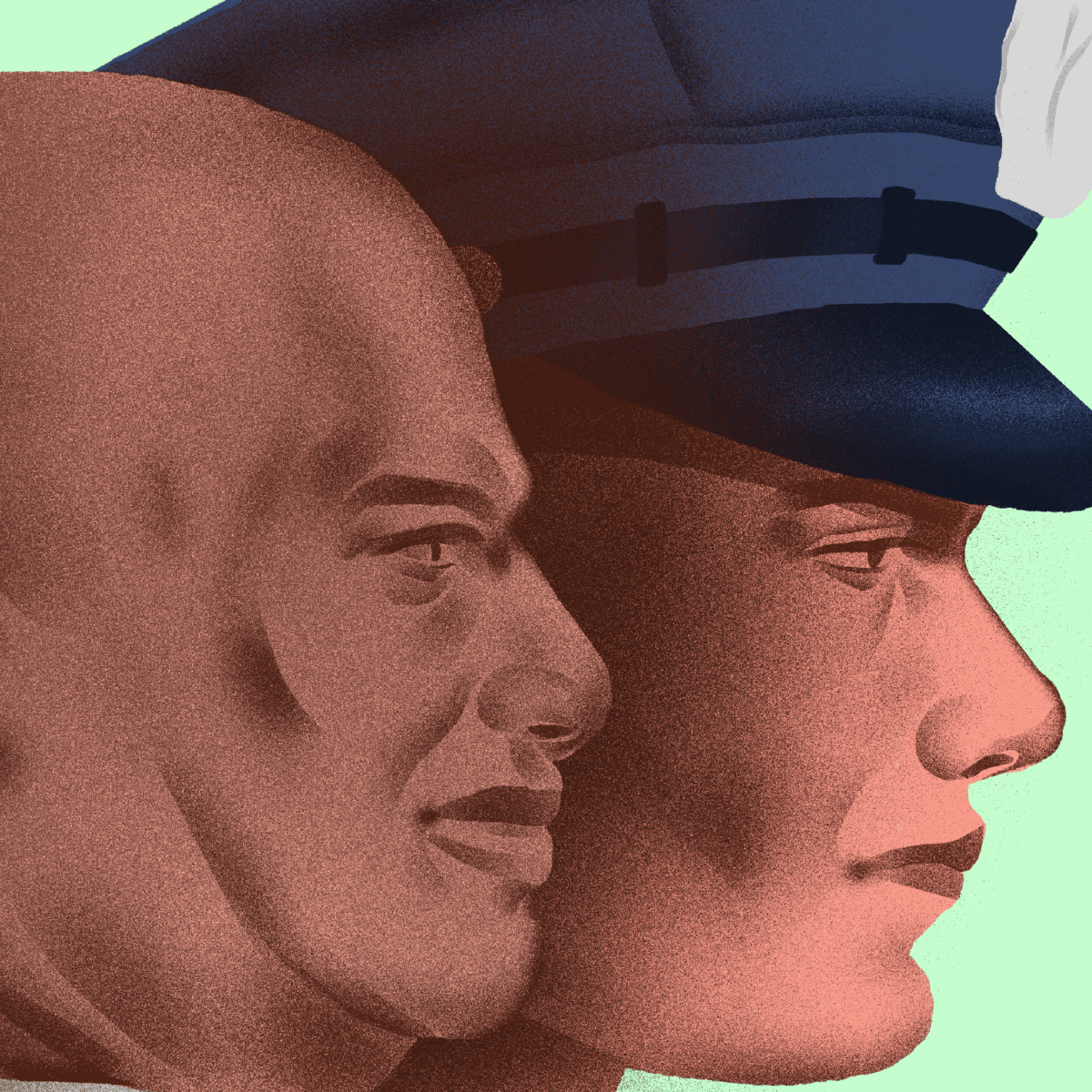

Albany Police Shot a Teen in the Back and Paralyzed Him. The D.A. Said It Was Justified.

Activists suspect the investigation was tainted by the close relationship between the police and prosecutors.

The last day Ellazar Williams had full use of his legs was Aug. 20, 2018.

It was an 80-degree day—warm enough that Williams, 19, could walk around without a shirt. That’s how he appeared in surveillance footage captured that afternoon by cameras at R & A Grocery. In the footage released by the Albany County District Attorney’s Office, Williams can be seen entering the market with a male companion. Williams’s companion argued with the store’s owner before they left without incident.

When they returned to the market a few hours later, a minor disturbance ensued, according to the DA’s office. An object was thrown at the storefront. None of the surveillance cameras showed Williams as the thrower. When he was seen again on surveillance, the teenager was no longer shirtless. He wore a dark-colored hooded sweatshirt and jeans.

A store employee phoned police, telling them that a Black man wearing a gray hoodie and blue, faded jeans had flashed a gun and threatened to use it.

“A whole bunch of people came to the front of the store,” the caller told an Albany police dispatcher. “They brought guns, and they threw a water bottle at the door.”

At approximately 4:30 p.m., Albany Police Detective James Olsen, along with Detectives Christopher Cornell and Lawrence Heid, responded to the call. Williams, walking in the area with a group of young men, fit the 911 caller’s description.

“Police, stop!” yelled Heid, who drove Olsen and Cornell in an unmarked vehicle.

Surveillance cameras recorded Williams as he fled on foot, running into a gated courtyard behind a school. Olsen got out of the car to chase Williams. Although neither of them could see Olsen or Williams, according to authorities, Heid and Cornell claimed they heard their colleague command the teenager to “drop it” and get on the ground.

Then two shots rang out.

Olsen later said he opened fire because Williams ran toward him with a shiny object and, suspecting it was a weapon, he feared for his life and the lives of his colleagues. Williams dropped the object, authorities claimed. But surveillance cameras didn’t clearly capture that part. Footage only shows Williams running from the officer, tripping and getting back up, before he continued to flee. Olsen shot Williams in the back.

Albany police didn’t recover a gun from Williams. However, officers found a large hunting knife nearby. At the hospital where Williams was treated, staff removed a knife sheath from Williams’s jeans and gave it to Albany police detectives. The sheath fit the knife.

One of the two bullets Olsen fired at Williams was lodged in the teen’s spine. Just a few hours after he first appeared at the West Hill market, Williams laid paralyzed from the chest down in Albany Medical Center. More than seven months later, Williams’s attorneys say he is permanently paralyzed.

The shooting has frayed the already damaged relationship between Albany residents and law enforcement, community advocates told The Appeal. For years, the city’s police, clergy and activists had worked to build trust through a series of initiatives that kept some people from coming into unnecessary contact with the criminal legal system. But at the same time, the city was grappling with gun violence concentrated in majority-Black neighborhoods (the city is 55 percent white and 29 percent Black).

By August 2018, police recorded at least 43 shootings and 10 homicides for the year, with nearly half of them occurring in the West Hill neighborhood where Williams was shot. Law enforcement responded to the spate of violence by tasking police detectives with removing illegal street guns in an operation that mostly targeted the capital city’s Black, Latinx and poor-to-working-class neighborhoods. The shooting, and the way city leaders have handled the fallout, has worsened tensions with law enforcement, community advocates said.

While activists called for accountability in the wake of the Williams shooting, Albany County District Attorney David Soares quickly brought criminal charges against the paralyzed teenager. Although surveillance cameras did not catch the moment when Olsen said Williams charged at him with a knife, Soares sought Williams’s indictment for felony menacing of a police officer and misdemeanor weapons possession.

Meanwhile, the DA’s office investigated Olsen’s use of force. The parallel investigation was carried out by the office’s investigative unit, which community activists have criticized as blatantly unfair to Williams. Six of the unit’s nine investigators are former Albany police officers, including two detectives who worked with Olsen. Those investigators have a lot of influence over what’s presented to the grand jury, said Paul Grondahl, a weekly columnist for the Albany Times Union.

“These detectives are practically second-string prosecutors,” Grondahl, who has covered police and crime in the city for over 30 years, told The Appeal. “There’s a weird relationship [between the DA and the investigators], just in general, and that certainly came into play in this case.”

For 16 weeks, the investigative unit compiled the evidence that would be presented to a grand jury. Ultimately, on Dec. 14, 2018, Soares announced that Olsen had been cleared of criminal wrongdoing in the Williams shooting. The grand jury had reviewed the evidence in the case for three weeks, Soares said.

“After interviewing witnesses, reviewing numerous statements, consulting with experts and enhancing distorted video footage, the facts were presented to a grand jury that determined the detective’s use of force was reasonable under the circumstances,” Cecilia Walsh, a spokesperson for the DA’s office, said in a statement emailed to The Appeal.

Olsen, a 22-year veteran officer, retired from Albany’s police force Jan. 4.

After weeks of outcry, Soares dropped the criminal charges against Williams, saying in a Jan. 8 statement that there was “nothing to be gained” from prosecuting the teenager.

While activists called for accountability in the wake of the shooting, Albany County District Attorney David Soares quickly brought criminal charges against the paralyzed teenager.

Just days after Olsen was cleared of wrongdoing, on Dec. 16, Williams filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against Albany police. The complaint alleges that, although Williams had not committed a crime, Olsen chased him and used excessive force, violating his Fourth and Fourteenth Amendment rights to due process and against an unreasonable search and seizure. Cornell and Heid also violated Williams’s rights by failing to prevent Olsen from using excessive force, the complaint alleges.

Williams is seeking unspecified damages for “extensive medical attention since the shooting, including hospitalization, wound care, pain management, neurological care, rehabilitative care, physical therapy, [and] psychological care for depression resulting from being chased and shot and from being permanently paralyzed,” according to the complaint.

Through an attorney, Williams declined The Appeal’s request for an interview.

“We look forward to our day in court, where once again, as with the grand jury, the officers involved will be found to have been acting in self-defense from the actions of a young man who had terrorized a convenience store owner and his family prompting a 911 call and threatened the responding officers with an 8-inch Rambo style hunting knife,” Stephen J. Rehfuss, an attorney for Olsen, Cornell and Heid, wrote in an email to The Appeal.

Steven Smith, a spokesperson for the Albany Police Department, declined to comment, citing the pending federal lawsuit.

Local organizers told The Appeal that they had hoped for change under Soares, the first Black Democratic district attorney in Albany County who, 15 years ago, promised to address racial disparities created by the state’s strict narcotic drug laws. Just before unseating an incumbent white Democrat in 2004, Soares ran on a platform promising to help reform the state’s Rockefeller-era drug laws, which after decades on the books led to the disproportionate mass incarceration of African Americans. Soares won re-election in 2008 and 2012. He ran unopposed in 2016.

“People in the progressive community, including me, we thought [Soares] was going to be a breath of fresh air,” Alice Green, a civil rights activist and founder of Albany’s Center for Law and Justice, told The Appeal. “He hasn’t been good when police officers murder or shoot black people.”

In 2015, Soares angered many in the community when he did not secure a grand jury indictment against four Albany officers accused of using a stun gun on Donald Ivy Jr., an unarmed mentally ill man who died following the encounter, sparking protests and contributing to simmering mistrust of law enforcement. The city ultimately settled with the man’s family for $625,000.

“Justice is blind,” Soares wrote to Albany Mayor Kathy Sheehan in a 17-page letter detailing his office’s investigation. “As leaders, we cannot be blind to problems in our criminal justice system. … Peace for the Ivy family will be achieved only when we have taken all of the steps to ensure that a tragedy like this does not happen again.”

Members of the public are rightly suspicious. They wonder if there can be a full, fair and arms-length investigation that will truly look at whether the officer is at fault.

David Harris law professor at University of Pittsburgh

But Soares’s progressive leanings on other issues have helped establish his profile beyond Albany County. Last year, Soares was elected president of the District Attorneys Association of the State of New York, a lobbying group that represents all 62 of the state’s district attorneys.

Soares supported “Raise the Age” juvenile justice legislation, sponsored a program that diverted youth ages 16 to 24 from the Albany County Correctional Facility and, in December, de-emphasized the prosecution of simple marijuana possession in the county. However, under his leadership, the DA’s association has lobbied against other progressive criminal justice reforms.

In October 2018, the association sued to block legislation that would have created an independent oversight commission for New York DAs. Their opposition immediately froze the commission in its tracks.

“This flawed and unconstitutional bill will unnecessarily and detrimentally interfere with the fundamental duties of our prosecutors and not bring about any meaningful oversight,” Soares said after state lawmakers voted to establish the New York Prosecutorial Misconduct Commission. “The interference will breed more public corruption and distrust of our public officials.”

Soares’s decision not to charge Olsen is far from unusual. It’s rare for a police officer to face criminal charges for injuring or killing someone while on the job. According to research on police accountability, this is in part due to the close working relationship between prosecutors and police, which creates a conflict of interest for prosecutors investigating shootings. An analysis by The Guardian found that 85 percent of the killings by police ruled justified in 2015 were handled by prosecutors who worked with the same police department.

More than 18,000 law enforcement agencies in the U.S. work hand in hand with local prosecutors, who rely on officers to bring cases and to serve as witnesses in criminal courts. Even if the prosecutors conduct the most neutral investigation, the institutional relationships are too close to foster broad public confidence in use-of-force investigations, said David Harris, a University of Pittsburgh law professor who specializes in policing issues.

“Members of the public are rightly suspicious. They wonder if there can be a full, fair and arms-length investigation that will truly look at whether the officer is at fault,” Harris said in a phone interview. “It isn’t that an investigation can’t be done well by a DA’s office, or that these former police officers could not or would not give you a straight investigation, but what you want is for the public to believe and trust that it is so.”

After so many high profile missteps, however, it’s hard to imagine that the public will fully trust the unit’s work, Harris said.

Bringing in an independent prosecutor can head off that perceived conflict of interest. In its final report, released in May 2015, President Barack Obama’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing urged communities to embrace “the use of external and independent prosecutors in cases of police use of force resulting in death, officer-involved shootings resulting in injury or death, or in-custody deaths.”

Many states and counties have considered changes to their policies on officer-involved shootings, particularly after the 2014 fatal police shooting of Black teenager Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, Harris said. After a secretive grand-jury process, then-St. Louis County prosecutor declined to charge Officer Darren Wilson in Brown’s death, sparking nationwide protests.

New York requires that the attorney general take over the investigation of an officer-involved shooting only if the shooting results in the death of an unarmed person. Green had called for a special prosecutor to step in to investigate the Williams shooting anyway, but Soares declined to recuse himself. From his perspective, his office had obeyed Governor Andrew Cuomo’s 2015 executive order requiring him to contact the Attorney General’s and get confirmation that Albany County was the appropriate jurisdiction for the investigation.

“The grand jury found that Det. Olsen committed no wrongdoing, therefore Mr. Williams was never legally declared a victim of crime and a legal conflict did not occur for our office to handle the case to a final resolution,” Walsh, the spokesperson for the Albany County DA’s office, wrote in an email to The Appeal.

Soares was not a supporter of Cuomo’s executive order. In 2015, when Soares was 2nd vice president of the state’s district attorneys association, the group blasted the directive as “gravely flawed” and predicted that it would “harm the cause of justice.”

“District attorneys have far more experience—and resources—in dealing with these cases than either the governor or the attorney general,” Gerald Mollen, a former association president, said in a statement about the executive order. “District attorneys have also learned from long, sometimes painful experiences that or legal system cannot always heal the pain a family suffers from the loss of a loved one. But our system of criminal justice, although not perfect, does work.”

The District Attorneys Association of the State of New York did not respond to The Appeal’s request for comment about police-district attorney relationships.

In February, nearly two months after Olsen was cleared of wrongdoing in shooting Williams, the case was still a point of frustration in the community. On a recent evening at the Center for Law and Justice headquarters, area residents trickled in for a monthly meeting of a racial justice discussion group. The group, led by Green, got its start when several residents expressed interest in legal scholar Michelle Alexander’s 2010 book, “The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness.”

Green had been a key advocate for Albany’s implementation of Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion, a community-based intervention that allows police officers to divert people to a network of harm-reduction services and that chokes the pipeline to incarceration for people struggling with addiction, mental illness, and poverty.

In 2015, Albany police received a $70,000 grant for the program. Coupled with Soares’s commitment to divert youth from the county jail by raising the age of prosecution for certain offenses, LEAD helped reduce the Albany County jail population to historic lows, the DA’s spokesperson said.

Green said she fears Williams’s shooting jeopardizes the progress made under the LEAD program.

“We’ve done a lot of work to change the culture,” Green said at the meeting. “We’ve changed the training of police officers. We’ve diverted a fair number of people from the system, even though [LEAD participants are] disproportionately white.”

About a half-dozen meeting attendees, white, Black and much older than Williams, sat around a long wooden table underneath portraits of civil rights icons Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. Some of the attendees said they had met Williams a few days earlier at a screening of the Marvel film “Black Panther” that Green hosted for Black History Month.

David Walker, 89, of nearby East Greenbush, New York, said he saw that Williams just “wants a chance” to live a productive life. “He could still smile. If we can’t save somebody like this, then we’re doing something wrong,” Walker said at the discussion group.

Community suspicions about the Williams case investigation can’t be swept under the rug, Green said during the discussion group. In a public report that she drafted after the DA’s December press conference, Green called on Soares to clarify what, if any, threat Williams posed to Olsen. Video evidence simply doesn’t support the detective’s claim that the teen charged at him with a weapon, she said. And how is it that investigators tied the weapon conclusively to Williams, Green wondered in the report.

The activist also asked that Albany Police Chief Eric Hawkins—he is the first African American to lead the department in more than 20 years and was confirmed by the City Council one day after Williams was shot—release “a written investigation report to the community that includes all surveillance camera videos, dashcam videos, and or audio recordings in possession of the police department related to the incident.”

Weeks after Green made the requests, Soares responded. “Thank you for inquiring about my public presentation on police use of force,” the DA wrote in a letter dated Jan. 28. “I will be making an announcement regarding the aforementioned subject in the near future.”

In late February, the DA had not followed through, said Green, who concluded that Soares had no intention of opening up about use-of-force investigations. However, in mid-March, Walsh, the spokesperson for the DA’s office, confirmed Soares was making plans for a community event that would be announced “once details are finalized.”

“Our office looks forward to the continued conversation about use of force and the evolving role of transparency for prosecutors in the criminal justice system,” Walsh said. “We have done this during and after previous incidents, and maintain our efforts to have an open dialogue with community.”

Green said that without continued dialogue, it’s possible that the area’s Black teenagers will start to believe that they could be the next Ellazar Williams.

“There has always been major concern that, even though we’ve embraced community policing and we’ve done all these things, those kids on the street are saying, ‘Hey, I don’t know anything about community policing. They’ll still stop me and do the same thing.’”