51 Years In Prison For A Car Crash

Prosecutors wanted to make an example of Justin Dixon, who has been in an Arizona prison for 14 years, with 37 ahead of him. Now, as COVID-19 spreads in the facility where he’s being held, his family is desperate for him to be released.

Sheila Dixon used to collect newspaper clippings: Officer fined in traffic death. Driver who killed 5 to serve 1 year. Bishop gets probation for hit and run. She put them in a storage box alongside the transcripts from her son Justin Dixon’s trial. In 2006, he was sentenced to more than 51 years in prison after he drank at a Phoenix bar and crashed his car. She never thought his sentence was fair and hoped that one day something might change. But 14 years is a long time to hope. Fifty-one is even longer.

Today, with the coronavirus outbreak sweeping through prisons across the country, Sheila fears for her son. And the facility where Justin is held—the central unit of the Arizona State Prison Complex, Florence—has the most COVID-19 cases of any state-run prison in Arizona. So far, 80 of the 3,448 people incarcerated in the facility have tested positive. At least two have died. But only 4.7 percent of the prison’s total population has been tested so far. Elsewhere in the country, where mass testing has been made available for incarcerated people, huge clusters of cases have been identified.

Just after midnight on June 5, 2005, Justin, then 21 years old, got in his car after having several drinks and crashed into two other cars. Everyone was injured; no one died. When police arrived at the scene, they couldn’t find Justin.

Justin, who sustained head trauma, says the next thing he remembers is waking up on the ground nearby later that morning. He later was taken to the hospital and contacted the police.

Prosecutors sought to make an example of him. Vince Goddard and Allister Adel charged him with four counts of aggravated assault, one count of endangerment, and one count of leaving the scene of a serious accident. They sought a 71-year sentence.

Adel and Goddard flouted the requests of Justin’s victims, who thought that he should receive a 10- to 15-year prison sentence. They asked the court to sentence him to 15 years for each of the four victims, to run each aggravated assault count consecutively, and to stack an 11-year sentence for leaving the scene on top of that.

At Justin’s sentencing hearing in December 2006, Goddard told the judge that there was “nothing in Arizona that gives any benefit whatsoever to staying at the scene” and so “a message needs to be sent” that if you flee the scene of an accident, there will be consequences.

When Sheila heard Justin’s sentence, she was in shock. She doesn’t remember leaving the courtroom or going down the elevator. All she could think was, “He’ll be 70—he’ll be 70. And I … I don’t know if I’ll be alive to see him get out.”

The following year, the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office bragged about Justin’s sentence in its annual report, noting that it was “the longest sentence ever handed down for a vehicular crime in Maricopa County.” Next to Justin’s case, another crash was highlighted. A man on meth and ecstasy ran three red lights and killed a woman. He was sentenced to 27 years.

Today, Goddard is prosecuting capital cases in Maricopa County, and Adel runs the prosecutor’s office in Maricopa, the fourth most-populated county in the U.S. Goddard had left for Pinal County, but returned to Maricopa after Adel was appointed and is now the division chief for specialized prosecution.

Her predecessor actively lobbied against criminal justice reform measures at the state Capitol, but Adel has said she is open to criminal justice reform and believes prosecutors “bear great responsibility to be fair and ethical.” Asked in December about her office’s history of overcharging, Adel said she did not have direct knowledge of any cases where that has happened since becoming county attorney.

But in response to calls to reduce the prison population by releasing certain nonviolent offenders, Adel penned an opinion article for the Arizona Republic, the state’s largest newspaper, stating that activists are “exploiting COVID-19 to release inmates and push their prison agenda.” In it, Adel likened those asking for prisoners to be released to people who hoarded protective equipment and disinfectant for profit at the start of the pandemic.

The Appeal contacted Adel about Justin’s case and asked if she still stood by the 71-year-sentence she sought 15 years ago, or if her views on the fairness of this sentence have changed in the intervening years.

In an emailed statement, Adel responded: “As a prosecutor, I understand and respect the enormous trust placed on us by the community and I strive every day to be fair and ethical in my decision-making. Considering the facts of this crime and the character of the defendant, as demonstrated by his prior criminal history and through his conduct during trial and since conviction, I believe the sentence imposed was appropriate and I stand behind the prosecution of this case. In 2008, the Arizona Court of Appeals also affirmed Mr. Dixon’s conviction and sentence.”

Jared Keenan, staff attorney with the ACLU of Arizona, disagreed. “At the end of the day, the only reason this person got a sentence that so clearly doesn’t fit the crime is because of the decisions by the prosecutors involved in the case,” he said. “They chose to charge and prosecute the case in a way that basically extracts the highest amount of time allowed by Arizona law. That much time is just cruel for the sake of being cruel.”

Justin has had a long time to think about what happened. He said he feels guilty for harming the other people on the road that night. At the same time, he thinks his sentence is beyond reason and longs to get out and be a part of his daughter’s life.

“When it comes to the victims in this case, I feel horrible. … It was never my intention to hurt anyone,” Justin told The Appeal via email. “I mean that’s like hurting my grandparents. I am not that kind of person.”

“The hardest part of this sentence for me to deal with is how I have missed out on my daughter’s life,” Justin said. She was 2 when Justin was arrested for the accident. Now she’s 17. “I missed out on her first day of school, I missed out on her dance competitions, I missed out on her basketball games, I missed out on her first school dance, now I will be missing out on her high school graduation.”

On the night of June 4, 2005, Justin and his then girlfriend, Sara Clyde, headed to the Valle Luna bar to meet up with friends and sing karaoke, according to testimony from Justin’s trial. They arrived around 11 p.m. and sat in a booth near Clyde’s sister, Allison Strope, and her friends. They got some drinks—Justin bought a Bud Light and a few shots of tequila, Clyde ordered her usual strawberry margarita. But they didn’t stay for long.

A review of thousands of pages of court filings and trial transcripts, interviews with Justin, his parents, and Clyde capture what happened next.

Justin, already in a sour mood because he had work early the next morning and had not wanted to go out in the first place, became irritated by a man in Strope’s friend group who he believed had made an inappropriate comment to Clyde. He got in an argument with Clyde and, seeking to avoid a fight with the man, decided to head home for the evening.

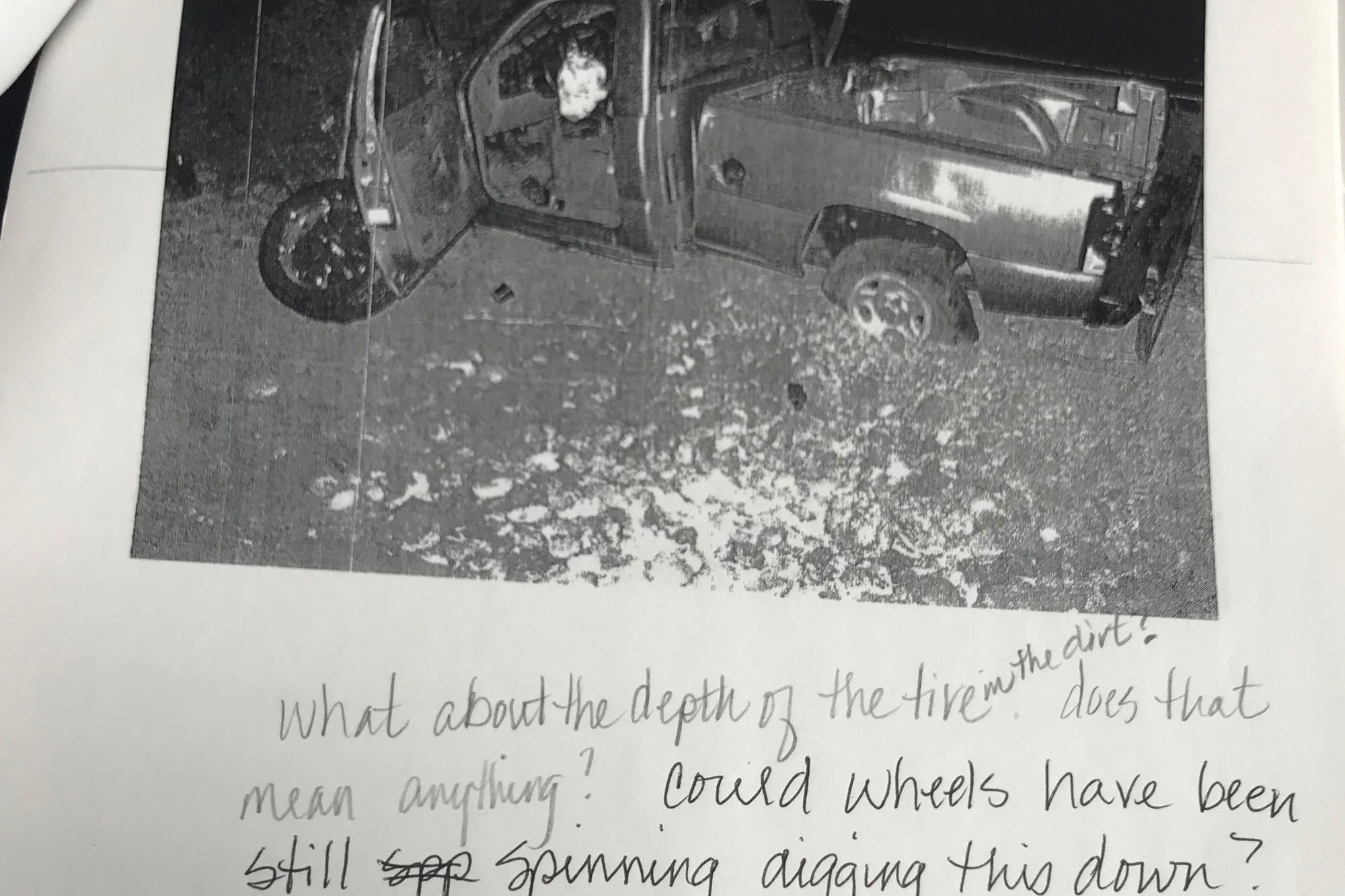

He got into his 2003 Chevy Silverado, pulled out of the parking lot, and headed west on Bell Road. He turned onto 43rd Avenue heading south and says he began fiddling with the CD player as he approached the intersection at Greenway Road. He then sped through the intersection, colliding with two other vehicles.

Two older couples were inside the cars, and everyone was seriously injured. Silvestro Ferrantello, 66, and his wife, Rosa Ferrantello, 62, were ejected from their vehicle by the force of the crash. Clemont Vigliotti, 65, whose Chevy Malibu was struck by the Ferrantellos’s Chevy Tahoe after Justin’s truck knocked into it, and his wife Lenna Vigliotti, 61, were also badly injured. None of the people involved in the accident remember what happened. All four were transported to the hospital in critical condition, each with fractures, lacerations, brain injuries, and broken teeth. Two of the victims were in comas for a few days.

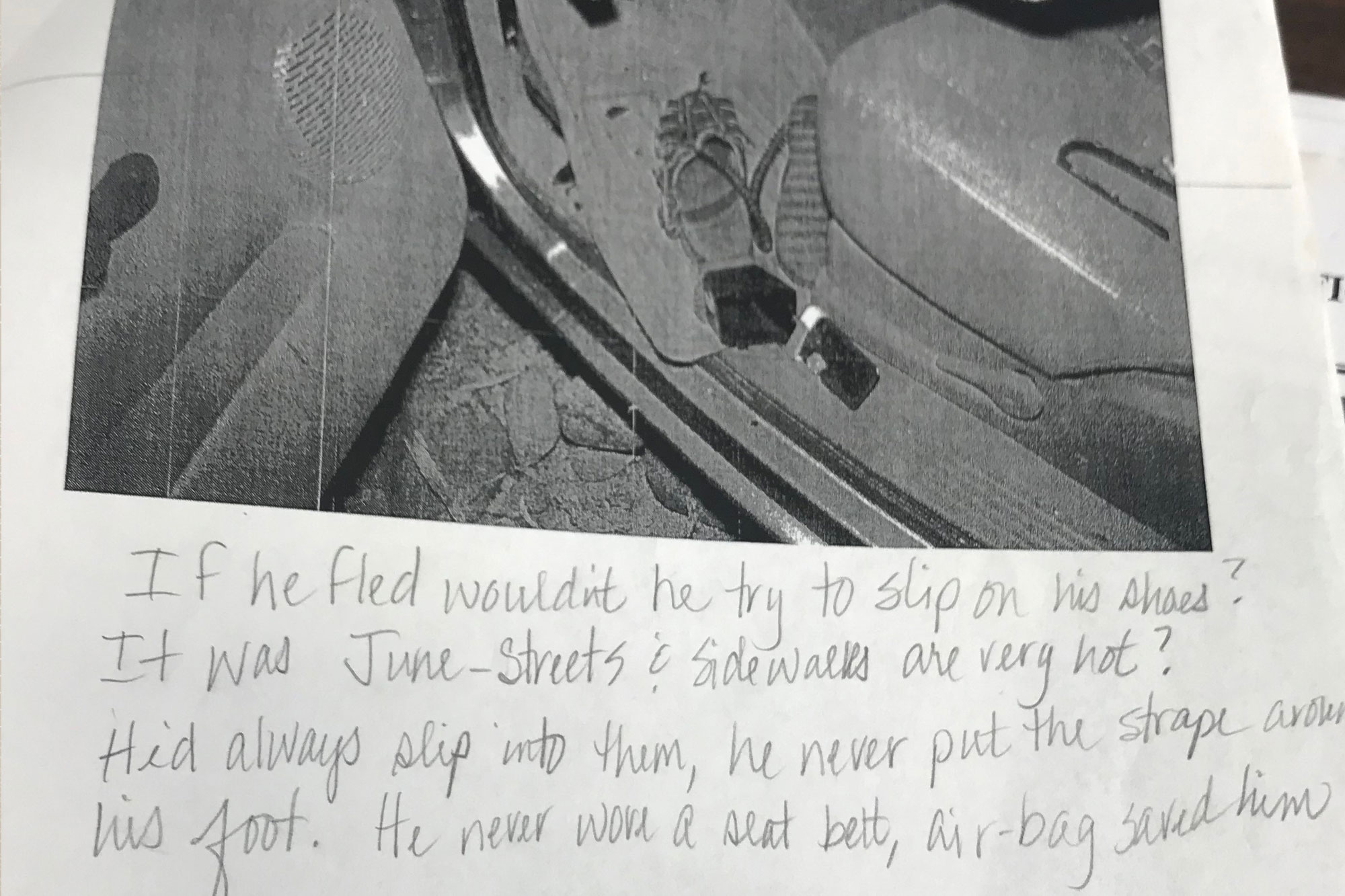

Several witnesses, passersby, and neighbors called 911 immediately. One woman who witnessed the crash walked over to Justin’s Chevy. The door was open. His sandals and keys were still in the vehicle, but Justin was gone. There was blood on the airbag and on the gravel just outside the driver’s side door.

Clyde, who had left the bar with her sister out of concern for Justin shortly after he left, arrived at the scene of the accident around the same time the first police officers showed up, she told The Appeal. Worried for Justin’s safety, Clyde immediately called Justin’s mother and told the detectives everything she knew. Justin’s father, Chuck Dixon, headed to the scene of the accident as well.

Phoenix police say Justin hid from them until all was clear. But Justin’s father and Clyde, who were at the scene of the crash for roughly five hours that night, say they did not see police searching for Justin, despite their frantic pleas to find him.

Police cordoned off the scene. They interviewed witnesses, photographed the wreckage, and took measurements to reconstruct the collision later. Detective Doug Opferbeck was lead investigator on the case. Later, Opferbeck and two other Phoenix police officers would testify that they searched for Justin for about five to 30 minutes before giving up.

“I was there, they weren’t looking for Justin,” Clyde told The Appeal. “They could have found him if they looked.”

According to the police, a man who lived in a house near the intersection saw someone matching Justin’s description scaling a fence near his property. He did not pursue the person, and during his trial testimony, Opferbeck said police did not pursue based on the lead at the time because the information was given later. Police later found a shirt with Justin’s blood on it in a shed a few hundred feet away from the scene of the accident.

After he woke up later that morning, Justin began walking home, shoeless and covered in blood. Clyde’s eldest sister, Lynda Clyde, happened to be driving down Thunderbird Road at the time when she spotted Justin. She drove him back to her parents’ home, where he and Clyde were staying.

Clyde told Justin the police were looking for him and asked if he’d be all right with her calling the detective. Justin said yes. They contacted the police and Justin’s parents, then Clyde brought Justin to a hospital. He was evaluated for his inability to recall the incident, headache, loss of consciousness, nausea, vomiting, head trauma, road rash on his shoulder, and an abrasion on the back of his head. His blood alcohol level was zero, but by the time he was tested, more than 12 hours had passed since the accident. Chuck and Sheila met Justin there. It would be the last time either of them saw their son outside as a free man.

Opferbeck talked to Justin’s parents at the hospital, then went into Justin’s hospital room to interview him. Justin answered the detective’s questions and acknowledged that he had a few drinks at Valle Luna. Justin cried several times throughout the interview, particularly when Opferbeck told him how badly injured the people he struck were.

Opferbeck told Justin he was at fault for the accident. Police transported Justin to jail. He’s been locked up ever since.

It took over a year for Justin’s case to go to trial. A judge ordered him held on a $100,000 bond. His public defender got it down to $65,000, but it was still far more than Justin’s family could afford. Sheila tried to put up her house as collateral, but it didn’t have enough equity, so they couldn’t make bond.

After the accident, Justin turned down a plea deal. “He knew he was facing an astronomically and disproportionately high sentence if convicted at trial,” the attorney his family hired for him wrote in a sentencing memorandum. But he refused to admit guilt for something he maintained he did not do: commit aggravated assault.

He had reason to be hopeful—Clyde and Chuck said a witness they spoke with that night said she didn’t think Justin had run the red light. But by trial time, that witness said she had time to process what had happened and that Justin had run the light.

“If we could have seen into the future we could have signed the plea deal,” Clyde told The Appeal. “If only we would have known. He would have signed it. And this would be over. But he didn’t. When they got that plea deal, it was just a couple months in. … We were all still in the same boat of thinking there’s witnesses that said he didn’t run the red light. We just thought, why would you take 10-12 years when there’s witnesses that said you didn’t do it?”

As the state readied for trial, Justin repeatedly vented his frustration at the sentence he was facing on recorded jailhouse phone calls to Clyde and his loved ones. Later, the prosecution would play select moments from the hundreds of hours of tapes in an attempt to paint Justin as a remorseless, rage-filled danger to society.

Vince Goddard, one of the prosecutors, also used the tapes to pit people in Justin’s life against each other. Clyde said Goddard repeatedly contacted her sister, Allison Strope, before the trial. Strope was a witness to the events at Valle Luna and the crash scene, and she had animosity toward Justin because she did not think he treated her younger sister well, according to testimony from Strope and Clyde during Justin’s trial. According to Clyde, Goddard repeatedly played recordings of personal phone calls between Clyde and Justin for Strope—often making her listen to them argue—in an effort to ensure that her testimony against him at trial would be especially damning.

Clyde says Goddard tried to get her whole family involved in the trial, despite the fact that only she and Strope had direct knowledge of the accident.

“To me, what Goddard did was just shady and immoral,” Clyde said. “There was no reason to do what they did. It wasn’t right. They influenced her.”

Goddard did not respond to emails seeking comment.

When it came time for Justin’s trial in September 2006, Sheila couldn’t sit in the courtroom. Goddard and Adel had named her as a witness, so she was not allowed to be present for the proceedings. So every day, she sat on a bench outside Justin’s courtroom with a sign that read “I’m Justin’s Mom.” The state never called her.

“They didn’t want the jury to see Sheila crying,” Chuck told The Appeal.

“So now these people think, if a mother won’t even be there for her child, how bad is this person?” Sheila said.

Though they felt that Justin was not getting much help from his public defender, his parents couldn’t afford a high-powered defense attorney. In February 2006, Justin’s original public defender withdrew from the case after Justin and Sheila filed bar complaints against him. Justin’s parents managed to hire a private attorney to join the case shortly before it went to trial, but she could not take an active role during the proceedings. By the time she joined on, the prosecutors had already filed successful motions to exclude certain evidence from trial that might have been helpful to Justin’s defense, while also making sure that their evidence, witnesses, and experts would be admissible before the jury.

Justin’s lawyer would “come in and laugh with the prosecutor every time they walked into that courtroom, talking about golf,” Sheila said, referring to her son’s second public defender, Randall Craig.

Reached by phone, Craig said he does not remember much about the case, and facing complaints from defendants and their loved ones goes with the territory. He said he thought Justin’s sentence was harsh and noted that Arizona law allows for especially harsh sentences. Asked about the criticism that he often walked into the courtroom joking and talking about golf with the prosecutor, Craig said he doesn’t golf and “I wouldn’t do that.”

Goddard used his opening remarks to present the state’s evidence narratively and persuasively, setting a scene for the jurors and doing his best to evoke an emotional response, trial transcripts show. In contrast, Craig repeatedly stated that the jurors would be convinced “when you listen to the evidence” that it was a tragic accident.

Goddard and Adel essentially argued that Justin was in a rage when he left Valle Luna that night and used his car as a weapon simply because he was angry and reckless. Based on measurements taken at the scene, the Phoenix Police Department calculated that Justin was going at least 68 miles per hour in a 40 mph zone, Opferbeck said during the grand jury proceedings.

But by the time they went to trial, that number had ticked up to 71, then again to 94. In his testimony, Alan Pfohl, a detective with the police department’s Vehicular Crimes Unit, said his initial reconstruction of the collision determined that Justin must have been going 71 mph. But as he was preparing to testify, Pfohl said, he double checked his math and determined that Justin must have been going at least 94 mph.

Pfohl also said his investigation showed that Justin made an evasive action as his Chevy neared the older couples’ vehicles.

Marks left by the Silverado in the road indicated that “it would be a safe assumption,” Pfohl said at trial, “that the driver of the Silverado attempted not to hit whatever oncoming traffic.”

An expert witness paid for by the state, Rusty Haight, testified that black box data collected from the vehicles involved in the crash showed that Justin was going about 96 mph.

Craig did question the police department’s changing math, though he did not call in his own expert to contest the reliability of black box data. The co-counsel who Justin’s family retained just before trial filed a motion to prevent the black box data from being used, alleging that it “lacks sufficient reliability” and raising concerns over the possibility that it could erroneously read the rate of speed. But the prosecutor contested it and the motion was later withdrawn.

At the trial, Goddard asked the state’s expert witness if there was “anything that led you to believe that there was something wrong, like a vehicle recall, something at all wrong with any of these cars at any point for anything you looked at?” The witness said no.

But two years later, in 2008, a class action settlement was awarded to owners of certain GM vehicles with defective speedometers, including 2003 Chevy Silverados.

“This letter is intended to make you aware that your vehicle could develop a condition where one or more of the instrument panel gauge needles may stick, flutter, or become inoperative,” a letter from Chevy to Sara Clyde, the registered owner of the Silverado, read. “This may cause inaccurate readings, including the speedometer and the fuel gauge.”

After a weeklong trial, the jury found Justin guilty on all six counts. Three months later, in December 2006, Justin’s parents, grandparents, brothers, girlfriend, aunts, uncles, and friends pleaded with the court to be reasonable, to see that Justin had made a mistake but didn’t deserve to have his entire life taken away for it.

When Sheila went before the court at Justin’s sentencing hearing, the first thing she did was turn around and apologize to the victims. “Please understand,” she said, turning back around to address the judge, “he was 21 years old. We all make mistakes at that age. I don’t think he deserves to be put away for the rest of his life. … He has a three and a half year old beautiful daughter who deserves her to have her daddy … but she may never know [him].”

The family’s pleas fell on deaf ears. Judge Aimee Anderson decided Justin’s age, child, and lack of intent were not mitigating factors. And the jury found six aggravated factors had been proved in the case, allowing the state to seek an enhanced, or increased, sentence under Arizona law.

Justin’s prior felony convictions also contributed to his harsh sentence. One conviction was for an attempted burglary he was accused of committing when he and a girlfriend entered her parents’ house without permission with the intention of taking and selling tools. (He was 17 at the time, but the county attorney’s office chose to charge him as an adult.) The other was for drug possession. At the time of the accident, Justin was on parole, and the court also held his history of getting into trouble for using marijuana as a teenager against him.

“During [your daughter’s] short life, you have been in prison, on parole, and then these charges came down approximately 18 months ago,”Judge Anderson said at Justin’s sentencing. “Perhaps, Mr. Dixon, you never learned that anybody—any man can be a father, but it takes somebody very special to be a daddy, and you’re not that special.”

Anderson then sentenced Justin to 51.75 years: 20 years, concurrent, for counts one and two (two aggravated assault charges stemming from hitting one of the two vehicles); 20 years concurrent for counts three and four (the aggravated assault charges for the second vehicle), to run consecutive to the sentence for counts one and two; 11.25 years for leaving the scene of the accident; and six months for reckless endangerment.

Rosa and Silvestro Ferrantello did not respond to phone calls and emails seeking comment. Neither did Clement or Lenna Vigliotti.

Asked if she could recall the moment when she heard Justin’s sentence for the first time, Sara Clyde began to cry.

“It was unbelievable and I just didn’t know what to do,” she said. “I just couldn’t imagine that situation and how they could determine he could deserve that much time for what happened. I loved him, and the thought that he was never gonna be out again—and we were so young—I just couldn’t—” Clyde said, holding back tears. “It was heart-wrenching. You just couldn’t imagine. I just couldn’t believe that they were giving him this much time for what happened. I understand you have to do your time, but I don’t think that time was equivalent for what happened. I’ll never understand it. And it hurts so bad.”

Justin tried to appeal his sentence, but he wasn’t successful. In October 2008, a deputy legal advocate filed an appeal stating that he “received an excessive sentence.” But the judge disagreed. In a supplemental brief, Justin argued that his defense counsel was ineffective. But the appeals judge was not convinced of that or of any of Justin’s other arguments. Justin’s appeal was denied.

His family later tried again and paid an attorney $10,000 just to read the trial transcripts, but when the attorney was done, he said it would cost tens of thousands of dollars more just to begin the process, and even then, he couldn’t guarantee the appeal would get Justin out.

Justin could also apply for clemency, but Arizona’s clemency board is reluctant to grant requests, and Governor Doug Ducey has failed to approve clemency even for people who are on the brink of death and whose commutations have been unanimously approved by the clemency board.

Sheila stopped collecting articles. It was too depressing. But she still holds on to the hope that she may see her son outside of prison again one day, before he’s 70. Now, with the pandemic surging in Arizona’s prisons, particularly in the facility where Justin is held, his parents feel a renewed urgency to get their son out.

To Sheila, and Chuck, and Clyde, there was nothing fair or just about Justin’s sentence.

“They wanted that notoriety, those headlines, of the longest case,” Chuck said. “I never thought he could get that kind of a sentence. … It’s a life sentence.”

“The whole thing was just a disaster from the beginning,” said Clyde. “I just feel like that detective and that prosecutor were on a mission. … [Goddard] wanted to make it sound as bad as he could so that he could get the longest sentence, so he could look good. We heard him tell somebody that he was going to get the longest sentence ever handed down for something like this. It was like a challenge. And he was proud of it. And I don’t think that’s justice.”