As Bail Reform Moves Forward in California, Defendant Who Advanced It Remains Incarcerated

In California, as elsewhere in the nation, there’s a growing consensus that cash bail unfairly penalizes poor defendants, forcing them to sit in jail for months or even years pre-trial, while wealthier defendants walk free. Last year, California nearly ended cash bail after a bill, SB 10, passed the State Senate and then stalled out in […]

In California, as elsewhere in the nation, there’s a growing consensus that cash bail unfairly penalizes poor defendants, forcing them to sit in jail for months or even years pre-trial, while wealthier defendants walk free.

Last year, California nearly ended cash bail after a bill, SB 10, passed the State Senate and then stalled out in the Assembly over cost concerns this past summer. As the state’s legislative season began anew in January, legislators were determined to enact SB 10, buoyed by the state’s Chief Justice Tani Cantil-Sakauye recommending that cash bail be eliminated as soon as possible in a report released last fall.

In late January, meanwhile, a state appeals court ruled that defendants are entitled to hearings to determine their ability to pay their bail; if they cannot afford it, they must be offered alternative forms of bail, such as electronic monitoring and community supervision.

The decision centered on a San Francisco retiree, Kenneth Humphrey, who allegedly stole $5 and a bottle of cologne and was held on $350,000 bail. It became judicial precedent statewide on February 20, when California’s Attorney General Xavier Becerra declined to appeal to the state’s supreme court, announcing, “It’s time for bail reform now.”

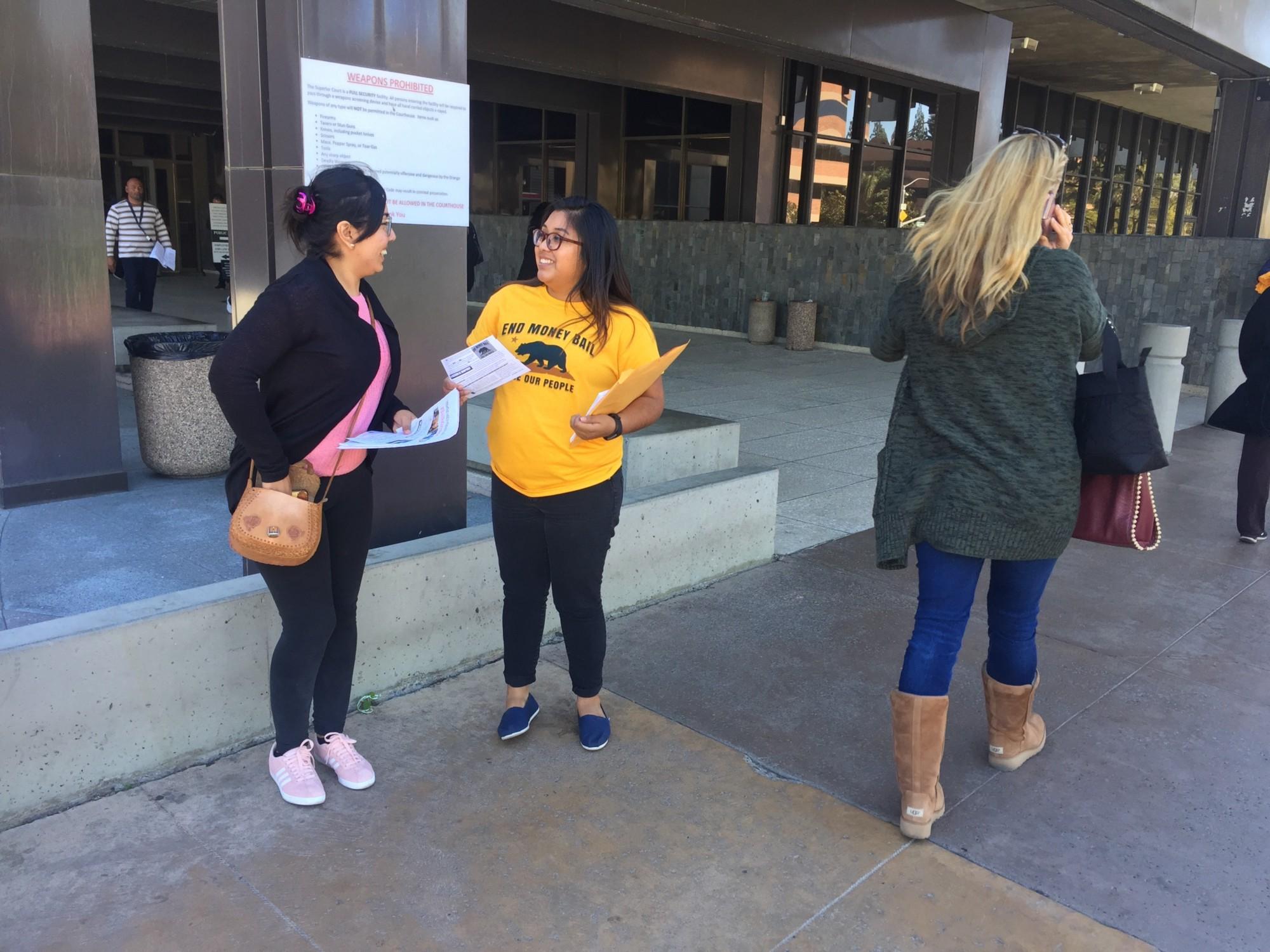

On the day of Becerra’s announcement, Dulce Saavedra, a 24-year-old organizer with the youth organizing group Resilience OC, stood in front of the Orange County courthouse in Santa Ana, handing out flyers informing potential defendants and defense attorneys of their rights following the Humphrey decision. It was part of a day of action by reform groups across the state, who held simultaneous rallies and handed out flyers outside nine county courthouses.

“There’s no standardization when it comes to bail here,” Saavedra, told The Appeal. “You can get no bail set, or you can have your house, your mortgage, your whole life taken from you.” She stressed the need to not only eliminate cash bail, but to make sure it isn’t replaced with tools that may discriminate against people of color, like risk assessments, which attempt to predict how likely a defendant is to commit a new crime or fail to return to court. “Risk assessments are based on really racist criteria,” Saavedra said, “like … how much money do you make? do you have a home? do you own a home?”

As the end of cash bail in California draws nearer, Raj Jayadev, founder of Silicon Valley De-Bug, a community organizing and advocacy group based out of San José, which helped organize the statewide rallies last Tuesday, stressed that it’s up to community groups and advocates like Saavedra to push for the changes they want.

“We finally got to a place where this might happen,” Jayadev said, “and if we blow it now, if we get stuck with a bill that doesn’t reflect what we’ve been pushing for this entire time, then what was it all for? It’s going to be people in the courthouses holding prosecutors and judges accountable that make change happen, making sure they follow through, because they’re not just going to do it themselves.”

So advocates who had been flyering outside the Orange County courthouse sat in on the afternoon’s criminal arraignments, using surveys that had been distributed statewide to write down bail amounts that were being offered and to see if defense attorneys were requesting bail hearings (both criminal cases that afternoon were dismissed).

In places like Orange County, where the prosecutor’s office has a long history of misconduct, court-watching and community accountability are all the more important.

“In Orange County, the DAs tend to feel like they can get away with anything,” said Ramon Campos, another organizer with Resilience OC. “From things like having snitches inside facilities to re-writing risk assessments where they can change what’s on that report and push for higher punishment for that person.”

In a state where over 60 percent of those detained in jail are being held pre-trial, ending cash bail would mean a seismic change in the criminal justice system, one that community groups and advocates feel they need to keep a close eye on.

“The community education part is really important,” says Campos. “If the attorney fails to ask for a hearing, the community can push them to do it. That knowledge just builds more and more power.”

Public defenders and advocates are already hitting resistance. Last Thursday, Kenneth Humphrey appeared in court to move forward with his own bail hearing. His San Francisco public defenders had arranged for a bed in senior housing and transportation, on the assumption that after the appeals court decision, he would receive another bail hearing and possibly be released.

But San Francisco District Attorney George Gascón’s office argued that the case had not yet been sent back down from the higher court, and the judge could not yet hold a bail hearing, even though other defendants in San Francisco had already been granted theirs. Humphrey, whose case sets a precedent that is already freeing people across the state, currently remains in jail.

“Everybody else in the state of California can now get a new bail hearing because of the Humphrey decision, and Mr. Humphrey himself cannot,” said Chesa Boudin, a deputy public defender in San Francisco who worked on Humphrey’s case with Civil Rights Corps, a nonprofit group that challenges systemic injustice in the American legal system. “The court of appeal and the state of California agree that Mr. Humphrey has been held in violation of his constitutional rights for over 275 days. And now the district attorney says no based on a technicality? They want him to wait another month before he gets the bail hearing that complies with minimum constitutional standards? It’s an outrage.”

The Humphrey decision may set the precedent for bail hearings, but it also shows how district attorneys, even supposed “reformer” DAs like Gascón, will throw up roadblocks between people who have not been convicted of crimes and their freedom. Gascón’s office has a history of setting bail for defendants even after risk assessment tools have recommended their release.

No date has been set for a bail hearing, according to Humphrey’s defense attorneys. In an email to The Appeal, Gascón’s office said the decision to delay Humphrey’s bail hearing was made by the court, and not at the urging of the DA’s office.

If passed this session, Senate Bill 10 would still not go into effect until 2020 at the earliest, meaning that for thousands of arrested individuals, the Humphrey decision could, for now, mean the difference between keeping their jobs and their homes, or languishing in jail simply because they don’t have the money to pay their bail. Groups like Resilience OC and others that rallied across the state see it as their duty to hold all of the actors in the criminal justice system, including Gascón, accountable for a radical change to the state’s bail policy.

“We need to be an everyday presence in the courtrooms,” says Jayadev. “We need judges spending the days before the bail hearings considering just what they’re doing to defendants when they set bail, and the impact it has on the communities they serve.”