Why Atlantans Are Pushing to Stop ‘Cop City’

After the city council passed the ground lease for massive police facility known as “Cop City,” local opposition hasn’t ceased; it’s evolved.

This story was produced in partnership with The Mainline, an independent women-led magazine based in Atlanta.

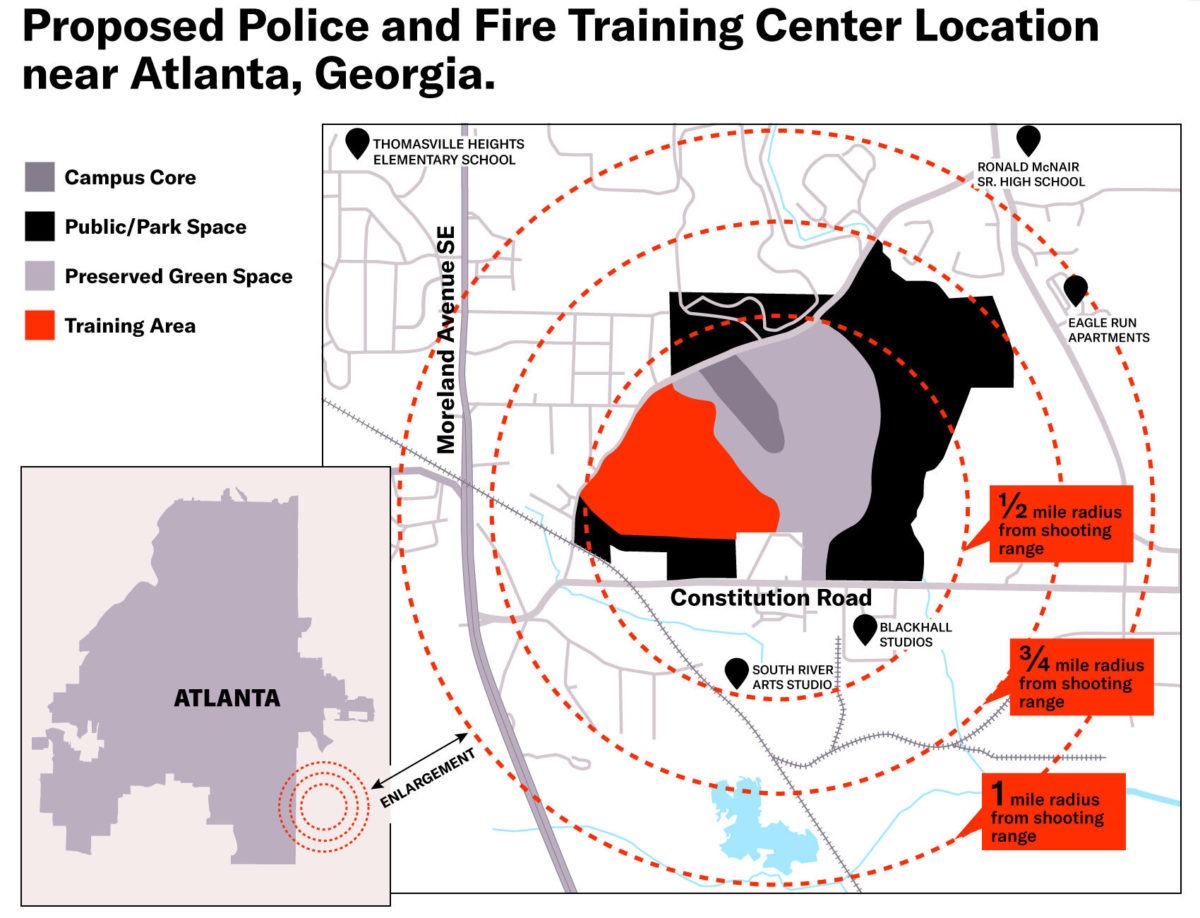

On Sept. 8, the Atlanta City Council gathered after listening to nearly 17 hours of comments from over 1,100 constituents across the city. The flood of messages concerned one thing: a proposed $90 million police militarization training facility known among locals as “Cop City.” The renderings of the facility include a mock city for officers to train in, as well as a helicopter landing base, new shooting ranges, burn tower sites, and more. Its development is being spearheaded by the Atlanta Police Foundation and two-thirds of the funding comes from “philanthropic” and corporate donors, kicking the remainder of the bill to the public.

The project’s supporters, who include Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms and Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp, have described the facility as a vital tool for improving police morale and fighting crime. Yet about 70 percent of the people calling in expressed their opposition to Cop City. Beyond the basic objections to such a major expansion of the city’s policing footprint, environmentalists are also up in arms, since the site’s proposed location lies within the South River Forest, which is the Atlanta area’s largest remaining green space and, scientists say, one of the city’s greatest defenses against worsening climate change.

The land also carries a dark history. Originally inhabited by the Muscogee (Creek) Tribe before their forced removal in the early 19th century, the land became part of a complex of farms that included a slave plantation and federal prison labor site. The area slated to be Cop City was eventually sold to the city of Atlanta, which used it for forced agricultural labor by incarcerated people from 1920 to the late 1980s. (Bottoms has said that the city “didn’t have anything else to choose from” in terms of a site.)

None of these things deterred the City Council. Nor did the 17 hours of comments. After brief deliberation, the council passed legislation to authorize the ground lease of the forested land to the Atlanta Police Foundation in a 10-4 vote. The legislation leased 381 acres of land to the foundation for $10 a year. But there is still a chance that Cop City could be stopped, and people who flooded the City Council meeting with their opposition have vowed to make sure that it is.

The Cop City vote was the culmination of a process that has seen Atlanta’s political establishment — often with the support of the city’s corporate media — relentlessly determined to give Atlanta police what they wanted. This stance is nothing new.

George Floyd’s murder in Minneapolis, along with the police killing of Rayshard Brooks last June, ignited historic protests in Atlanta. But the city’s government has firmly stood in the way of any significant police reform efforts. When the protests began, mass arrests took place throughout the city along with numerous incidents of police brutality, such as that toward college students Messiah Young and Taniyah Pilgrim. The Atlanta Police Foundation paid bonuses to city cops after some staged a sick-out after Officer Garrett Rolfe was charged with felony murder in Brooks’s killing. (Officer Devin Brosnan was charged with aggravated assault after video showed that he kicked Brooks while he was on the ground after being shot.) A City Council member later pushed for additional bonuses to come from the city’s budget. The City Council killed one reform bill at the behest of Bottoms, who then vetoed separate, compromise reform legislation. Officers who were publicly charged in Young’s, Pilgrim’s, and Brooks’s cases have since been hired back on the force and given back pay. The Atlanta Police Department’s budget is now slated at $230 million, a roughly 7 percent increase from the previous year. Now, the city government is working directly with the police foundation to develop its new “state-of-the-art” police militarization facility.

From the beginning, the process to create Cop City has been secretive. Mayor Bottoms quietly ordered the formation of the advisory board for the project on Jan. 4. There was no press release issued and no local coverage. The board consisted solely of police and fire department chiefs, foundation heads, and city employees, seemingly violating the mayor’s administrative order, which said the board should have community members.

Legislation to lease the land for Cop City was introduced in the City Council in June. (Although the land is city-owned, it resides in unincorporated DeKalb County, where residents do not have representation in the City Council.) As public opposition mounted, the police foundation hosted two “public input sessions” over Zoom in July, during which it presented a slide show, answered pre-submitted questions with no time for residents to respond, muted all constituents, and disabled the chat feature. Administrators of the meeting had their cameras turned off and names anonymous.

The police foundation could also count on support from its longtime allies within the city’s corporate and media elite. The editorial board for local legacy newspaper The Atlanta Journal-Constitution vociferously supported Cop City ahead of the vote, and the paper’s “Voices Against Violence” section regularly gave space to pro-police pieces full of tough-on-crime rhetoric that echoed the APF’s talking points. (The paper’s parent company, Cox Enterprises, is a donor to the Atlanta Police Foundation; Cox CEO/President Alex Taylor is leading the fundraising efforts for the facility.)

Ahead of the September vote, it appears the police foundation pulled out all stops. The nonprofit filed as a lobbying group on state and local levels on Aug. 25 with no previous records indicating they had done so in previous years. Nicholas Juliano of local lobbying firm Impact Public Affairs, whose clients include Delta, Uber, and others, is listed as the foundation’s lobbyist with a payment exceeding $10,000.

Over the summer, residents in Atlanta joined in building a widespread coalition in what became known as the “Stop Cop City” campaign. The campaign’s focus was to counter the heavily supportive messaging circulating in the press and from officials, and to push the moderate-to-conservative City Council to oppose the facility. Although the council passed the legislation, the opposition hasn’t stopped; it has evolved. Construction hasn’t yet broken ground and the lease includes a provision that would allow the city to terminate the agreement with the requirement of giving the police foundation 180 days notice. (Atlanta will also be getting a new mayor in January: Andre Dickens, one of the 10 council members to approve the lease legislation.)

Since the vote, organizers have shifted their focus toward connecting with the Muscogee (Creek) community. On Nov. 27, Muscogee (Creek) community leaders from Alabama, Oklahoma, and Georgia gathered in Atlanta to connect with their ancestral lands through a traditional stomp dance ceremony and cultural sharing tradition. The event, which was organized in collaboration with community leaders of the Stop Cop City campaign, took place in the forest at the proposed construction site.

“One of the things that I hope is that this would just be the first step of a migration of our indigenous communities coming back to their homelands,” Rev. Chebon Kernell, of the Native American Comprehensive Plan and Helvpe Ceremonial Grounds, told The Mainline in an interview. “My hope is that together, as we foster this migration back to recognizing our homelands, that also we can educate the public at large, and say, ‘We want a healthier society. We want a safer society for all of our people, especially for our communities of color who have been displaced in so many different ways.’ … We’re hoping that we start with recognizing indigenous peoples, but then we also recognize the intersectionality that takes place with just having the right to exist.”

Organizers have stayed in the streets and kept up their public criticism of Cop City. In a statement ahead of a march on the police foundation’s headquarters on Oct. 23, Community Movement Builders, a local organizing group that has been a core part of the campaign, described the facility as “a war base where police will learn military-like maneuvers to kill Black people and control our bodies and movements,” adding, “they are practicing how to make sure poor and working class people stay in line. So when the police kill us in the streets again, like they did to Rayshard Brooks in 2020, they can control our protests and community response to how they continually murder our people.”

Community leaders in Atlanta have also strengthened their demands for corporate divestment from the Atlanta Police Foundation, which, in addition to Cox, counts among its donors such companies as Delta, Bank of America, and Verizon. The aim is to make police funding an issue not just for governments, but for some of America’s biggest corporations.

“[These corporations] came out with their public campaigns, supporting Black Lives Matter, saying they stand with Black people,” said Kamau Franklin of Community Movement Builders, “but at a moment’s notice, these same corporations … decided to side and build out what is potentially the largest training facility in the country for police to be trained in tactics of suppression. We believe [this] is only for the interest of corporate development and protection of private property, but do nothing for issues of safety and concern for the larger community. So we think targeting these corporations is a really important next step.”

On Oct. 7, Color of Change released a report exploring financial ties between police foundations and corporations across America, identifying connections to at least 55 Fortune 500 companies. The study features 23 cities, including Atlanta, where the police foundation’s actions in relation to the killing of Rayshard Brooks spurred Color of Change to launch the wider study.

After the “Cop City” issue became more well-known, Color of Change became allied with local organizers in their efforts to stop the construction of the facility. Since the vote, Color of Change’s senior director of Criminal Justice and Democracy Campaigns Scott Roberts says their intention is to essentially do more of the same.

“We want to continue to mobilize people and … to try and paint an even clearer picture of what’s wrong here and educate more folks on it,” Roberts explained in an interview with Mainline. “We’re still looking to collaborate with local organizers in terms of both supporting what they think will work, but also to be aligned strategically … I’m pretty sure people are going to continue resisting Cop City even up to the moment where it’s going to try and break ground.”