How a Group Policing Model Is Criminalizing Whole Communities

This article was published in collaboration with The Nation. Editor’s note: After publication, The Appal received letters from David Kennedy and other proponents of the Ceasefire model that challenged this article’s characterization of the model and its effectiveness. An internal review determined that the story contained a number of inaccuracies related to the BRAVE program and the description of […]

This article was published in collaboration with The Nation.

Editor’s note: After publication, The Appal received letters from David Kennedy and other proponents of the Ceasefire model that challenged this article’s characterization of the model and its effectiveness. An internal review determined that the story contained a number of inaccuracies related to the BRAVE program and the description of Kennedy’s model, which we have corrected in the text as well as in the headline and sub-headline of the story. More significantly, the piece inaccurately identified New York City’s Operation Crew Cut as a Ceasefire program; it is not, and Kennedy has no relationship with it or the gang indictments that it has produced. We have removed the paragraph which made those claims, as well as quotes that contained comment on other non-Ceasefire programs. The story also overreached in contending that evidence has definitively shown that Ceasefire does not work; in fact, while research is inconclusive on whether reductions in violence can be sustained, cities that have implemented the model do usually find at least a short-term drop in violence. Finally, we failed to contact Kennedy for comment, which represents a serious lapse in our process. We deeply regret these errors.

Shortly after Democrat Sharon Weston Broome became mayor of Baton Rouge last January, her office was informed that the Justice Department was freezing payments and possibly canceling a grant that had allocated to the city over $3 million during the past five years to help reduce violent crime in Baton Rouge. The Department of Justice cited missed reports from the previous mayoral administration, as well as a lack of use of social services — one of the requirements of the grant.

The grant had been funding an initiative known as Baton Rouge Area Violence Elimination (BRAVE), which used data-driven models to identify youths at risk of committing violence and, through a combination of deterrence and social services, allow them an exit from possible criminal activity. Another part of the grant was designated for violent crime research and data analysis by a team at Louisiana State University, including the development of a database that could be used by police to identify subjects for the BRAVE program. Broome had run on police reform, and her new administration quickly came up with a plan to salvage the program, but it was too late. In June, the Department of Justice declined to renew the grant. Still, it allowed Broome to spend the remaining $1.7 million of the unspent funds on the social services for which they were originally intended.

Broome’s office began quickly distributing the funds to local service providers, focusing on mentorship programs, arts camps, and job-readiness trainings, many of which had been included in the original grant proposal. One of those grants was given to Arthur “Silky Slim” Reed, a prominent member of the community who had been integral to the weeks-long protests that sprang up following the police killing of Alton Sterling the summer before. Reed was awarded a contract to offer counseling services to teens identified as being the most at risk of committing violence. A few weeks later, however, Reed became embroiled in controversy after remarks at a Metro Council meeting where, furious that the officers who killed Sterling have not been prosecuted, he declared the recent shooting of six Baton Rouge police officers a form of justice.

“The fact that our federal tax dollars have gone to someone like Arthur ‘Silky Slim’ Reed is downright repulsive,” said Louisiana Republican Senator John Kennedy after Reed’s comments. (In fact, though Reed was awarded the contract, it was canceled before the funds ever changed hands.) Following Kennedy’s lead, some on the right took aim at Weston Broome, a black woman, for putting Reed on the project’s payroll, while questioning why money from the Justice department was being spent on social services at all and not on law enforcement. At the end of September, when the grant ended, just under a million dollars were left unspent.

As the program collapsed, another defender stepped in: East Baton Rouge District Attorney Hillar Moore, one of BRAVE’s architects. There was no reason that BRAVE should be scrapped just because contracts had been misallocated, he argued. Moore’s office was benefiting from the less controversial part of the grant: research tools that could be used by police and prosecutors. BRAVE’s federal funding, which began in September 2012, specifically provided the district attorney’s office and the Baton Rouge Police Department with the capacity to pursue data-driven gang policing. For Moore, the grants had worked wonders in helping his office bring large gang indictments.

The combination of gang policing and social-service funding that characterized BRAVE, at least on paper, reflected its origins in a criminology theory called focused deterrence, often referred to as “Ceasefire.” (Ceasefire’s authors have moved away from the term “gang” and now prefer the word “group,” arguing that not all violent groups can be classified as gangs; the word “gang” does appear in Ceasefire materials, including its official implementation guide.) Ceasefire has been marketed as a more humane and precise form of law enforcement, but is now being used to hold large groups of people responsible for the conduct of a few. The result is a program that sounds progressive on its face, but has been used repeatedly in a form that emphasizes on its most potentially punitive aspects. The collapse of BRAVE reveals not just a program in turmoil but a theory that may be far less progressive than it seems.

“Operation Ceasefire,” also known simply as “Ceasefire,” was developed by a criminologist named David Kennedy in the 1990s. According to Kennedy, because crime “does not occur evenly” across a city, neither should policing. The first part of Kennedy’s model involves mapping out crime data, encouraging police to focus on violent parts of every city — in effect, almost always low-income communities of color. The theory went that, to help reduce gun violence in these mapped areas, police would reach out directly to groups of individuals considered “at risk” and offer to connect them to social services to encourage a move away from committing crimes that could lead to incarceration. These services were offered at a “call-in,” sometimes held in a police precinct, with cops and prosecutors warning individuals that they were being watched by police closely, and that if they were to commit a violent crime, they would be subject to enhanced sanctions and enforcement action. Surveillance was part of the theory: police identified groups based on information they had gathered from past arrests and incidents, on-the-street observation, and social media; those groups were then the target of police attention, and suspected group members were often added to a database.

Following the program’s introduction in Boston, Ceasefire was implemented nationally in cities ranging from Kansas City to New Orleans and, beginning in 2012, Baton Rouge. Many cities gave Kennedy’s model a different name — in Kansas City, it goes by “No Violence Alliance”; in New Orleans, “NOLA For Life”; and in Baton Rouge, it was “BRAVE.” In each iteration, Kennedy advised the programs from his research center at John Jay College in New York. Hailed by both the Bush and Obama Justice Departments, Kennedy has become the most celebrated criminologist in America, with a book called Don’t Shoot: One Man, A Street Fellowship, and the End of Violence in Inner-City America published in 2011 that earned blurbs from both former New York police commissioner Bill Bratton and pop-sociologist Malcolm Gladwell. Kennedy has repeatedly been hailed by reporters as the mind behind a sort of “Moneyball” for policing, in which large amounts of data reveal those most likely to violently offend.

But Kennedy’s model isn’t the clear success that its adherents claim it to be. While many cities see sharp drops in crime during the initial months of Ceasefire’s implementation, it’s less clear whether those drops can be sustained in the long-term. There’s little research on the focused deterrence model’s long-term impact on violence, and the research that does exist is mixed. And the model’s reliance on collective punishment risks incarcerating large numbers of young people, despite Kennedy’s claims that his method focuses on deterrence and mobilizing communities against violence. In his memoir, Kennedy blames the programs’ failings on inadequate funding and inconsistent implementation. A part of the model that typically appears to function, however, are the indictments. In New Orleans, at least 106 people were indicted for gang activity during its Ceasefire program. In Oakland, over a hundred people have been arrested as part of its Ceasefire program.

In 2011, Moore, the East Baton Rouge District Attorney, began looking for ways to cut down on a trend of increasing homicides in the city stretching back to 2005. Like DAs before him, he turned to the Operation Ceasefire model, taking on Kennedy as a consultant and applying for a grant from the Department of Justice’s Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, which has funded Kennedy’s model for years. Over four years, Baton Rouge received over $3 million from the DOJ to try to reduce violence in two ZIP Codes — 70802 and 70805. But the city never spent just under $1 million of the $3 million in grants it received, and over the program’s course only 65 youths benefited from it through BRAVE-funded social services — less than half the number the city proposed in the grant application.

“I don’t think this represents the highest-risk kids,” says Stephanie Kollmann, the policy director at the Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law’s Children and Family Justice Center, who examined BRAVE’s four annual reports compiled by Louisiana State University. “How are these kids being identified? Because self-identification doesn’t get you your hardest-to-reach kids. Just because they’re from the right ZIP Codes doesn’t mean they’re the ones they should be talking to.”

According to Louisiana State University’s annual reports for 2013 through 2016, the most popular social service provided to participants was transportation assistance, with 24 people served between 2013 and 2014, 28 served in 2015, and 25 in 2016. In its last year, only two people completed mental-health treatment, and only two people were offered substance-abuse treatment. For service providers, the buy-in to the program was clear — millions of dollars from the federal government would be distributed to organizations hit hard by budget cuts under eight years of austerity by then–Governor Bobby Jindal.

Another way that young people were targeted for participation in the program was through their inclusion in a database. About half of the spent money from the grant went to LSU, for the database the research institution had designed and was now operating, capable of completing “social-network analyses” of suspects.

“The degree of involvement in criminal activities is not usually a factor of inclusion in these databases,” Kollmann says, pointing out that inclusion in a database generally long outlasts criminal involvement, “because there’s no clear guidelines as to how someone gets put into the database. Young people’s involvement in active gang status is a very brief period, maybe two to three years at most. Putting them in a database guarantees lifelong law-enforcement attention, however.”

Ceasefire’s emphasis on mapping and targeting specific groups is part of a larger trend toward data-driven policing in police departments across the country, with cops increasingly surveilling low-income neighborhoods for information about gang affiliations. Their surveillance isn’t high-tech — it mostly takes the form of looking at the social-media accounts of individuals, or by taking photos of individuals during stops on the street and marking down what colors they were wearing, and if they have tattoos. Ceasefire uses a combination of street-based intelligence and reliance on existing criminal justice data sources such as parole, arrest, and probation records.

Once someone has been identified as being at risk, the social-services side of Ceasefire should kick in, but that rarely happens, Kollmann observes. “What motivation would they have to do anything besides what they’re trained to do, which is arrest and prosecute?”

Andrew Ferguson, a professor at the David A. Clarke School of Law in Washington, DC, has studied the growing use of data-driven policing throughout the country and has published a book, The Rise of Big Data Policing: Surveillance, Race, and the Future of Law Enforcement. To him, this presents a fundamental problem to the Ceasefire model.

“One of the problems with predictive policing is that there’s policing involved,” Ferguson explains. “The predictive analytics of trying to identify who might be involved in crimes is good, but why would the answer have to be police? There’s this weird conflict where police and prosecutors are the people who are supposed to be intervening and warning people to go on the right path. But that’s completely contrary to their role…. If they’ve convinced themselves someone is a real danger to the community, they’re not going to be selling the importance of social services the way they would be if they were a social worker or a member of the community.”

Within its first full year of operation in 2013, BRAVE claimed it had contributed to a sharp drop in homicides, from 83 in 2012, to 66 in 2013. The assumption that a single program can take credit for a drop in homicides in a single year is something that criminologists often warn against. Year-over-year stats are notoriously unreliable and considered “noisy” by statisticians. Homicides in East Baton Rouge Parish declined even further to 63 in 2014, but then shot back up to 78 in 2015.

And Fordham law professor John Pfaff, author of Locked In: The True Causes of Mass Incarceration — and How to Achieve Real Reform, warns that BRAVE’s focus on two ZIP Codes alone is “troubling.” “The way they report the data seems likely to overstate BRAVE’s impact,” Pfaff told me, pointing out that the parish as a whole was experiencing a drop in crime, even though BRAVE only focused on those two zip codes. Most “Ceasefire” iterations operate without a control group (such as a similarly violent area without enhanced policing for the model to be compared to), and BRAVE was no exception. This makes it that much harder to actually prove it had a discernible impact. “The way they keep looking at 70802–5 [the two ZIP codes chosen] in isolation,” Pfaff continued, “not comparatively with the control group, is troubling. Not sure it’s intentional, but it makes it really hard to separate out the effect of BRAVE from whatever else was happening.”

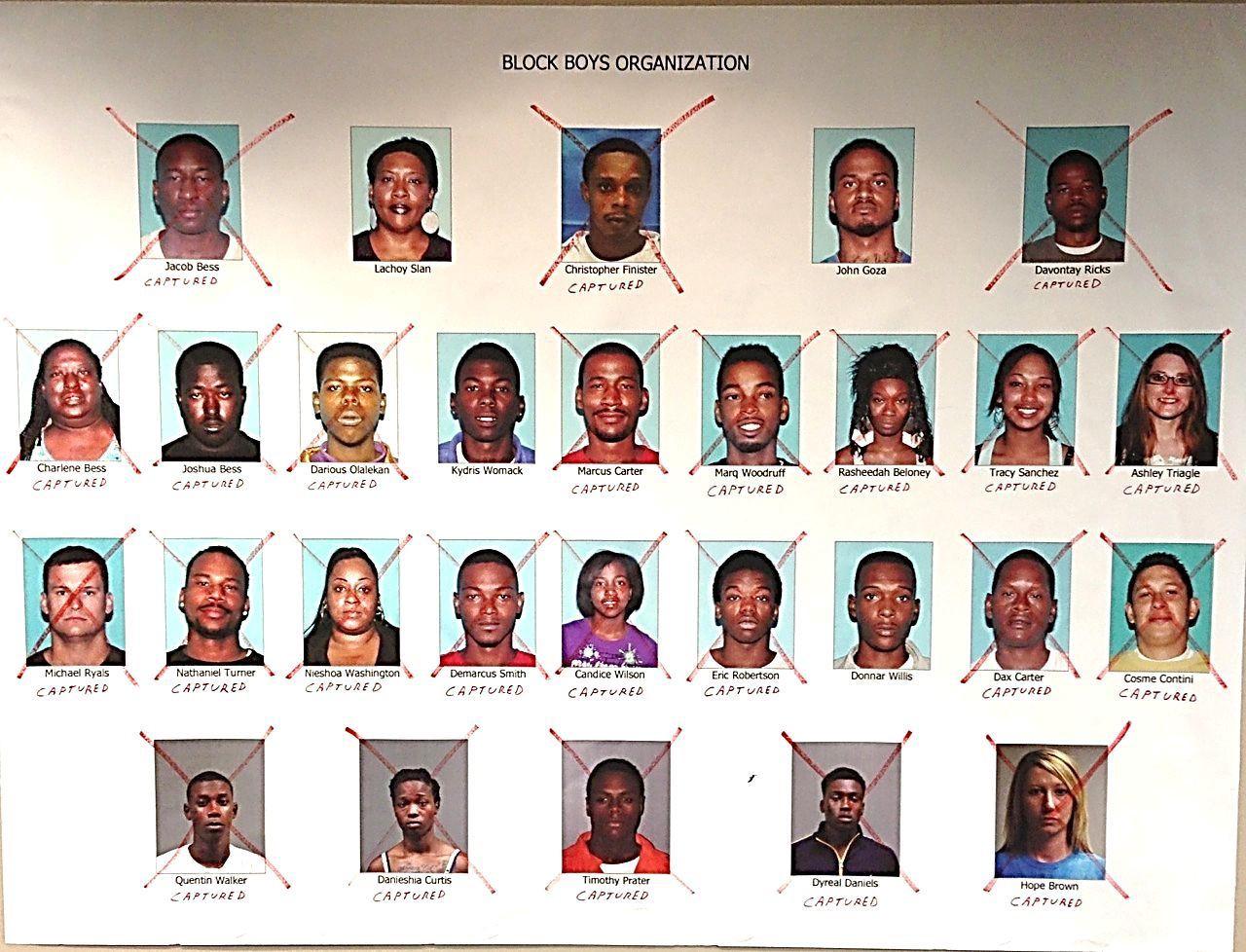

While the social-services side of the BRAVE program failed to attract many participants, Moore’s office initiated its first large-scale gang indictments with data provided by the BRAVE program. On April 10, 2014, Moore’s office handed down a 28-person indictment, focusing on a group it had labeled the “Big Money Block Boyz.” Moore claimed that he had told members of the group that they were being surveilled in April 2013, and that they could either stop committing violent crimes, or face a group-wide crackdown. Moore’s indictment followed through with his threat, using racketeering charges to tie several members of the gang to attempted murder charge Members and associates of the Block Boys Organization in Baton Rouge.

The murder attempt stemmed from a pair of shooting incidents in February of 2014, neither of which left anyone injured — one in which one of the defendants shot at the back of a truck outside a grocery store and one later that day in which another defendant shot at someone’s house. Because of the severity of the charges, the defendants have pleaded guilty to lesser charges, all of which still carry up to 20-year sentences in prison. The indictments also create huge problems for the indigent defense system, because defendants in these cases are almost always poor. Public-defense offices can defend only one of the indicted individuals because of conflicts, leaving the rest to be represented by court-appointed attorneys.

A large-scale gang indictment is “more of a political statement than it is a law-enforcement statement,” says Ferguson, commenting on how it has become trendy for politicians and prosecutors to say they’re using data to help drive down crime.

To that end, the types of databases and social-network mapping that Operation Ceasefire uses have been embraced by politicians from both the left and right. CUNY Law professor Babe Howell has directly traced the rise of data-driven gang policing in New York City to the negative publicity tied to the previous prevailing theory in criminology, “broken windows,” which posited that targeting small, quality-of-life offenses such as drinking in public or vandalism would lead to the prevention of serious crime.

“Declaring a problem like gangs is useful for politicians because it allows them to claim a narrower scope for law enforcement,” said Howell. “But as it has played out across the country, it involves a massive amount of surveillance, done in secret, with no opportunity to appeal inclusion in databases. It allows police to surveil anyone they decide to surveil, which has meant the usual suspects, black and brown youth of color, particularly in poor neighborhoods.”

Howell’s research into gang databases has demonstrated the underlying flaw of this supposedly impartial method — when the police alone are allowed to decide who merits inclusion in a database, the databases themselves reflect the prejudices of the police, and entire neighborhoods become sites of organized criminal activity. A program that was meant to end the “dragnet” style of policing has simply created entire criminal networks out of preexisting communities.

By incarcerating entire social networks of young people, Howell points out, prosecutors and police are planting the seeds for a future where the cycles of poverty and criminality are constantly reinforced, and where neighborhoods are missing young fathers and mothers, as well as sons and daughters who would just be beginning their adult lives.

“To the extent that we’re disrupting communities and taking parents away from their children and preventing people from aging out of these affiliations, we’re creating massive barriers to pro-social development,” Howell said.

By 2015, any effect BRAVE might have had on the murder rate was beginning to wear off, just as that alleged impact wore off in Rochester, New Orleans, Newark, Kansas City, and other cities where Ceasefire had seen initial gains backslide. Moore’s office reached out to Kennedy to seek guidance on how the program could drive the murder rate back down. In an e-mail discussing next steps for the program from this spring, Chief of Administration for the District Attorney’s Office Mark Dumaine admitted, “We have learned that the call-ins do lose their effectiveness once most members have been invited to attend. [David Kennedy] suggests that we pursue individualized call-ins by bringing community and law enforcement members to the targeted individual’s home. We are pursuing this strategy at this time.” By instructing law enforcement to go directly to people’s homes, however, Kennedy’s most recent advice to the project might just reinforce its most troubling aspects.

With BRAVE shut off from federal funding for now, DA Moore has pledged to continue the work that LSU had been performing on data collection, possibly housing the database in his office’s Crime Strategies Unit. But Moore won’t be without substantial support for long. On October 5, Attorney General Jeff Sessions relaunched the DOJ’s Project Safe Neighborhoods, a George W. Bush–era enforcement operation that, building on Kennedy’s work in Boston, promoted federal prosecution of street-level gang activity. In a memo to all US Attorneys, Sessions instructed them to use data-driven methods to identify the most violent individuals. On the very same day, with Moore at his side, then–Acting US Attorney for Baton Rouge Corey Amundson announced a “Violent Criminal Enterprises Strike Force” that would continue the policing work that BRAVE performed, just without the social services. As Moore described it at the press conference, the new strike force will be “BRAVE on steroids, with more than just juvenile offenders.” Freed from federal grants that demanded social services, Moore, an aggressive prosecutor who has sought life imprisonment for non-homicide crimes committed by juveniles, can now pursue gang indictments.

“My fear is that what’s going to happen is that we’re going to invest in this big-data policing infrastructure in the name of protecting ourselves from gangs,” says Ferguson, “but what we’re going to do is catch up entire communities in the data-driven, big-data policing world, and we’re not going to have foreseen the issues in terms of civil liberties and policing that will harm overall crime reduction.”

So the Ceasefire model, which in practice focuses on the use of surveillance and collective punishment, has now become the dominant model for law enforcement in American cities. In Baton Rouge, BRAVE never meaningfully addressed social problems, but offered a major boost to policing and prosecution — the outcome was just more incarceration. No steroids necessary.