Anti-Backpage Law Not Yet Enacted, But the Crackdown on Sex Workers Has Already Begun

On Friday, April 6, the same day that Congress sent FOSTA — the Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act — to President Donald Trump for his signature, the Department of Justice seized Backpage.com, the website FOSTA was meant to take down. After weeks of arguments about why this legislation was necessary […]

On Friday, April 6, the same day that Congress sent FOSTA — the Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act — to President Donald Trump for his signature, the Department of Justice seized Backpage.com, the website FOSTA was meant to take down. After weeks of arguments about why this legislation was necessary to attack sites hosting sex work ads, it turned out the government could target Backpage without it.

Before the Senate had finished its vote on FOSTA on March 21, its co-sponsors gathered for a press conference, livestreamed by the Senate GOP. “We had a big victory,” began Senator Rob Portman (R-OH). “We now have the ability to go after these websites that are exploiting women and children online.” A few minutes later, an adult model named Brie Taylor said she was trying to access Cityvibe.com, a website that hosted sex work-related ads. “I was flagging an ad with my pics in it,” she tweeted, “…and then the site was gone.”

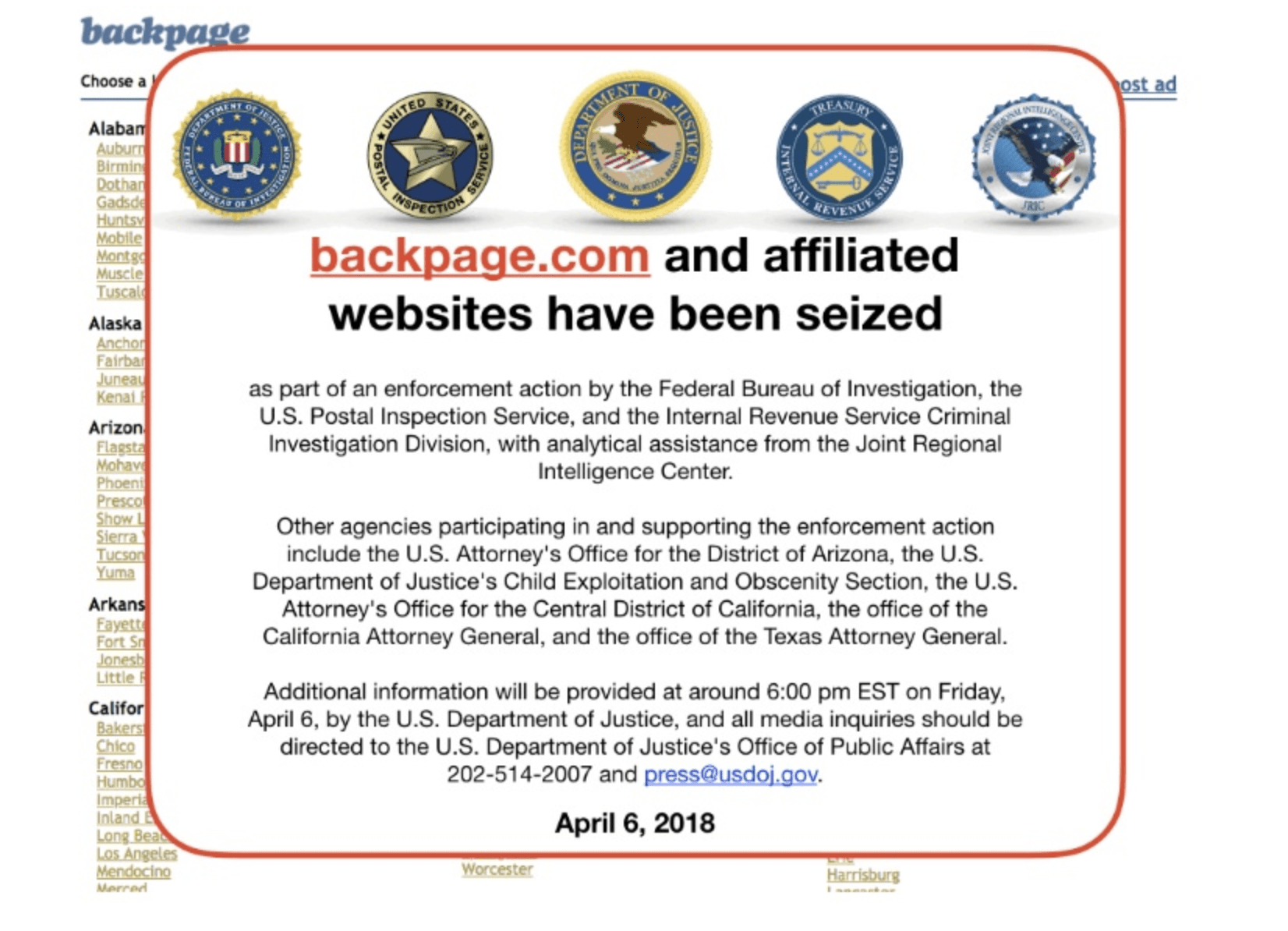

That advertising site is still offline — along with Craigslist’s entire Personals section, and the ad sections of several lesser-known websites. But the big news came Friday afternoon, when Backpage had its homepage replaced with a notice stating, “Backpage.com and affiliated websites have been seized as part of enforcement action by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the U.S. Postal Inspection Service, and the Internal Revenue Service Criminal Investigation Division.”

Groups that had long been mobilizing against Backpage, like the anti-sex work lobby group Coalition Against Trafficking in Women (CATW) and the religious right group National Center on Sexual Exploitation (NCOSE) have celebrated the takedowns. FOSTA is not yet in effect, but in demanding the law, its supporters have already created a political environment more favorable to such law enforcement actions.

FOSTA, as advocates warned, offered a symbolic win against Backpage that went beyond a legislative victory for people who have been trafficked. “It seems to me that a lot of FOSTA’s supporters simply want Backpage to be unprotected, period,” Alexandra Levy, adjunct professor of law at Notre Dame Law School, where she teaches about human trafficking, told The Appeal. “And FOSTA is indeed necessary if that’s your goal.”

At least one of FOSTA’s authors acknowledged that link explicitly. Though the bill is not yet signed, Representative Mimi Walters (R-CA) tweeted Friday, “Thanks to #FOSTA with my #SESTA Amendment, the Department of Justice has seized backpage.com and affiliated websites that have knowingly facilitated the sale of underage minors for commercial sex.”

Supporters of the legislation pitched FOSTA, along with the original bill that inspired it, SESTA (the Stop Enabling Sex Trafficking Act), as a tool to fight trafficking by making it easier for victims to file civil suits. Backpage’s alleged involvement in trafficking was also the subject of a 2017 Senate investigation, which sparked this legislation. But despite claims about the site, the seven Backpage owners and staff named in this week’s indictment have not been charged with trafficking. Rather, they face the same charges — money laundering, violation of the Travel Act for facilitating prostitution — already used against the sex work sites Rentboy.com and MyRedbook.com in recent years.

By the time FOSTA came to a Senate vote in March, the tech companies that opposed it on free speech grounds had largely backed off. The remaining opposition came from those who stood to lose the most from the legislation: sex workers themselves. The disappearance of ad sites like Backpage is what sex workers’ rights advocates had feared. They argued that the sites helped them stay safe by allowing them to screen clients and avoid more dangerous situations — a form of harm reduction, as they described it — though those concerns went unheard in Congress. Now “people are angry, terrified and panicked,” Lola, a community organizer with Survivors Against SESTA, a newly formed campaign for sex worker rights’ advocates, told The Appeal.

Since the Senate vote, the group has collected reports from sex workers about websites that have shut down or changed their terms of service so as to exclude sex workers. “Some of the content that’s getting removed is livelihood-related,” she said. “Some of the content is activism-related.” At the same time, the anti-Backpage group NCOSE is keeping its own tally of site takedowns, celebrating them on Twitter. A CATW policy adviser and former staffer in the State Department’s Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons tweeted “#SESTA impact” and an image of a 2009 Israeli air force bombing of Gaza.

As these groups claim victory for FOSTA’s passage — and still fundraise based on it — much about the actual enforcement of FOSTA remains uncertain. What is clear is that the ad platforms sex workers rely on for income are going offline. And that leaves sex workers desperately trying to figure out how to respond — and how to survive.

FOSTA, the bill that passed both the House and Senate, is expected to be signed by Trump. (The bill known as SESTA is essentially dead, though elements of it were included in FOSTA.) FOSTA amends both the Mann Act, a 1910 law concerning what was called at the time “white slavery,” and the Communications Act, to allow state attorneys general and victims of trafficking to take legal action against website operators for “the intent to promote or facilitate the prostitution of another person.”

“Facilitating” prostitution, however, could cover a very broad set of activities. SESTA co-sponsor Senator Richard Blumenthal (D-CT), in a floor speech before the Senate vote in March, said the legislation before them “would not criminalize so-called ‘harm reduction’ communication.” But that’s far from a guarantee, critics say, since we don’t know how prosecutors might try to make these “facilitating” cases. There’s also no guarantee a site sex workers use to exchange “bad date” lists or other health and safety information couldn’t also be exploited by traffickers and thus be vulnerable to lawsuits.

In the weeks after the FOSTA vote but before the law has gone into effect, two cases against Backpage advanced in courts in Massachusetts and in Florida. Ironically, these are the kinds of lawsuits, charging Backpage with trafficking, that FOSTA’s supporters said would be impossible without changing the law. The Massachusetts case may provide a glimpse into the legal problem FOSTA was supposed to solve. In that case, a judge ruled that since one plaintiff showed evidence Backpage had altered an ad she was featured in, her case against the company could proceed.

“This result shows that even the slightest bit of evidence that Backpage creates ads for trafficking victims will allow those victims to have their day in court,” said Levy of Notre Dame Law School. The existing law targeted by FOSTA, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, said Levy, “doesn’t offer protection to any traffickers, including websites, and this case demonstrates that fact.”

While it’s impossible to predict how FOSTA will be enforced, said Levy, “it doesn’t even matter that much, because uncertainty does most of the heavy lifting when it comes to chilling speech. Nothing is as destabilizing as confusion in this context…. no one can honestly assure people that they won’t be on the hook.”

Backpage was a clear target, but before it was taken offline, more than a dozen other ad platforms had been taken down by their owners since the Senate vote on March 21. All of this is contributing to the panic sex workers are reporting. These takedowns are about how different owners of different sites and platforms interpret a law that has yet to be enforced, and many of those owners are making those calls without notice.

The same week as the Senate vote, some sex workers began reporting that their content was vanishing from Google Drive — not only content related to doing sex work, but educational materials intended for the general public. “The actions tech platforms have taken on individual accounts can be so isolating — they’re hard to prove,” Lola from Survivors Against SESTA said. “They come without warning. Sites like Google are denying that they’re SESTA/FOSTA-related.” (A Google spokesperson told The Guardian in March, “Google is aware of the new legislation and we are reviewing it, but we haven’t reached a state where there are any proposed changes.”)

At least one site made an effort to communicate its new content rules, which provides an indication of how site owners are making these decisions. Alex Empire, a sex worker who moderates the r/SexWorkers subreddit, said she received a message from Reddit advising her that “any posts that could facilitate the connection of sex sellers and sex buyers would be a violation.” Empire briefly closed the group to the public, but it is active again, featuring discussions like “New podcast episode about sex work, stigma, and the State” and “6 Sex Workers Explain How Sharing Client Lists Saves Lives.” But that’s not the norm, said Lola, when it comes most of the takedowns she and other advocates have seen.

The consequence is that sex workers are left to fend for themselves. For some of the sex workers interviewed by The Appeal, that has meant scrubbing any mention of sex work from their online profiles; for others, it’s meant deleting much of their web history altogether. Some have opted to use platforms hosted outside the United States.

But even that is no guarantee. Elliot Harmon, activist at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, said taking content outside the U.S. isn’t necessarily a solution. “If I operate a message board that puts me at risk of prosecution under SESTA/FOSTA and I move that message board to a hosting platform outside of the U.S., I may still be at risk,” Harmon said. Right now, he added, there are no easy answers. “Be leery of anyone claiming to have a solution for everyone,” Harmon said. “Talk to a lawyer.”

Kate D’Adamo, a partner with Reframe Health and Justice, was one of the advocates who predicted the current fallout. “I didn’t want to be right,” she told The Appeal this week. As the bills moved closer to a vote, D’Adamo and other sex worker rights advocates sounded the alarm. “I had moments of feeling like Chicken Little over and over,” she said. “Lawyers who supported the bill, like Mary Mazzio [director of anti-Backpage documentary I Am Jane Doe], and tech advocates opposing it kept telling me I was wrong and wouldn’t budge.”

D’Adamo continued, “But that’s the same social gaslighting that makes legislation like this, which says you can just pull yourself out of chronic, generational poverty if you work hard enough or only people with something to hide avoid police.” FOSTA claims to be anti-trafficking legislation, but it doesn’t attack trafficking, she added. It attacks websites, and those who use them.

With or without Backpage — or FOSTA — sex workers aren’t going offline. “Sex workers will know how to survive this,” D’Adamo said. “But sex workers also know that it’s going to hurt for a while and we’ll lose folks along the way.”