A Melee Broke Out On The Subway—and then the Bronx DA Prosecuted One Of Its Victims

Walliris Velez thought the worst was behind her after she was slashed in a subway car, but then came an arrest and an attempted murder charge by the Bronx DA.

Four years ago, Walliris Velez’s mother warned her to stay away from the Puerto Rican Day Parade, afraid of what could happen if the crowds—which in years past have ballooned to over 1 million attendees—got rowdy. “My mom doesn’t like crowds,” Velez remembers, “because she’s always watching the news and thinks bad things could happen. She’s very overprotective of us.”

On June 7, 2014, as Velez, then 27, made her way back from the parade on a packed northbound 5 train, her mother’s fears were realized. “A group of loud people barged in, everyone turned around, and one of them, the girlfriend slapped her boyfriend,” Velez remembers. “I said to myself, ‘They should leave that at home.’” The boyfriend caught Velez’s gaze and told her, “Mind your fucking business.” Velez says that when she tried to respond, “he mushed my face, I looked at him like, ‘Are you serious?,’ then they all jumped me.”

Velez, who was slashed by the one of the melee participant’s glasses during the fight remembers seeing only wildly swinging arms and feet as she hit the subway train floor. Friends carried an injured Velez off the 5 train at the 149th Street-Grand Concourse stop; but when she attempted to climb the station stairs, she passed out. Later that day, at Lincoln Hospital in the Bronx, she was visited by NYPD detectives. Velez told the police that she had just defended herself during the subway attack; she recalls that an officer offered to drive her to the precinct to press charges against her attackers. She took up his offer but after waiting for hours in the precinct, a separate officer came and placed her under arrest. “You’re getting arrested, one of the girls is pressing charges,” she said the officer told her. “I was confused,” Velez remembers, “what just happened?”

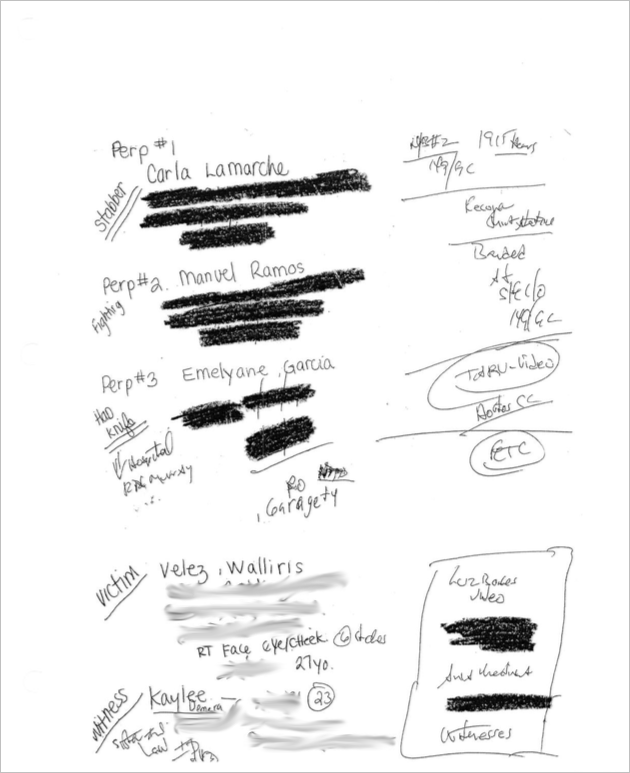

The next day, a police officer reported that Velez had struck one of the attackers with a closed fist—charging her with multiple assault and gang assault charges and criminal possession of a weapon. In the fall of 2014, the Bronx District Attorney’s Office tacked on a charge of attempted murder in the second degree. Velez entered a not-guilty plea and assumed the case, even though it included gravely serious charges, would end with prosecutors dropping it or a not-guilty verdict at trial. Video surveillance footage from the subway, a police radio call, NYPD detective notes and a knife found on one of her accusers all pointed to the fact that she was a victim, not the perpetrator, of the Puerto Rican Day Parade altercation. But the case against Velez took three and a half years to resolve, and her attorney claims that the Bronx District Attorney’s Office office withheld this key evidence that could have exonerated her.

Indeed, in late December of 2017, Velez was acquitted on all charges in Bronx County Supreme Court. But the case had devastating personal consequences for Velez, a single mother who struggled to keep her fast food job as the legal proceedings dragged on. In the months before the trial, she says she was forced to send her two daughters to Puerto Rico because she couldn’t make ends meet. Six months after she was acquitted, her daughters are still on the island.

Kristin Bruan, Velez’s public defender and a staff attorney at the Legal Aid Society, told The Appeal that police and prosecutors often don’t use the wide discretion they have when bringing cases against low-income defendants like Velez. “They didn’t have to arrest her,” said Bruan. “When it’s Eric Schneiderman, they investigate him before they arrest him, but when it’s a poor person of color, they take a complainant at their word and arrest the person, there’s something wrong there. … It sends a message that there’s no such thing as ‘innocent before proven guilty.’”

Bruan says that Velez was put at further disadvantage when discovery materials—pretrial evidence about the case gathered by the prosecution—were not shared with the defense until the fall of 2015, more than a year after Velez entered a not-guilty plea. Also, the state did not turn over exculpatory evidence that was favorable to Velez until 2016 and 2017, according to court documents. Such evidence included a knife that was recovered from one of the accusers; medical records indicating that one of her accusers was released into police custody the day of the incident; the arresting officer’s memo book in which he reported that at least one of Velez’s accusers was identified at the perpetrator at the crime scene; a police radio call describing another one of Velez’s accusers as one of the perpetrators; and a subway surveillance video that corroborated information in the radio call.

During pretrial hearings in the summer of 2017, Velez’s attorneys say that prosecutors continued to withhold exculpatory evidence such as a detective’s notes identifying Velez as a victim in the subway melee.

Bruan says that Velez’s case is emblematic of the plight of poor defendants in New York’s criminal justice system. New York’s “Blindfold Law”—which allows prosecutors to withhold discovery until the day a trial begins—along with the fact that a small fraction of cases go to trial makes prosecutors the “gatekeepers of the evidence in question” and leaves “no doubt that Brady violations are rampant and that the vast majority are never uncovered.” Brady violations refer to 1963 Supreme Court decision requiring prosecutors to disclose materially exculpatory evidence in the government’s possession to the defense.

The Bronx District Attorney’s Office did not respond to requests for comment on Velez’s case nor its policies on turning over evidence to defense attorneys.

When the case finally went to a jury on Dec. 22, 2017, Velez was consumed by anxiety. “I was really scared, I couldn’t eat, stand still, I used to cry every single night,” Velez remembers. The morning the verdict came down, Velez said goodbye to her 13-year-old son for what she thought could be the last time seeing him as free woman. “‘Today they tell me if I come back home,’” Velez recalled telling him. “He starts crying. I said, ‘You gotta be tough, don’t worry, you’re going to be OK.’ I didn’t want to cry, jumped in a cab and went to court.”

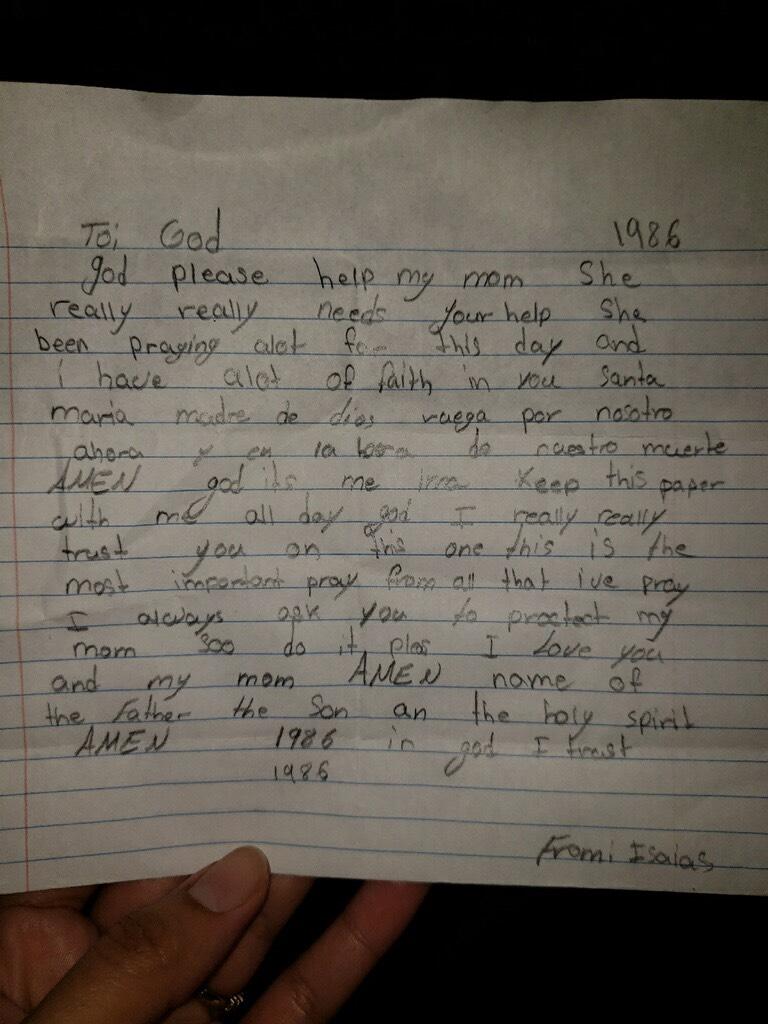

After the not guilty verdict was returned that day, Velez went home and found her son praying. “He wrote letters, saying ‘God please help my mom,’” Velez says.

Though Velez was victorious at trial, she says she has not forgiven the Bronx District Attorney’s Office for the trauma its tactics inflicted on her family. “My cop friends were telling me the DA doesn’t care about who’s getting charged,” she says. “At the end of the day they go on [living their lives]. Everybody else gets screwed.”

Her travails in the criminal justice system have made Velez perpetually wary of prosecutors from the Bronx DA’s Office. Velez believes “they’re people you can’t trust. I will never trust the DA, never, it was a horrible experience. … What they put me on wasn’t right. They accused me of things I did not do, building up a case against me they [weren’t] sure themselves about.”