A New Power for Prosecutors is on the Horizon—Reducing Harsh Sentences

Legislation in California would provide a direct route to resentencing, and a new tool for activists.

In 2017, Santa Clara District Attorney Jeff Rosen decided that Arnulfo Garcia did not belong in prison. Sentenced under California’s three-strikes law, Garcia was serving a life sentence for a residential burglary he committed while suffering from a heroin use disorder. During more than 16 years in prison, Garcia, then 64, had turned his life around. He became a prolific writer and editor-in-chief of the award-winning San Quentin News, a newspaper produced by incarcerated people and distributed throughout the California prison system. He completed drug treatment and led support groups for fellow prisoners. He organized forums with prisoners and prosecutors, helping to show those responsible for sending people to prison that even people who commit serious offenses are capable of profound change.

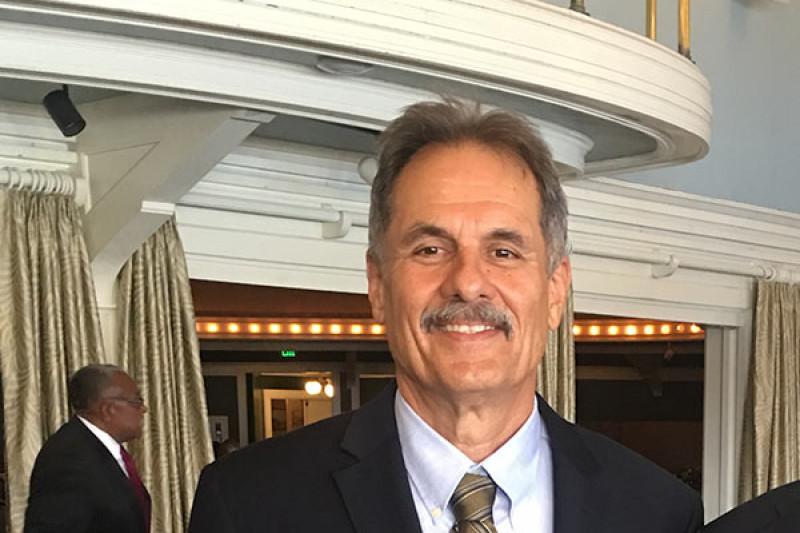

Rosen was among the prosecutors who attended Garcia’s meetings, returning on several occasions to discuss reforms to California’s criminal justice system. Rosen later told reporters that Garcia was “more than a model inmate”: He “was a better man, he was helping other people, using his talents in a productive way,” and “he’d served enough time.”

Rosen wanted to reopen Garcia’s case to reduce his sentence. But under state law, Rosen could not simply ask a judge to resentence Garcia without a legal basis for doing so, like new evidence or a change in sentencing law that would entitle Garcia to relief. It wasn’t enough to say that Garcia, while guilty of his crime and legally sentenced, was rehabilitated and deserved to go home.

It’s an issue faced by a growing number of reform-minded prosecutors around the country. As more elected prosecutors break with their tough-on-crime predecessors and pledge to reduce prison populations, more prosecutors have started to review old convictions to identify cases where, even if the conviction was sound, the punishment did not fit the crime. As reported by The Marshall Project, about two dozen prosecutors have announced plans to review old sentences, including Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner, the former public defender and civil rights lawyer, who in March announced the creation of a formal sentence review program.

But identifying an excessive sentence is only the first step. In many states, prosecutors lack the legal authority to revisit sentences simply because they believe them to be unjust. Instead, they must devise creative workarounds. In some cases, prosecutors have joined prisoners’ clemency petitions or agreed to renegotiate prior sentences as though they were settlement agreements, options that may not be available in every case. In Garcia’s case, he was eventually released after Rosen supported his petition for a writ of habeas corpus, a complicated and lengthy process that required his own lawyer to concede ineffective assistance of counsel. (Garcia died in a car accident just two months later.)

“We had to do these legal gymnastics to get people resentenced,” Rosen said, “and realized the most straightforward way to make this happen would be to change the law.”

Now California is poised to do exactly that, with legislation on Governor Jerry Brown’s desk that its supporters say would be the first “legal vehicle” in the country to give prosecutors the power to recommend reducing sentences “in the interest of justice.” Rosen sponsored the bill and other Bay Area prosecutors—Alameda County District Attorney Nancy O’Malley and San Francisco County District Attorney George Gascón—joined organizations that advocate criminal justice reform, including the ACLU of California and the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights, to endorse the measure.

Once a prosecutor makes a recommendation, a judge would still have to impose the new sentence, and the sentence must be allowed by law. But just as prosecutors have enormous power to seek harsh penalties when a defendant is first sentenced, so too could prosecutors demand leniency after someone has already spent many years in prison.

The law could especially benefit prisoners whose sentences were lengthened when prosecutors tacked on sentence enhancements, Rosen’s office said. That would include sentences under California’s three-strikes law, which could be reduced if prosecutors withdraw a prior conviction (or “strike a strike”) from the court’s consideration. Other sentence enhancements, like those related to drugs or guns or alleged gang affiliations, could also fall by the wayside at the prosecutor’s discretion.

This would allow for resentencing not just in a case of clear rehabilitation, but also to keep up with modern sentencing practices. It doesn’t make sense to keep people in prison serving lengthy terms they would never receive today, Rosen said. “In my experience as a prosecutor, I’ve become aware of more cases from the Santa Clara DA’s office, or even that I prosecuted myself, where the person was convicted and was in prison for a very long sentence, and if we had to do it all over again today we would ask for a lower sentence.”

Rosen said the new law would do more than create a mechanism to reduce sentences—it would codify sentence review as part of the prosecutor’s job, making clear that prosecutors have a responsibility to see that no one sits in prison unnecessarily. “People think we use discretion to pile onto people,” he said, but “we can also use discretion to mitigate, and to show leniency and mercy in appropriate situations.”

The ‘next frontier’ of criminal justice reform

The legislation was the brainchild of Hillary Blout, a former prosecutor who has spent the last four years advocating criminal justice reform in California. Blout sees sentence review as the “next frontier” of reform: Securing justice for people still languishing in prison under long sentences imposed when the era of mass incarceration, defined by harsh sentencing laws and tough-on-crime prosecutors, was at its peak.

For decades, California was at the forefront of a national trend to send more people to prison for longer periods of time. From 1977 to 2007, the state’s prison population jumped nearly 900 percent, propelled by new sentencing laws—including an especially severe three-strikes law passed in 1994—and prosecutors that piled on sentence enhancements to obtain longer prison terms. Reforms over the last decade have pushed prison totals down, but the changes have been limited in scope, benefiting mainly low-level offenders convicted of nonviolent offenses.

The result is a prison population that, while about 25 percent smaller than it was 10 years ago, is still the second largest in the country and now has a higher proportion of prisoners serving long-term sentences. According to the most recent data from the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, 25 percent of California’s 130,000 prisoners are serving a life sentence, and 31 percent are serving a sentence enhanced by either a second or third strike. As of September 2016, according to the Public Policy Institute of California, 80 percent of California’s prisoners carried a sentence enhancement of some kind.

Longer sentences also mean older prisoners. Since 1990, the share of California prisoners age 50 or older has jumped to 23 percent from 4 percent. That means the state’s prisons are increasingly filled with people who are among the most expensive to house and statistically least likely to commit crimes.

Advocates say that sentence review can be the impetus for more inclusive reform that reaches the prison population that has so far been left behind.

Keith Wattley, the executive director of UnCommon Law, which represents prisoners serving life sentences in parole hearings, says that taking another look at the people serving long-term sentences will challenge false distinctions that set boundaries on prior efforts to reduce incarceration. “Reforms come up,” Wattley said, and “people convicted of violent crimes are left out. People serving life sentences are left out.” They are based on “fundamental false premises—like there are differences between people who commit violent and nonviolent crimes, that one is redeemable while the other will always be too dangerous.” In reality, Wattley said, many people serving long-term sentences, even for violent offenses, remain in prison only because of outdated policies and pose no threat to public safety.

His view is supported by emerging research that lengthy prison terms do little to protect public safety or deter crime. A 2016 report from the Brennan Center for Justice, for example, summarized existing research and concluded that longer prison terms may actually produce higher recidivism rates, and at best provide diminishing returns for public safety. The report estimated that about 212,000 prisoners nationwide (14 percent of the U.S. prison population) convicted of serious offenses (including aggravated assault, murder, and “serious burglary”) could be released from prison without a threat to public safety.

Meanwhile, other research shows that long prison terms — and particularly the use of sentence enhancements and repeat offender laws — hit African Americans and other racial minorities the hardest.

California Assembly Member Phil Ting, who introduced the bill, said that California’s reliance on long sentences needs correction. “Looking at the last 30 years where we’ve overincarcerated people, we realized that longer prison sentences don’t really mean safer communities.” Giving prosecutors the discretion to reconsider these sentences, Ting said, “makes sense.”

An ‘organizing anchor’ for prosecutor accountability

Still, there remain questions of whether and how often prosecutors will use the law. The legislation does not mandate sentence review, but rather provides district attorneys with a tool to use at their discretion.

The district attorney offices in Santa Clara and San Francisco said they will formalize the process for sentence review under the new law. For example, according to a spokesperson, the San Francisco district attorney’s office will use the same “conviction review initiative” that investigates claims of wrongful convictions to identify excessive or disproportionate sentences.

Reform advocates are also preparing to maximize the law’s impact.

Blout has launched the Sentence Review Project, a new organization designed specifically to “spearhead implementation of the new law.” Blout says the Project will tackle everything from recommending criteria that district attorneys should consider when reviewing past sentences, to supporting prisoners who submit applications for sentence review, to advocating a reduced sentence in individual cases. The initial work will start with the Bay Area prosecutors who endorsed the legislation, with plans to expand around the state. “We will be inviting prosecutors to sit down with us,” Blout said, “and to join us on prison visits, restorative justice circles, and opportunities for DAs to the see the humanity in these men and women.”

Like Wattley, Blout wants this new legislation to expand the conversation around who deserves a chance at redemption. “California has made great strides in reform for nonviolent, nonserious offenders,” she said, “and the goal for this Project is to push that narrative to include redemption and second chances even for people who have committed serious or violent offenses.”

Raj Jayadev of Silicon Valley De-Bug, a hub of community organizing and criminal justice reform, said the new law “can be used as a tool to advance the work of prosecutorial accountability.” Jayadev plans to work directly with prisoners, their families, and their communities to make the case that people warehoused on long sentences deserve a chance at redemption. “These are elected DAs that are accountable to their communities,” he said, and “this project will give a tangible organizing anchor for communities to insist on the freedom of their loved ones.”

To Jayadev, sentence review is a logical extension of prosecutorial discretion. “Prosecutors have all the power to prosecute and punish people. If they have the power to get someone jailed for 50 years, they should have the power to say that doesn’t make sense and we should get this person home.”