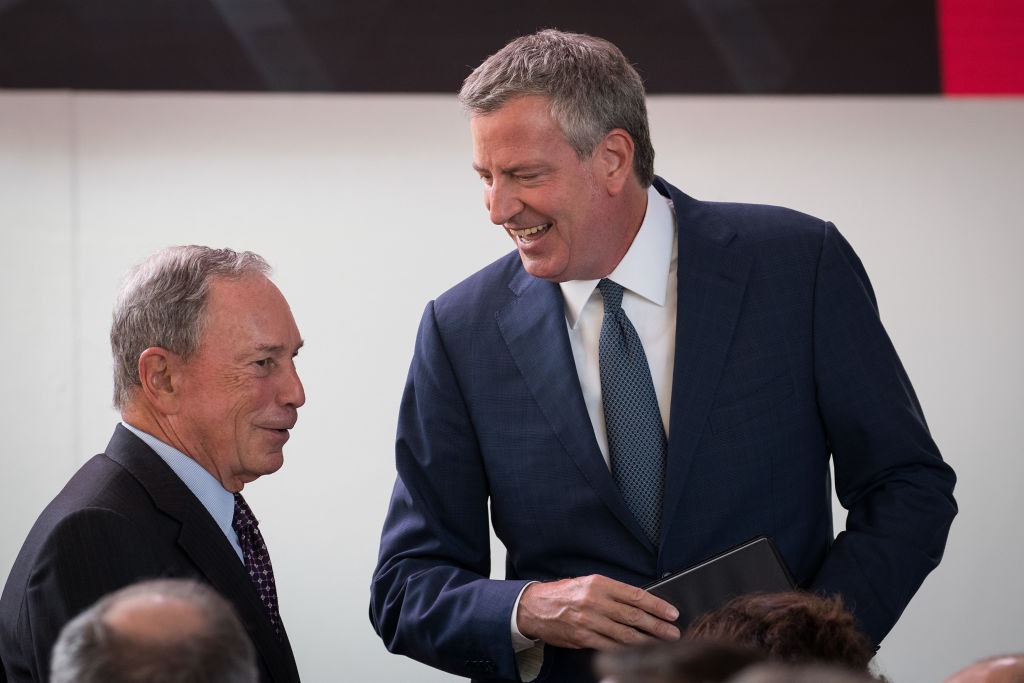

A Tale Of Two Mayors

Spotlights like this one provide original commentary and analysis on pressing criminal justice issues of the day. You can read them each day in our newsletter, The Daily Appeal. New Yorkers were supposed to be finished with all of this. Done with 12 years of Michael Bloomberg, a technocratic, out-of-touch billionaire mayor who oversaw the highly […]

|

Spotlights like this one provide original commentary and analysis on pressing criminal justice issues of the day. You can read them each day in our newsletter, The Daily Appeal. New Yorkers were supposed to be finished with all of this. Done with 12 years of Michael Bloomberg, a technocratic, out-of-touch billionaire mayor who oversaw the highly discriminatory and destructive stop-and-frisk policy. On his watch, hundreds of thousands of people, overwhelmingly people of color, were stopped by the police each year. New Yorkers were done with Bloomberg’s predecessor, Rudolph Giuliani, who, before becoming the Trump sycophant he is today, was ruining the lives of poor people of color across the city by ushering in broken-windows policing policies. When Bill de Blasio became mayor in 2014, after running on a platform of police reform, a federal judge had already ruled that stop-and-frisk was unconstitutional. Under Bloomberg, the city appealed the ruling, but as mayor, de Blasio dropped the appeal. The idea was that he was going to make things right. It didn’t happen. Events of the last week have shown how slow change can come, even after aggressive policing tactics are rejected by the courts and by the voters. Bloomberg, for his part, apologized for stop-and-frisk on Sunday. “I was wrong,” Bloomberg said. “And I am sorry.” Of 575,000 stops that police conducted in 2009, Black and Latinx people were found to be nine times as likely as white people to be stopped, though no more likely to actually be arrested. In 2011, officers made about 685,000 stops; 87 percent of people stopped were Black or Latinx. “Over time, I’ve come to understand something that I long struggled to admit to myself: I got something important wrong,” he said. “I got something important really wrong. I didn’t understand back then the full impact that stops were having on the black and Latino communities. I was totally focused on saving lives, but as we know, good intentions aren’t good enough.” The existence of the apology itself is remarkable. “It is almost unheard-of for a former chief executive to renounce and apologize for a signature policy that helped define a political legacy,” writes Shane Goldmacher for the New York Times. “Even for a politician as dexterous as Mr. Bloomberg—who ran first as a Republican, then as an independent and now, possibly, as a Democrat—the reversal left his longtime observers astonished.” Other politicians who have been in the race officially for months, including Kamala Harris, Amy Klobuchar, and Joe Biden, have also been responsible for inflicting serious harms to many people using the criminal system, and none of them have approached this level of apology. But it was not nearly enough for some, including many of those in attendance at a Black megachurch in Brooklyn where he made the apology, which responded with mild applause. “It’s too late and too facile, especially coming at a time when it serves Michael R. Bloomberg’s electoral interests,” Robert Gangi, the director of the Police Reform Organizing Project, wrote in a letter to the editor in the New York Times. “Especially when he defended the tactic for years in the face of undeniable evidence that it was racist and illegal. He even said, ‘I think we disproportionately stop whites too much and minorities too little.’” It is hard to argue with this sentiment, and yet Gangi also adds, “Bloomberg is paying the price for not restraining the Police Department’s worst practices.” In this regard, it is remarkable that stop and frisk has become one of Bloomberg’s most significant vulnerabilities if he were to run for president. The dialogue, at least, has shifted. “It was also, in some ways, a last word on an era of aggressive policing in New York City that began a generation ago under former Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani,” Goldmacher writes. Although he adds that “the fallout on neighborhoods is still felt to this day,” Goldmacher is wrong. It isn’t merely aftershocks that’s kept neighborhoods feeling the effects of stop and frisk. It is the deliberate continuation of policies that have had a substantially similar effect. De Blasio, for his part, slammed Bloomberg’s apology, calling it “a death bed conversion” ahead of the 2020 election. “People aren’t stupid,” de Blasio, who dropped his Democratic presidential bid in September, told CNN. “They can figure out whether someone is honestly addressing an issue or whether they’re acting out of convenience.” But days later, when the police commissioner that de Blasio himself appointed stepped down, he took the opportunity to defend the NYPD’s use of stop and frisk. In an interview on 1010 WINS, the departing commissioner, James O’Neill, called it “a constitutionally-tested tool that police have to use.” He added, “It helps keep the city safe.” De Blasio also has recently faced criticism for passing over Benjamin Tucker, the second-highest-ranking official in the police department, when it came time to replace O’Neill. Instead of appointing Tucker, who is Black, de Blasio chose Dermot F. Shea. He is the third white, Irish-American police leader that de Blasio has appointed to the post. De Blasio has promised that police leadership would be more and more diverse “in the coming years.” NYPD policies themselves have continued the harassment of poor people of color under the new mayor. This has played out in particular on the subway system, as The Daily Appeal has reported. Recently, police forcibly removed a man from an L train because he placed his bag on an empty bench seat; they punched a teen on a subway platform; they pulled guns on an unarmed teenager suspected of having a gun (who turned out to be unarmed, and was later cited for fare evasion); and, in two separate incidents, police handcuffed women selling churros and confiscated their property, accusing them of not having the proper license. When video showing police accosting a tearful churro vendor was shared widely, de Blasio defended the police. “I understand the facts. The facts are she was there multiple times and was told multiple times that’s not a place you can be, and it’s against the law and it’s creating congestion,” he said. “She shouldn’t have been there,” he added, and “the officers comported themselves properly, from what I could see.” Officials have ordered for 500 more police officers to patrol the subways, even though crime is down, not only on the subway, but also in the city more generally. Still, as O’Neill told interviewers, he believes police are useful, even if people are already safe, just so that people also feel safe. “You have to control the entrance to the subway,” O’Neill said. “We have to make sure we do our best to make people feel safe. Not only be safe, but feel safe.” |