An Alabama Man On Death Row Says He Is Innocent. Will He Get a New Trial?

In 1998, prosecutors failed to tell the defense that a key witness in Toforest Johnson’s capital murder trial would receive thousands of dollars in reward money for her testimony, Johnson’s attorneys say. Now a Birmingham judge must decide whether their argument has merit.

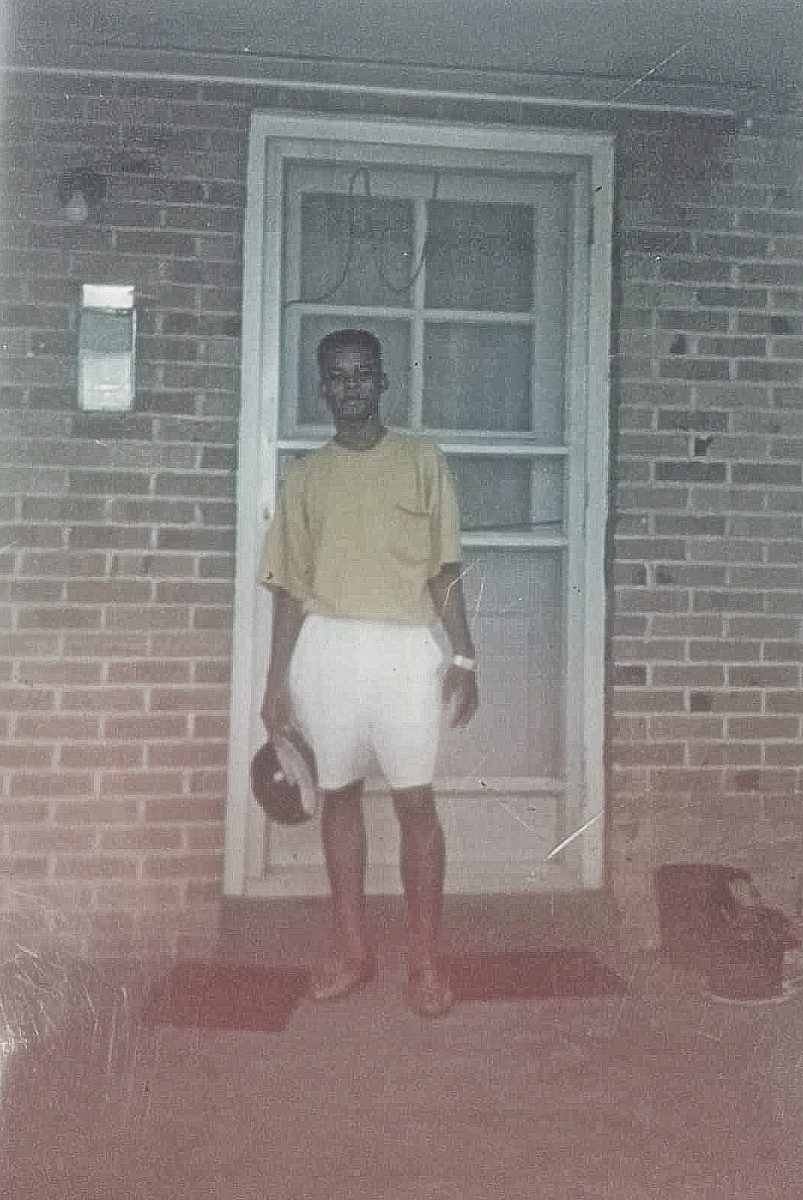

On July 19, 1995, Jefferson County Deputy Sheriff William Hardy was shot dead while working his second job as a hotel security guard. The murder of Hardy, a 23-year veteran of the sheriff’s department, stunned his hometown of Birmingham, Alabama, and police worked frantically to solve the case. Then in a July 27 press conference, police announced a breakthrough: They had arrested four people for the murder, including a man named Toforest Johnson.

Six days later, then-Governor Fob James issued a proclamation that anyone with information leading to the arrest and conviction of the killer would be rewarded $10,000. A local woman named Violet Ellison went to police soon after that and told them she had overheard a man bragging about Hardy’s murder over the telephone. She explained to investigators that her daughter, who would sometimes place three-way calls for prisoners at the Jefferson County Jail, made a call on Aug. 3, 1995, and left the room. Ellison told police she picked up the phone and heard a man who identified himself as “Toforest.” Ellison, according to court filings, said she heard the man boast, “I shot the fucker in the head and I saw his head go back and he fell” and then “Fella shot once.”

Jefferson County District Attorney David Barber charged Johnson with capital murder. There was no physical evidence nor were there eyewitnesses, so Ellison was the star witness at Johnson’s 1998 trial. (She was also the star witness at his 1997 trial, which ended in a mistrial.) On the stand, she testified that she approached police six days after listening to the call because she had a guilty conscience and was having trouble sleeping.

The account that Ellison said she heard over the phone contradicted testimony from hotel guests and the opinions of forensic experts, which both suggested the two fatal shots were fired in quick succession from the same gun. Yet lead prosecutor Jeffrey Wallace told the jury that Ellison was “some of the most important evidence one could find” because she didn’t have a stake in the trial’s outcome. At the conclusion of the trial, a judge sentenced Johnson to die.

Johnson, who has been on death row for 21 years, has always said he is innocent. Now he has a chance at freedom. In June, his attorneys argued that the prosecution never told the defense that Ellison would be paid reward money for her testimony. It’s an issue they’ve raised since 2003, and one that they say is so significant that Johnson should be awarded a new trial because of it. Prosecutors for the state said that they had done nothing wrong, saying that Ellison didn’t know about the money when she testified. Jefferson County Circuit Court Judge Teresa Pulliam must now determine whether the prosecution’s failure to disclose that Ellison would receive reward money warrants a new trial.

Under the 1963 U.S. Supreme Court ruling Brady v. Maryland, prosecutors must turn over all evidence that is favorable to the defense, including evidence that could be used to challenge the credibility of a witness. In 2017, the Court ordered Alabama to hold a hearing to determine whether prosecutors may have violated that decision, known as the Brady rule, by not telling the defense about Ellison’s reward.

In the hearing on June 6, Ellison testified that she was not aware of the money until 2001, when she was contacted by the state to retrieve it, according to a report by WBRC 6. Johnson’s attorneys, however, argued that documents the state turned over this year in January show that Ellison did know about the money, which motivated her to testify against their client. Those documents included a 2001 letter from Jefferson County District Attorney David Barber to then-Governor Don Siegelman, stating that Ellison, “pursuant to the public offer of a reward,” had given information helpful to convicting Johnson and should be paid $5,000. (Barber determined that Ellison should receive half of the initial $10,000 reward because Johnson was already in jail by the time she came forward.)

Johnson’s attorneys learned of the reward in 2003 and asked for documents about it then. The state did not turn them over until 16 years later because the district attorney’s office had “misfiled” them, Mike Lewis, a spokesperson for Alabama Attorney General Steve Marshall told The Appeal in an email.

Marc Bookman, a co-director of the Atlantic Center for Capital Representation, told The Appeal that this information would have been crucial during Johnson’s trial. “The motivation of a witness is highly relevant in any case, and never more so than when a death sentence is involved,” he said. “In a case where the evidence of guilt is shockingly thin, a Brady violation takes on great significance. If a witness testified because she was aware of a reward, that would surely be evidence a jury should have heard.”

In an email to The Appeal, Lewis said that the state did not violate the Brady doctrine because Ellison was “unaware” of the reward when she testified and “at the time of Johnson’s trial, the prosecutor was unaware that Ellison would request the cash award several years after the trial.”

Johnson’s attorneys declined to comment to The Appeal because the issue is pending in court, but they have long alleged that, along with the reward money, there is a wealth of information supporting his innocence that the jury never got to consider. They largely attribute this to a poor performance by his trial attorneys. The attorneys, they said in a 2005 filing, hired only one investigator, who had an IQ of 63 and drank at least a quarter gallon of whiskey every day for 20 years, including when he was working on Johnson’s case. Trial lawyers also failed to call witnesses, Johnson’s legal team wrote, who could have testified that there was a prisoner at the Jefferson County jail who they say “routinely impersonated” Johnson and other prisoners when placing calls to young girls in a bid to impress them. Nor did attorneys call a man who was staying at the hotel the night that Hardy was shot and said he saw a tall man walk away from Hardy’s body. (Johnson is 5 feet 5 inches tall.) And trial attorneys either didn’t call or failed to properly prepare at least 10 alibi witnesses who said they saw Johnson at a nightclub at the time of the shooting, Johnson’s lawyers alleged.

In addition, police arrested Johnson and his co-defendant Ardragus Ford based on the story of a 15-year-old girl who admitted on several occasions, including under oath, that she had lied because she wanted the reward money and then felt pressured by police to stick to her story. At their trials, prosecutors offered opposing theories on who shot Hardy: At Ford’s 1999 trial, they argued that Ford was the shooter, and at Johnson’s trial, they told the jury that Johnson and a friend had killed Hardy. Ford was acquitted of all charges.

If Pulliam does grant Johnson a new trial, newly elected Jefferson County District Attorney Danny Carr has the discretion to decide whether to prosecute the case. Carr ran for district attorney as a progressive candidate who pledged to ensure that his team complies with the Brady rule. But even before Pulliam makes a decision, Carr could influence the case by pushing for a new trial and asking Marshall to drop his challenges to the claim that prosecutors had acted improperly.

“There is no question that the district attorney’s opinion in the jurisdiction he was elected to serve carries a powerful moral force,” said Bookman, “particularly in a capital case where there is the possibility of an innocent man’s execution. If he feels that a new trial is appropriate, one would hope he would say so.”

Carr declined an interview with The Appeal, citing the ongoing litigation.

In addition to the claim before Pulliam, Johnson also has an appeal pending in federal court that includes claims that Johnson’s trial attorneys were ineffective, prosecutors violated the Brady rule, and also illegally struck Black jurors. And in May, his attorneys filed a request that the state throw out Johnson’s death sentence because Wallace, the lead trial prosecutor, told them and Carr earlier this year that he had “grave doubts” about Johnsons’s guilt. Wallace also backtracked on his stance on Ellison’s testimony in 2014: “I don’t think the state’s case was very strong, because it depended on the testimony of Violet Ellison in my opinion,” he said in a post-conviction hearing.

Ellison’s daughter, Katrina, who testified for the state in 1998 about placing the 1995 phone call to the Jefferson County jail that led to Johnson’s conviction, agreed. “I think he does deserve a fair trial,” she told The Appeal. “The only thing they had was the phone call and that’s not right. That wasn’t strong enough to hold, to convict somebody to death.”

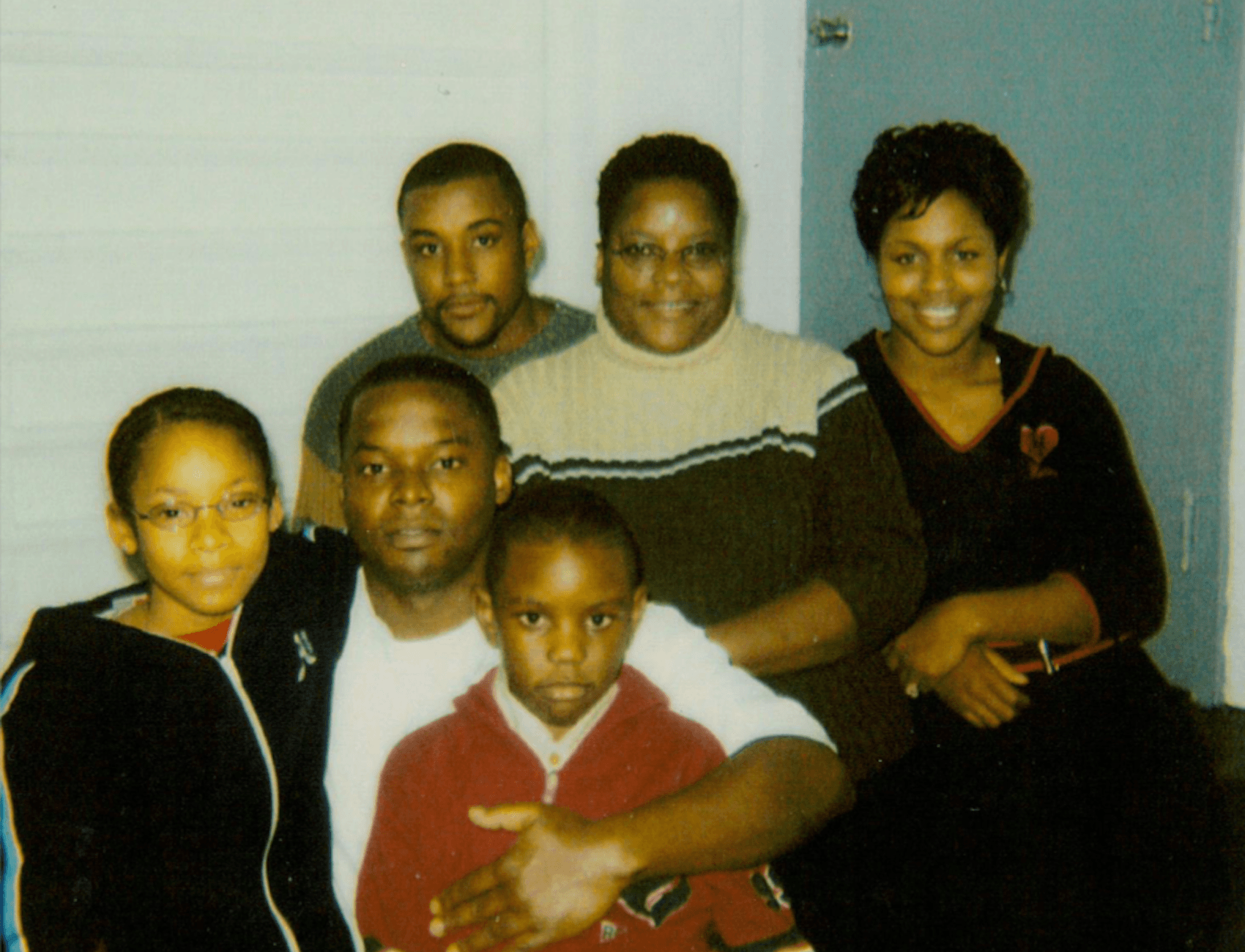

Alabama courts have denied Johnson’s requests for a new trial two times in the past, but his daughter, Shanaye Poole, told The Appeal that the latest developments have sparked a newfound sense of hope for her family. Now 27, Poole was 5 years old when she watched a judge sentence her father to die. “I just honestly can’t wrap my mind around it,” she told The Appeal. “It’s hard for us but at the end of the day my dad has been sitting there for 20-plus years. He is who my heart breaks for every single day.”