Alabama’s Prisons Are the Most Crowded—If You Look at the Right Data

The Bureau of Justice Statistics relies in part on states to self-report prison capacity numbers, which can result in a misleading snapshot of overcrowding in the U.S.

In July 2011, police officers who were called to a house in Cottonwood, Alabama, on an unrelated matter found 39 marijuana plants growing in a house and backyard.

The plants belonged to Lee Carroll Brooker, a combat veteran who had chronic physical and mental health problems. Officers seized the plants, which were then weighed in their entirety, though stalks are not used in cannabis consumption. The plants weighed in at 2.85 pounds—above the 2.2-pound threshold that triggers a drug trafficking charge in Alabama, regardless of intent to transport or distribute the substance.

Brooker, then 75, was convicted in August 2014 of a Class A felony, the same classification as murder, rape, and terrorism offenses. And since Brooker had previous felony convictions for a series of armed robberies committed in Florida 30 years earlier, a Houston County circuit court judge sentenced Brooker to mandatory life without parole.

Brooker’s lawyers appealed the sentence to the Alabama Supreme Court in September 2015, arguing that it was unconstitutional in its severity, but the court denied a review of the case. His legal team petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court, which ultimately declined to hear the case. The sentence, condemning Brooker to die in prison, stood.

Alabama’s prison system is full of people like Brooker, serving some of the harshest possible sentences as a result of mandatory minimum terms for repeat offenders. An ACLU report found that, as of 2017, half of the people in the state’s prisons were serving a sentence of 20 years or more, often due to prior felony convictions.

“Alabama has been in a state of crisis for almost a decade now,” said Charlotte Morrison, a senior attorney with the Montgomery-based Equal Justice Initiative. “We have 1 in 4 people in Alabama’s prisons serving either life or life without parole sentences, and those extreme sentences have driven up the population.”

Since the imposition of habitual offender sentencing in Alabama, the prison system has also become severely overcrowded. In a report released in April, the Department of Justice stated that conditions of confinement in the state’s prisons, largely due to chronic understaffing and overcrowding, were so bad that they violated the constitutional right to be protected against cruel and unusual punishment.

One might expect to see this reflected in figures presented by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), the agency that collects data on crime and incarceration throughout the country. But according to the bureau, Alabama is either one of the most—or one of the least—overcrowded prison systems in the country.

How is this the case?

Not long after the DOJ’s investigation into Alabama was published, the BJS released its “Prisoners in 2017” report, a snapshot of the U.S. prison population as it was on Dec. 31, 2017. Most media coverage focused on the top-line finding of a 1.2 percent decrease in prison population from 2016 to 2017 and presented as a cause for some optimism. But the report also contains some of the best state-level information available about overcrowding in America’s prisons.

In one data table, three metrics are used to determine each state’s prison capacity: the design specifications set by the architect, the capacity as assessed by a rating official, and the operational capacity “based on current staffing and services.” The report then lists each state’s prison population as a percentage of whichever values are highest and lowest of the three. For example, in a hypothetical state with a prison design specification of 1,200 people, rated assessment of 1,150, and operational capacity of 1,400, relative capacity figures would be calculated by taking the current population as a percentage of both 1,150 and 1,400 people.

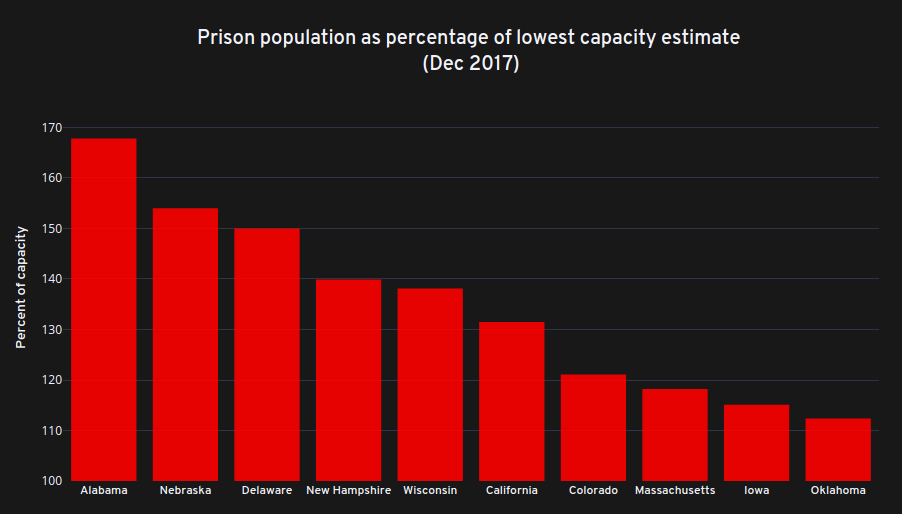

On the basis of the lowest capacity measure, Alabama’s prison system is hugely overcrowded, operating at 167.8 percent of the design capacity with a custody population of 21,570 in 2017. Nebraska had the second-highest level of overcrowding, at 154 percent of design capacity, and Delaware was third, at 150 percent.

Some of Alabama’s prisons are filled to 180 percent of capacity and have chronic staff shortages; in some cases, prisons have only 50 percent of staff positions filled, according to the DOJ report. But by the highest capacity measure in the BJS report, Alabama is listed as having one of the least crowded prison systems in the country.

Why is that? The operational capacity measure is self-reported, which is problematic for estimating overall capacity. It’s the only indicator that gives a state’s department of corrections leeway to present data as it sees fit. Design capacity and rated capacity, however, are calculated by a third party.

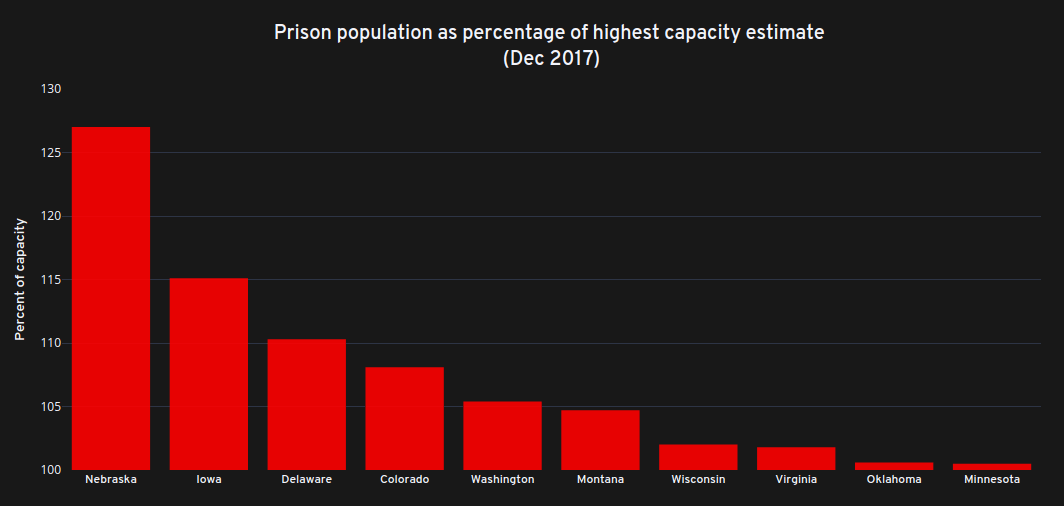

In the report, the BJS makes assertions based on the highest capacity figure, writing that “jurisdictions with more prisoners in custody than the maximum number of beds that their facilities were designed, rated, or operationally intended to have included Nebraska (127%), Iowa (115%), the BOP [Bureau of Prisons] (114%), Delaware (110%), Colorado (108%), and Virginia (102%).”

This gives the impression that prisons in states like Alabama and California are being managed within capacity, and that reporting based on the BJS report in previous years—for example by HuffPost and the Washington Post—has let them off the hook as a result.

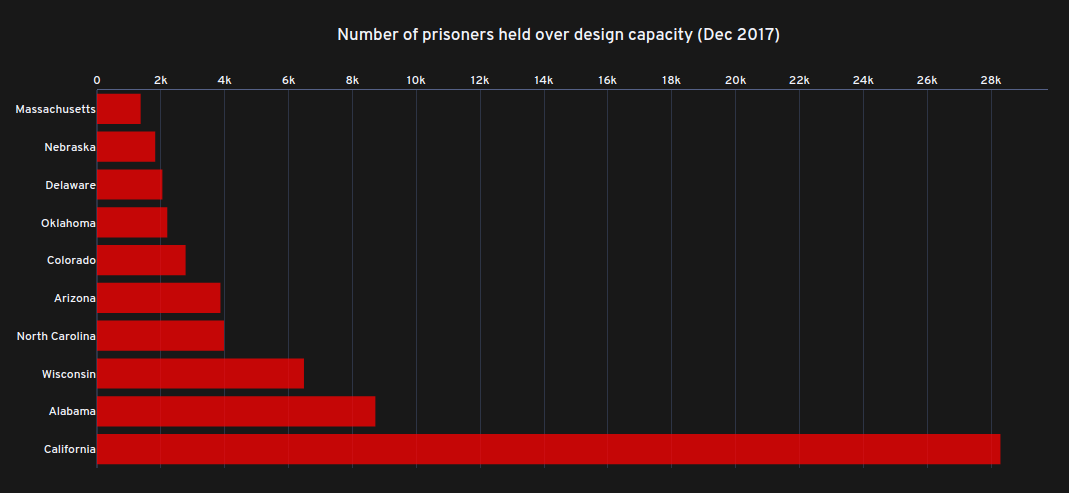

It’s worth noting that comparing percentages doesn’t tell the whole story: for example, California’s prison system is the largest in the country by a wide margin, so a single percentage point represents far more people than it does for a smaller state like New Hampshire.

According to E. Ann Carson, acting chief of corrections at the BJS, the variation in prison capacity measures occurs because of inconsistencies in the way that states choose to define the operational capacity of their prison system. In a phone call, Carson explained: “You’ll have some states that just say, however many people we have, that’s our operating capacity. Others will say, we can have a maximum ratio of 10 or 20 [prisoners] to one [guard], or whatever it is.”

Since the BJS has, in Carson’s words, “neither a carrot nor a stick” when it comes to obliging states to provide data, not all of them supply a figure for rated capacity or design capacity, meaning the self-defined operating capacity might be the only figure that the BJS has to go on. (In a footnote to the report, the BJS notes: “The majority of Alabama prisons were overcrowded. As of 2017, a total of 25,784 beds were in operation, which represented the physical capacity for prisoners but was not based on staffing, programs, and services. The operating capacity differed from BJS’s definition.”)

States may see other incentives to overstate capacity, suggested John Pfaff, professor of law at Fordham University.

“In Brown v. Plata, the Supreme Court upheld a Ninth Circuit ruling that compelled California to reduce its prison population to 137.5 percent of capacity, down from 200 percent where it was initially,” Pfaff said in an email to The Appeal. “And while the Court certainly didn’t lay down a hard and fast rule about a capacity limit of 137.5 percent, it’s certainly possible that states hoping to avoid litigation may try to keep their populations below the line that Plata upheld.”

Although five states are above the 137.5 percent mark on the lowest capacity estimate, Pfaff noted, none exceed the threshold under the highest capacity estimate.

Overall, the number of people in prison across the nation is starting to go down. In the same month that the BJS report was published, nonprofit advocacy group the Vera Institute of Justice released its own report, “People in Prison in 2018,” which showed a 1.3 percent decrease in the number of people in prison from 2017 to 2018.

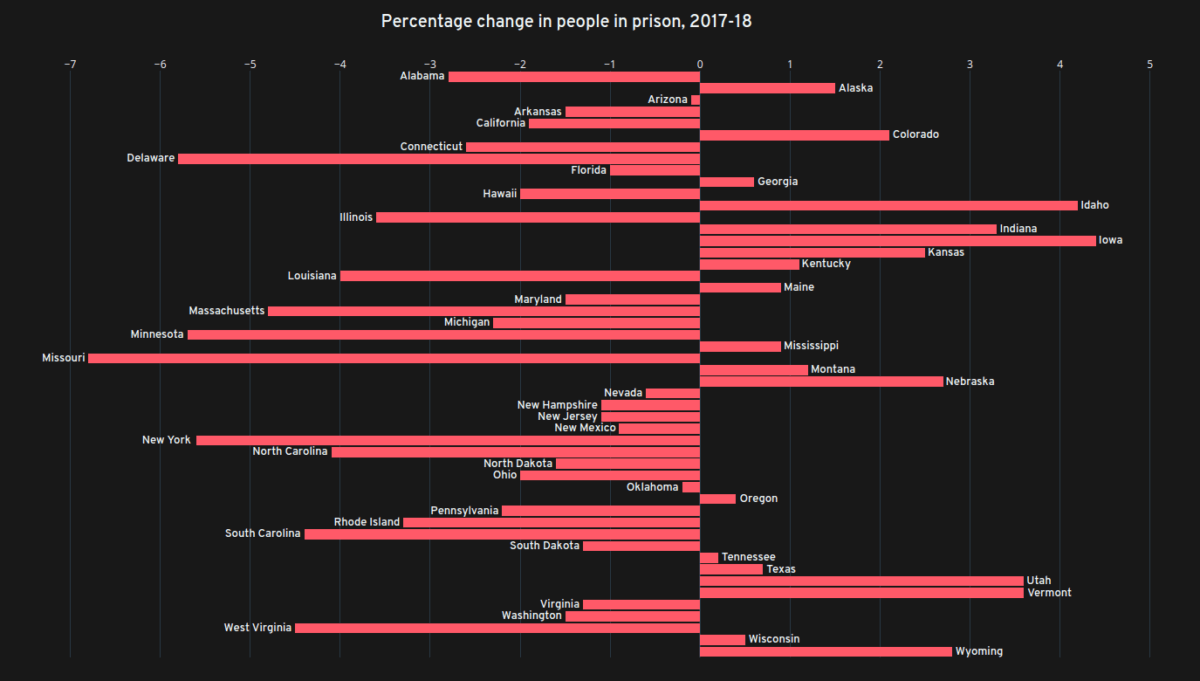

But this reduction is not evenly distributed. In the same period, 19 states have increased their prison population, some of them significantly.

The greatest percentage increase happened in highly rural states, with Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Utah, and Vermont showing the largest prison population growth from 2017 to 2018.

“You’re talking about places with opioid crisis issues, and poverty issues here,” said Wendy Sawyer, a policy analyst with the Prison Policy Initiative, “but these are probably pretty small increases in terms of numbers. If you have a small population and increase it by even five people, that could have a big effect [on percentage change].”

This is certainly true in the case of Vermont, where the absolute number of people in prison increased by just 60 people. In Texas, by comparison, a proportional increase of just 0.7 percent equates to 1,112 more people in prison.

At first glance, prison population statistics in Alabama seem encouraging, with close to a 3 percent decrease from 2017 to 2018. But Morrison of the Equal Justice Initiative was skeptical that this represented a substantial change. “The vast majority of the people released were released due to parole, when the parole board stopped revoking people for technical violations beginning in 2011,” she said. “That is now under threat with new parole laws that were enacted by the legislature this year, so we are actually seeing a rise in the prison population.”

In fact, the most recent data released by the Alabama Department of Corrections shows that the 2017 to 2018 decline in prison population has mostly been erased, with a rise in admissions returning prison population to peak levels.

State Senator Cam Ward, who sponsored two bills aimed at reducing prison overcrowding in 2013 and 2015, and is starting work on a third, is well aware of the difficulty of creating lasting change.

“The general public doesn’t want to talk about prisons, and that bleeds over sometimes into legislature because it’s ‘out of sight, out of mind,’ people just don’t care,” Ward told The Appeal. “We’re a deep red state, a very conservative state, so you’re always fighting against the idea that you’re soft on crime, which we’re not.”

On a positive note, Ward says that it has been easier to find bipartisan support for legislation to reduce prison overcrowding than for other policies, and that faith groups are also starting to take an interest in the issue.

“It is the biggest challenge our state faces right now,” he said. “I don’t think we have a choice: We have to confront this and deal with the problem.”