A Baby’s Death, a Flawed Autopsy, and a Mother Locked Up for Life

Tina Rodriguez was sent to prison in Texas for allegedly starving her son to death. But recent discoveries about the medical examiner who conducted the baby’s autopsy raise questions about her case.

This story was produced in partnership with KXAN.

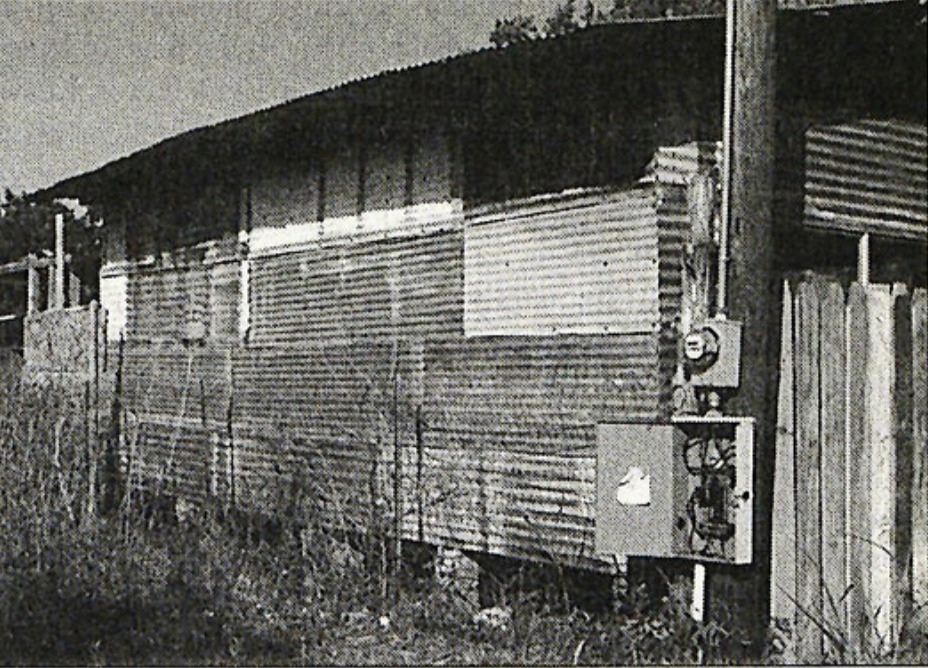

Early in the evening of February 11, 1998, in the Texas Hill Country, southwest of Austin, a 911 operator got a call about an infant in distress. Several emergency medical technicians and a deputy sheriff headed to a rural area near the town of Bandera, to an address that turned out to be a tin-roofed shack with no running water. They found a large family living there: a father, a mother, and four young children. The youngest, 2-month-old Ramiro Perez, wasn’t breathing. The techs tried to revive him, but he was dead. His mother was crying, distraught. The baby had not yet been baptized, she told the emergency medical technicians.

Attempting to calm the mother, EMT Lynda Cook went through the motions of baptizing the tiny corpse.

The dead baby was emaciated. His eyes sank into deep sockets. His stomach caved in, his ribs protruded, and his thighs were stick-like, with sagging, wrinkled skin. At birth, he had weighed almost six pounds. But instead of gaining at least four more since then, as a healthy baby would have, Ramiro had lost several ounces. When he died, he weighed five and a half pounds.

In the following days, local law enforcement and child protection officials descended on the shack and questioned the baby’s parents: Noel Perez Silva, 31, and Ernestina “Tina” Rodriguez, 24. They focused on Rodriguez. She said she had been breastfeeding Ramiro, and also giving him formula and sometimes regular milk. The investigators looked inside the shack and found almost no food there. Two of the surviving children were underweight. All three showed signs of neglect.

The family was desperately poor. Perez worked only intermittently in construction. Before Ramiro was born, Rodriguez had a full-time job as a food service worker at a nursing home, making $6.50 an hour. She had given birth to her four children in three and a half years and was pregnant again, this time with twins.

The officials in the Hill Country investigated for almost a week. Meanwhile, another investigation was taking place 100 miles away. The day after Ramiro died, a medical examiner in Austin, Dr. Roberto Bayardo, did an autopsy on the baby, which included sending body fluids for laboratory tests.

Bayardo’s conclusions from the autopsy helped to cast Tina Rodriguez as a monster who had rejected her baby and cold-bloodedly starved him to death. A year later she was tried for capital murder, convicted, and sentenced to life in prison.

That was in 1999. Since then, and especially during the past few years, some of Bayardo’s older work on death cases has been exposed as faulty and unscientific. As a result of these revelations, several Texans charged with homicide, including some sent to death row, have had their charges dropped and their sentences overturned.

Despite the new knowledge about Bayardo’s errors, however, Tina Rodriguez’s case has not been revisited. Yet evidence ignored at the time of her trial suggests she may not be a baby murderer. She may instead have simply been an impoverished, overwhelmed, and underserved mother who suffered a terrible tragedy and then was the victim of botched forensics.

Bayardo’s track record

In 1998, when Dr. Bayardo did Ramiro Perez’s autopsy, he was the chief medical examiner for Travis County, Texas, which encompasses Austin. He had held the position since 1978, and his office did autopsies not just for Travis, but for 45 surrounding counties, too, including Bandera. For each autopsy that Bayardo did for an outlying county, he was allowed to keep around $250.

One outlying county that contracted with Bayardo was Williamson. That was where Michael Morton and his wife, Christine, lived—until she was bludgeoned to death in 1986. Largely as a result of Bayardo’s autopsy work on the case, Michael was accused that year of murder.

Dr. Bayardo’s autopsy had fixed Christine’s time of death sometime before 1:30 a.m. Michael left home for work that morning at about 6, so Bayardo’s time-of-death finding suggested that Michael killed his wife while he was still at home.

Bayardo had decided on 1:30 a.m. after he found semi-digested food in Christine’s stomach from her dinner the night before, including mushrooms, tomatoes, olives, and squash, according to Texas Monthly. Bayardo said he could look at the food and tell the time when Christine’s stomach stopped functioning and thus know when she died. Michael was convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison.

Bayardo also did autopsies in child death cases and concluded that the children were murdered deliberately or by particular individuals—though later analysis, by other pathologists, suggested that the deaths had been accidental or caused by someone other than the accused.

In 1994, 3-month-old Brandon Baugh died of head injuries. His babysitter, an impoverished white woman named Cathy Lynn Henderson, was accused of deliberately murdering the infant, then burying his body and fleeing from Texas. Henderson confessed that she had accidentally dropped the baby on a hard surface, then tried to hide the death. But Bayardo did Brandon’s autopsy and concluded that the damage to the baby’s head was too severe to have been caused accidentally.

Henderson was tried for capital murder, convicted, and put on death row.

In 1996, an 11-year-old African American girl, Lacresha Murray, who lived with her siblings and grandparents in Austin, was babysitting 2-year-old Jayla Belton. Late in the afternoon, Murray rushed to her family with Jayla in her arms and said, “She’s cold.” The little girl was dead by the time she reached the hospital.

Bayardo did Jayla’s autopsy and determined that her liver was split in half. The little girl had clearly suffered a blow to her stomach, and the fatal injury, Bayardo concluded, had been inflicted just minutes before her death. The only person who had been with Jayla at that time was Lacresha.

Bayardo did three autopsies on the day he did Jayla’s. He seemed rushed. He did not weigh Jayla’s body, which is standard procedure. And, though he found many bruises on the little girl, he did not examine them in detail to estimate exactly when they were inflicted: Minutes ago? Days ago? Weeks ago?

Lacresha Murray repeatedly denied having hurt Jayla, but after hours of relentless police questioning and threats, she confessed to possibly dropping and kicking the child. She became the youngest person in Travis County history to be charged with capital murder. She was convicted of criminally negligent homicide and injury to a child, and sentenced to 20 years in prison.

Rodriguez on trial

Lacresha was convicted in 1996, two years before newborn Ramiro Perez died in the tin shack.

Dr. Bayardo examined Ramiro’s body, then dissected it to do the autopsy, according to the report and his trial testimony. In the boy’s stomach, he testified, he found a “scant amount” of milk. From an eye, he extracted vitreous fluid—considered a more accurate biological sample for testing than blood. Bayardo sent the fluid to a laboratory to test for substances such as creatinine, sodium, and glucose.

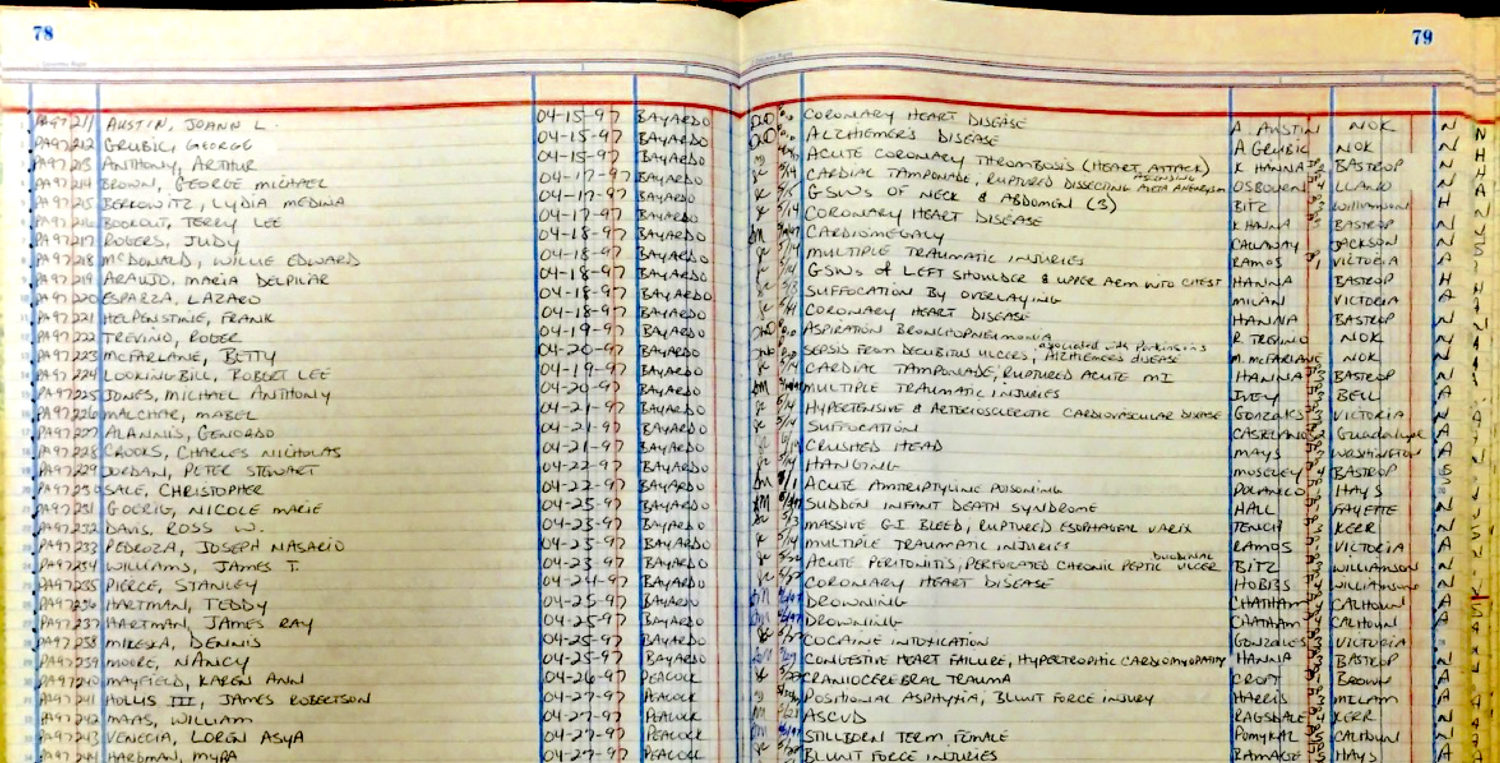

In his autopsy ledger, he wrote “starvation” next to Ramiro’s name. He also penned an “H” for homicide.

Bayardo would later testify that he was surprised when the results came back and showed almost no glucose in Ramiro’s body.

Regardless, Bayardo concluded that the baby’s death was caused by someone not feeding him. In his autopsy ledger, he wrote “starvation” next to Ramiro’s name. He also penned an “H” for homicide.

Rodriguez told investigators that Ramiro was a wanted child. She said she fed him regularly. She said she thought he was thin because she had not received prenatal care, didn’t know her due date, and that nurses had told her Ramiro was premature when he was born. She could not explain why she hadn’t taken him to the doctor for a check up, or why she had not noticed that the baby looked like a skeleton when he died.

As soon as Bayardo’s findings were given to the people who were investigating Rodriguez in the Hill Country, they adopted the theory that she had murdered her baby. So did the local district attorney’s office. Rodriguez was indicted for capital murder.

Rodriguez hired Eric Dean Perkins, an attorney in Corpus Christi. Perkins teamed up with San Antonio attorney Michael Collins, and the two charged a combined “minimally retained” fee of $10,000. That was all Rodriguez and her family could afford. Properly defending a capital case generally costs 50 times this amount.

Two years after Rodriguez hired Perkins, he received a reprimand from the state and had to pay $3,000 in restitution to a client to whom he had failed to return a fee. He received another reprimand in 2003, as well as a two-year sentence of probation—a period of special scrutiny by the state bar association—while still being allowed to practice. And in 2010 Perkins was again reprimanded for not returning money to a client, this time to the tune of $10,000.

At Rodriguez’s trial in 1999, Perkins and Collins mounted almost no defense. The state was accusing Rodriguez of rejecting her baby and intentionally murdering him. Yet her lawyers did not call EMT workers to testify about Rodriguez’s visible anguish after her son died. They never interviewed her co-workers and supervisor. If they had, the attorneys would have heard about Rodriguez’s evident pleasure at being pregnant, about how she brought the baby to the nursing home to show him off—and how she nevertheless seemed tired, depressed, and pale.

And the lawyers did not address the perplexing question of how Ramiro could have been so obviously wasting away, yet Rodriguez didn’t take him to a doctor.

A similar case

In the late 1990s, the question of how a mother could watch a baby lose dangerous amounts of weight but not notice was being discussed in New York City and nationally. In the Bronx in 1997, a 19-year-old African American woman, Tabitha Walrond, was accused of starving her 2-month-old son to death, and she was charged with manslaughter.

Waldron had breastfed the baby but was not aware that breast reduction surgery, which she’d had a few years earlier, could impede milk production. She said she had not noticed that the baby was becoming emaciated. Like Rodriguez, she was poor. She had tried to take the baby to a clinic but was turned away because the child did not yet have a Medicaid card. She did not persist in finding a doctor.

Tina Rodriguez and Tabitha Walrond both went to trial in 1999, but the cases had very different outcomes. The local chapter of the National Organization for Women (NOW) mounted an aggressive campaign on Walrond’s behalf and staged demonstrations demanding leniency. The group also encouraged the public to write to the judge and to prosecutors. Those officials received hundreds of letters. Many were from mothers who said that they, too, had almost lost babies to starvation while breastfeeding.

Lactation experts testified at Walrond’s trial that breastfeeding mothers who see an infant daily may not notice even extreme weight loss, until the child is put on a doctor’s scale. Walrond was convicted of the lesser charge of criminally negligent homicide. Her sentence was five years of probation.

In Texas, Tina Rodriguez’s attorneys did not put lactation experts on the stand. And although Walrond’s case had drawn headlines in New York, the attorneys did not reference it in Rodriguez’s defense.

Nor did Rodriguez’s lawyers educate the jury about the danger to a breastfeeding baby of his mother having had four children in three and a half years, followed immediately by another pregnancy (she later miscarried her twins while in jail). An expert could have talked about damage to a woman’s health in this situation—damage that could diminish her milk supply and exhaust her, physically, mentally, and emotionally.

Rodriguez’s attorneys did not bring in experts to discuss these issues.

And, perhaps most disturbing, they failed to pursue the strange finding in Dr. Bayardo’s autopsy: the extremely low level of glucose in baby Ramiro’s body.

After the trial, one juror said the panel was eager to hear something, anything, from Rodriguez’s lawyers that could establish reasonable doubt about her guilt.

All it would have taken is one expert opinion.

Donald Downer juror in Rodriguez’s trial

Was she being controlled or abused by her husband, the jurors wondered. They were not told that Noel Perez Silva had a wife and children in his native Mexico; or that the Rodriguez family suspected that Perez Silva was beating Rodriguez. (She acknowledged in a recent interview with Austin TV station KXAN that he hit her once, but she denied that it happened regularly.)

Did Rodriguez have mental health problems? Her mother later said that after Ramiro was born her daughter seemed to be in a fog. Yet Rodriguez’s lawyers did not ask about this during the trial. And they never had their client examined by a psychologist or psychiatrist.

Did baby Ramiro have a disease that caused him to lose weight?

“Her lawyers could have brought somebody in to refute the prosecution’s starvation theory,” juror Donald Downer said in 1999 when he was interviewed shortly after the trial. “All it would have taken is one expert opinion. The defense attorneys were obviously not doing their jobs.”

Perkins did not respond to repeated emails and calls to his office. The Appeal also called Collins’s listed office telephone number several times, but there was no answer.

“As a jury,” Downer said, “we were required to weigh only the evidence presented. And based on what we were given, there was really no option. We did what we had to do.” The jury convicted Rodriguez of capital murder, sentencing her to life in prison.

Noel Perez Silva, Rodriguez’s husband, was treated much more leniently. He accepted a plea deal to the charge of child endangerment and was sentenced to 25 years in prison, with eligibility for parole after half that time.

Rodriguez’s appeal was assigned to a young attorney, Adrienne Zuflacht. Within days, she had found and interviewed the EMTs and Rodriguez’s co-workers. Zuflacht also quickly found two nutrition experts at the University of Texas at Austin, Drs. Steven Clarke and Margarita Teran. Clarke reviewed Bayardo’s autopsy of Ramiro Perez, including the lab results. He told Zuflacht that a low glucose level is a marker for a rare congenital disorder in newborns, a problem with the enzyme pyruvate dehydrogenase or pyruvate carboxylase. When these enzymes are defective, babies cannot turn carbohydrates into energy. Without treatment, they waste away, no matter how much they are fed. They die.

Zuflacht got a statement from Clarke about the disorders and filed a motion for a new trial. A higher court ruled that the trial judge should review the new evidence Clarke offered. The judge reviewed it, but he refused to order a new trial.

A pattern of mistakes

Then Dr. Bayardo’s history of previous, sloppy autopsies began to surface. In early 1999, just months after Rodriguez was convicted, Lacresha Murray, the young babysitter, was released from prison because of legal issues regarding the validity of her confession. Her defense attorney had a medical examiner in Florida re-examine the medical evidence. Dr. Bayardo had said Jayla, the 2-year-old, suffered her fatal injuries just minutes before she died. But the Florida examiner concluded that Jayla was injured before she came to Lacresha’s home. Charges against Lacresha were finally dropped in 2001.

Another decade passed, and in 2011 Dr. Bayardo talked to John Raley, an attorney for Michael Morton, the man serving life for murdering his wife, Christine. Bayardo told Raley that his time-of-death estimate in the 1986 autopsy, based on the vegetables in Christine Morton’s stomach, was not scientific and the prosecutor should not have claimed that it was during closing arguments. The lawyer took Bayardo’s statement to court and to the press.

In 2013, Texas passed landmark legislation that is often called the “junk science law.”

Michael Morton was exonerated in 2011 by other evidence: DNA material that indicated Christine’s murder had been committed by another man—a man later implicated in the murder of a woman two years after Christine’s death. Michael was released from prison.

In 2013, Texas passed landmark legislation that is often called the “junk science law.” It was the first law nationally to enable criminal convictions to be overturned based on forensic evidence later shown to be unscientific. Since the law was passed, several death penalty cases have been sent back to courts for review. The new law covers faulty science about infant trauma, and convictions have also been overturned in cases involving children thought to be homicide victims.

The junk science law came on the heels of Bayardo’s testimony, in 2012, recanting his earlier findings in the 1994 death of Brandon Baugh. Bayardo stated then that he could no longer say with scientific certainty that the baby’s fatal fall had been caused intentionally by his babysitter, Cathy Lynn Henderson, instead of by accident.

Henderson was granted a retrial but ended up accepting a plea bargain that credited her with time served and left her with only four more years in prison. She died of natural causes in 2015, shortly before her scheduled release.

In 2016, a few months before Henderson’s death, KXAN looked into Dr. Bayardo’s botched record as a medical examiner. Investigative reporters David Barer and Josh Hinkle found the office’s logbooks and discovered that Bayardo had routinely done far more autopsies per year than is recommended by the National Association of Medical Examiners.

The association recommends that an examiner do no more than 325 autopsies annually. More than that creates a risk for error. Yet for years, according to his ledger, Bayardo had routinely performed more than that, and in some years did more than double the maximum number recommended. During his three decades in the Travis County medical examiner’s office, he supplemented his salary with almost $2.6 million earned through thousands of out-of-county autopsies.

In 1998, the year he did Ramiro Perez’s autopsy and determined the child was starved to death, Bayardo performed over 800 autopsies. On the day he did Ramiro’s, he also did four others, according to his ledger.

Bayardo retired in 2006 and now lives in Houston. The Appeal sent him a copy of his autopsy of Ramiro, and asked to interview him about it. He would not talk on the record.

Rodriguez looks back

Tina Rodriguez has now been imprisoned for 20 years, in the Hobby Unit, a Texas women’s prison between Austin and Dallas. She lost custody rights to her three surviving children years ago and has no idea where they are or how they are doing. She has no lawyer. Until she was contacted recently by The Appeal, she was completely unaware that questions have arisen about work done by the medical examiner who performed her son’s autopsy.

She has spent the decades working in the prison garden, kitchen, print shop, and in the laundry, where she ironed prison officials’ clothes.

Via phone calls and letters to The Appeal, she said she is still trying to understand why she did not see that her baby was dying.

“I was feeling overwhelmed, tired, and depressed,” she wrote. “I was 24 years old with 4 children ages 3 years old to a couple of months. … I did not notice that Ramiro was thin.” She had moved to the shack because her husband wanted to buy land nearby, Rodriguez said, and he had connections in the area but she had no one. She now wishes she had not followed him. “If I could relive my 20s,” she wrote, “I would take my son Ramiro to his 2-month checkup. I would talk to someone about my depression and tiredness. … I would not move to Bandera to be isolated away from my family and friends.”

She entered prison a young woman, and when she comes up for parole in 2038, she will be 64.

Austin attorney Keith Hampton has experience representing Texans who have been falsely accused of murdering and otherwise harming children. He did the post-conviction work for babysitter Lacresha Murray, challenging Bayardo’s faulty autopsy findings in that case. He said he is not surprised by Rodriguez’s fate.

Poor people in Texas, Hampton said, “don’t get a lawyer of their choosing.” In cases such as Rodriguez’s, lawyers need resources and knowledge to mount a defense. Defending Rodriguez, he said, was “obviously heavily dependent on experts.” Not doing the work to find them was “as good as denying her a defense.” Hampton said he regularly sees cases that were inadequately defended at trial. He said he feels frustrated at how difficult it is to make a successful claim of what the law calls “ineffective assistance of counsel.” In Rodriguez’s case, for instance, the appeals court found there was no evidence of ineffective counsel preserved in the record.

Since baby Ramiro Perez died 21 years ago, Bayardo’s former employer, the Travis County medical examiner’s office, has adopted the standards of the National Association of Medical Examiners, including a prohibition on doing too many autopsies. The state’s junk science law has also made it easier for defense attorneys to acquire and use information about contested forensics in child fatalities. That knowledge has percolated to the public via the media.

These reforms are recent. But Tina Rodriguez’s capital murder conviction is starting to feel like ancient history. She entered prison a young woman, and when she comes up for parole in 2038, she will be 64. If she does not make parole, she will likely die in prison.

She still insists on her innocence. “I loved all 4 of my children,” she wrote in a February 2019 letter. “And to this day I still love them.”