investigation of these cases, including the use of doll re-enactments and an updated protocol, forensic pathologists have shifted away from SIDS and toward a recognition that unsafe sleeping conditions could, in some cases, have played a role.

“I think it does reflect a bit more intellectual honesty,” Andrew said, noting that the discovery helped inspire “Safe to Sleep”—which encourages careful attention to a baby’s sleep position and environment—and other public education campaigns.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that babies share a room, but not a bed, with their parents. They should be put to sleep on a firm surface with no loose bedding nearby. Still, a 2016 study by the organization found that 28 percent of newborns, videotaped with their parents’ consent, shared a sleep surface with another person, while a larger study conducted from 1993 to 2010 found that 55 percent of newborns slept with loose bedding. Low-income parents may lack an alternative sleeping space, while other parents simply want to keep their babies close.

There is a subset of these infant deaths that remains beyond our resolution.

Dr. Thomas Andrew forensic pathologist

In some cases, it’s clear from the investigation and autopsy that a sleep environment caused the infant’s death, Andrew explained. But in others, it’s impossible to know for sure. “There is a subset of these infant deaths that remains beyond our resolution,” he said. That has led to more deaths being ruled “undetermined,” meaning they could have happened due to a natural or unnatural cause.

But those types of deaths are labeled differently in different jurisdictions, said Andrew, who is based in New Hampshire and served as the state’s chief medical examiner. By calling Tre’Velle’s death asphyxia, the Richland County coroner implied an unnatural death, but Andrew said other coroners and medical examiners might have been hesitant to make that leap, barring compelling outside information.

“Knowing no more than I know now, in my jurisdiction, this would have more likely than not been certified as an undetermined cause and undetermined manner,” he said. That doesn’t mean the ruling was wrong, he added. “There are no standards on this. … It’s a stylistic variation, but what’s unfortunately missing from the equation is the family on the other end of that diagnosis.”

Andrew and other doctors are working on a book that will include best practices for infant and toddler death investigations and could help standardize the protocol. It is scheduled to be published next month.

The prosecution

Just as there are regional differences in death certification, prosecutors around the country treat such deaths differently and have wide-ranging discretion on when to pursue charges and what charges to pursue. Parents in Florida, Pennsylvania, Utah, Michigan, and Texas have all faced prosecution for bed-sharing. “It’s so simple,” one Indiana prosecutor told a reporter in 2012, announcing a crackdown on the practice. “Don’t sleep with infants and your child is not gonna die.”

The Richland County prosecuting attorney’s office, which charged Brindle, is also taking a hardline approach, as evidenced by Chief Criminal Attorney Brandon Pigg’s statements during her sentencing. “A 3-month-old child has lost his life due to the defendant’s choice to use and abuse cocaine,” he said. “She was responsible for his care and she chose cocaine over that care.”

Implicit in Pigg’s message is the notion that parents, but especially mothers, have a sacred duty to their children, and the justice system should help ensure they fulfill that duty. “There’s no greater bond on earth … [than] parents and children and mothers and children,” he said. “And this was violated here. This was abandoned.”

She was responsible for his care and she chose cocaine over that care.

Brandon Pigg Richland County chief criminal attorney

Last month, Richland County prosecuted another mother. Jamie Haynes, 31, was charged with involuntary manslaughter, reckless homicide, and endangering children in the death of her 14-day-old son, Massiah Taylor.

According to her attorney, Sean Boone, Haynes said she fell asleep on a couch with the baby at 3 a.m. and woke up at 7 a.m. to discover that he had slipped between her and the couch and wasn’t breathing. The coroner’s report concluded that the baby died of positional asphyxiation, Boone said.

The police said Haynes had been drinking alcohol on the night in question; her attorney said there were no illicit drugs involved. Stortz said his office could not share Massiah’s autopsy report because the case is still open.

Haynes, who was recently released on a $5,000 bond, is now facing up to 11 years in prison. “We feel strongly that Jamie is not guilty of these charges,” Boone wrote in an email, “and we fully intend to fight them.”

The family

Brindle was facing a similarly lengthy sentence when she decided to plead guilty, Boyd, her lawyer, explained. He warned her that a jury trial could yield a worse outcome.

But Brindle still doesn’t understand why she was sentenced to five years. Neither does her grandmother Karen Kelley. “Punish her for drugs if you want to get her for whatever, yeah, go ahead,” she said. “Force her to get a job, force her to get her GED, force her to go to some kind of drug counseling, put her on probation.” But putting her in prison doesn’t make sense, she said.

Kelley said Brindle had Tre’Velle’s baby blanket wrapped around her when she walked into Kelley’s house the day he died. Brindle “fell to her knees,” Kelley recalled, and spent the rest of the night crying and vomiting.

After Tre’Velle’s death, Brindle moved in with Kelley, started working at the pizzeria, and attempted to steady her life. She hoped to reunite with her 4-year-old daughter who is living with Brindle’s father’s aunt. Brindle hasn’t seen her in about two years.

“I feel like she’s not going to know who I am by the time I go home,” Brindle said. “She’ll be 9, almost 10, when I go home. I just can’t imagine the person that she’s going to be and the person she’s going to think I am.”

Now in the Ohio Reformatory for Women, a state prison in Marysville, roughly 80 miles from her home in Ashland, Brindle spends her days in GED classes. She said she desperately wishes she could change what happened and that she thinks about Tre’Velle all the time.

“He was amazingly perfect,” Brindle said in one of several 15-minute calls from prison. Like any mother of a newborn, she gushed about Tre’Velle’s facial expressions and how quickly he learned to hold his own bottle. But in another call later that day, her mood had shifted. “So many moms sleep with their kids,” she said quietly. “I didn’t set out for this to happen.”