As New York Decarcerates, The Number of People Under Supervision of Parole Rises

Crime in New York City is at historic lows. The overall number of people in the city’s jails recently dipped below 9,000 for the first time since 1982. Yet the number of people locked up for violating the terms of their parole is on the rise. That is the conclusion of Less is More in New York City, a new […]

Crime in New York City is at historic lows. The overall number of people in the city’s jails recently dipped below 9,000 for the first time since 1982. Yet the number of people locked up for violating the terms of their parole is on the rise.

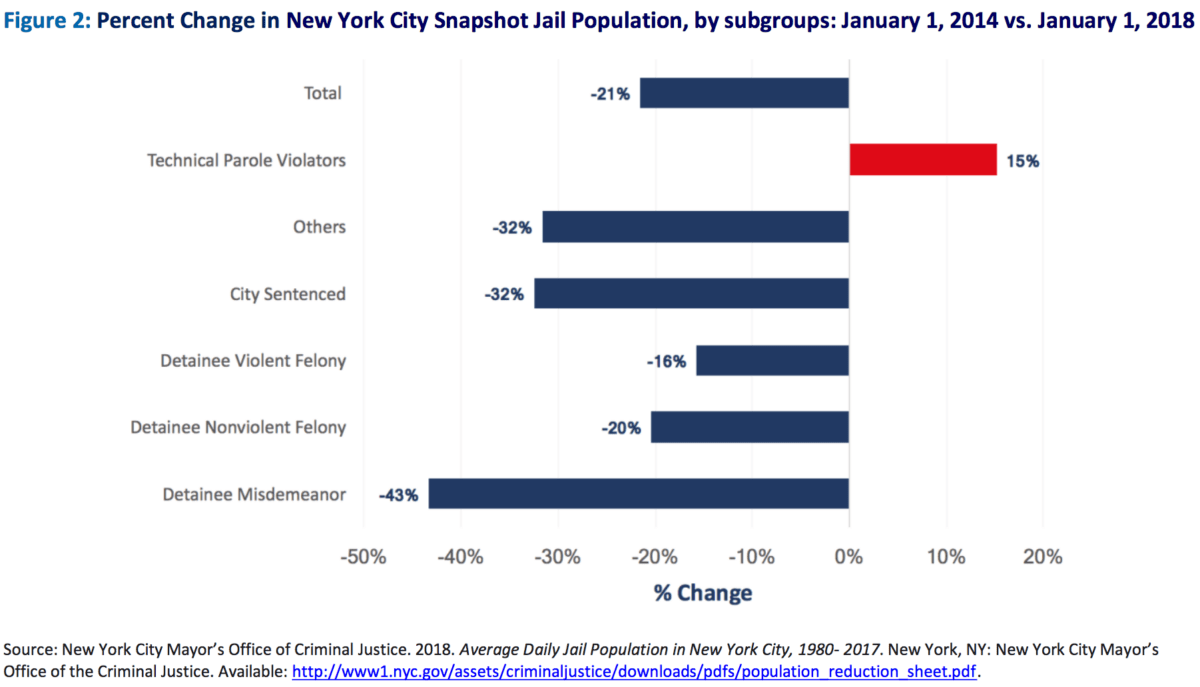

That is the conclusion of Less is More in New York City, a new report from Columbia University’s Justice Lab about the impact of parole violations on prison and jail populations. Since 2014, the number of people in New York City’s jails, including Rikers Island, has dropped 21 percent. But the population locked up for technical parole violations, such as missing an appointment with a parole officer, associating with people with felony records or failing a drug test, has increased 15 percent.

The report takes a snapshot of a single day to illustrate its point: On November 16, 2017, state parole violations made up 16 percent (or 1,460) of people in the city’s jails. Indeed, parole violators are the only part of the New York City jail population that has increased over the past four years.

“In New York, people released on parole are more likely to return to incarceration not for new convictions, but for violating the conditions of their parole,” the report notes.

At the state level, the report reveals, the number of people returned to prison for parole violations increased 21 percent between 2015 and 2016. For every 10 people who successfully completed their parole in New York State, nine were reincarcerated for parole violations. In 2016, those people made up 29 percent of the state’s prison population. But their violations were not necessarily new crimes; instead, nearly half were technical parole violations.

Even New York Governor Andrew Cuomo acknowledged the tremendous impact of parole violations, noting in his 2018 State of the State briefing book that, in 2012, 33 percent of people released from prison were remanded within three years for technical parole violations. “New York jails and prisons should not be filled with people who may have violated the conditions of their parole, but present no danger to our communities,” he stated.

Vincent Schiraldi, the report’s author and a senior research scientist at Columbia University’s Justice Lab, is also a former commissioner of the New York City Department of Probation. He notes that a parole violation generally results in two months in jail while officials hold hearings to determine whether to revoke parole. In other words, people spend an average of two months behind bars waiting to learn whether they will be returned to prison. Schiraldi told In Justice Today that roughly two-thirds end up being sent back to prison; the other one-third are released. But in that time, formerly incarcerated people struggling with reentry can easily lose newly secured jobs or housing.

Author and activist Donna Hylton spent 27 years in prison for kidnapping and murder, followed by five years on parole. She is still in contact with many of the women she was incarcerated with at Bedford Hills Correctional Facility, New York’s women’s maximum-security prison, including those who are now navigating reentry and parole. Two months may be an average, notes Hylton, but she knows of cases in which the jail time stretched even longer. She recounted working with a young woman whose parole violation stemmed from her drug addiction. “She spent almost nine months waiting for a hearing,” Hylton said. Though the woman was ultimately not remanded to prison, those nine months behind bars resulted in her child being placed in foster care. “She’s now trying to put her family back together, put her life together,” Hylton said, “Incarceration and re-incarceration should not be the response to addiction. A lot of technical violations are because of that.”

Vonda Seward, the former statewide director for reentry services for the New York State Division of Parole, agrees. “When we talk about technical violations, most of them are drug-related,” she told In Justice Today. “Going to jail or prison is not the answer to getting high.” But, she noted, parole officers err on the side of caution to avoid risking a future crime. “When you work for parole, you’re only as good as your last successful case.”

“Incarceration and re-incarceration should not be the response to addiction. A lot of technical violations are because of that.”

At the same time, both Schiraldi and Seward note, parole officers have limited ability to help with the plethora of parolees’ pressing needs, such as housing, employment and health care. But that doesn’t mean they won’t threaten parolees with violations for not finding resources on their own.

That’s what happened to Donna Hylton. In January 2012, with her parole officer’s initial approval, Hylton left a transitional program to reconnect with family. When she realized that her family’s home was still unhealthy and that she could not stay with them, she was left without housing. Her parole officer told her that unless she found a homeless shelter or a residence that the parole officer approved, she would be sent back to prison. Fortunately, Sister Mary Nearney, a Roman Catholic nun and founder of numerous programs for incarcerated women, whom Hylton had met while in prison, came to her rescue. In February 2012, Hylton moved in with Sister Nearney until she was able to find her own apartment. “I was an exception,” she notes. “So many other people don’t have that.”

Lack of housing is a common barrier for people returning home from prison, and for those on parole, it can easily become a pathway back to prison. That’s something Topeka Sam, director of the Ladies of Hope Ministries, a faith-based reentry program for women, learned firsthand after establishing Hope House, a transitional home for formerly incarcerated women in the Bronx.

In the fall of 2017, she was prepared to accept the house’s first residents — five women scheduled to be released on parole from the New York state prison system. But then the Department of Corrections and Community Supervision (DOCCS), which operates the state’s prison and parole systems, refused to approve Hope House because Sam herself is formerly incarcerated and currently on federal probation (though her probation officer approved her efforts to create Hope House). Sam told In Justice Today that most of the women whom she is now unable to house went to shelters; one woman remains in prison for lack of approved housing.

The Justice Lab report offers several policy recommendations for decreasing the number of people jailed for parole or probation violations, including shortening parole terms, requiring a hearing before jailing someone for a technical violation, creating a high legal threshold for jailing people for less serious parole violations, and using graduated sanctions and rewards rather than the threat of immediate incarceration.

But, Seward said, these recommendations won’t happen without pressure from Governor Cuomo. “We can continue to show reports and data,” she said, “but if the governor doesn’t put his foot down on what he wants, it’s not going to get done.”

Correction: This story has been edited to note that only the number of people violating the terms of parole, not probation, is on the rise.