Political Report

Governor’s Race Could Decide If Louisiana’s Prison Population Continues to Shrink

Louisiana shed its status as the top incarcerator in the county last year, but the trend is fragile.

Louisiana shed its status as the county’s top incarcerator last year, but the trend is fragile.

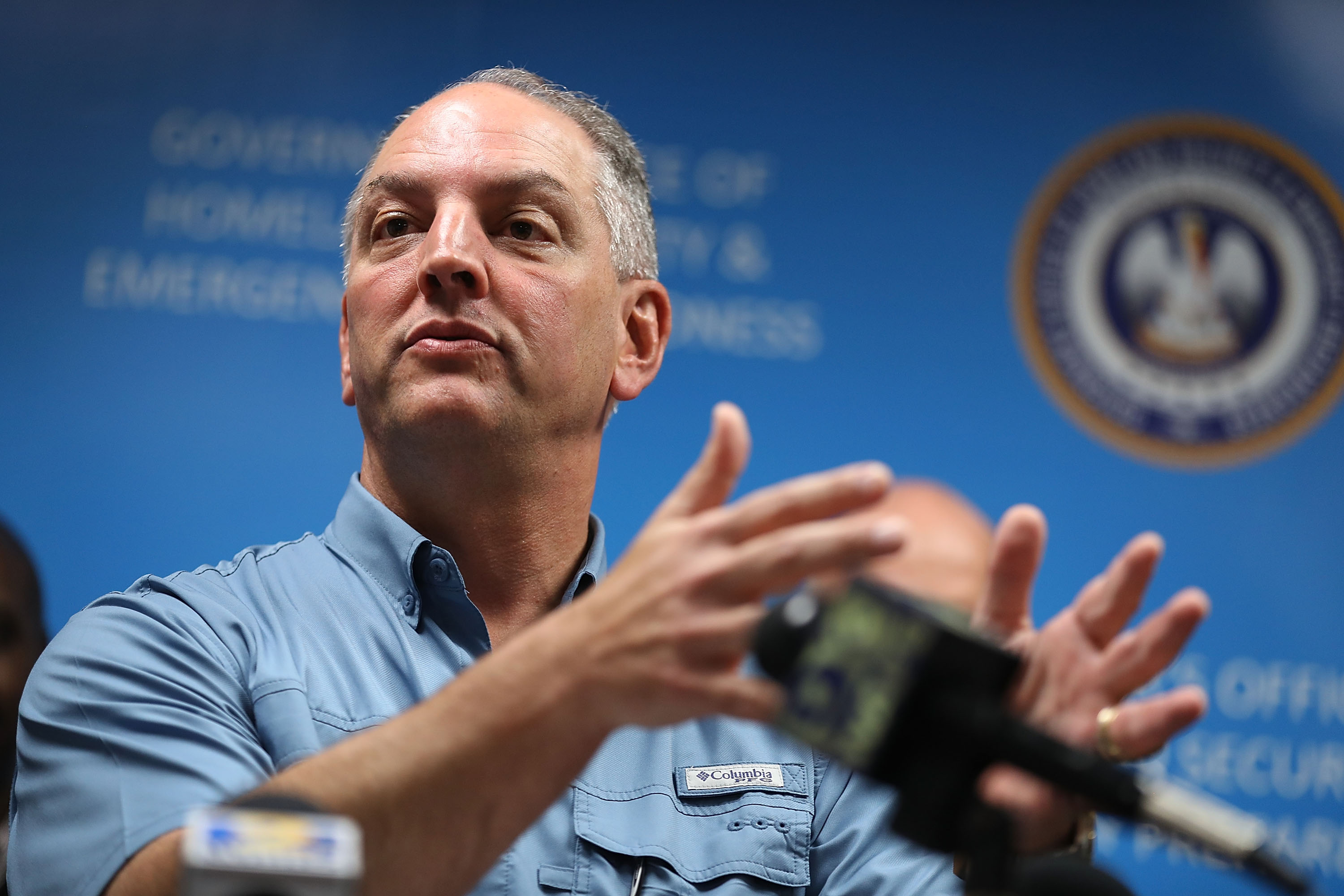

Louisiana overhauled its criminal legal system in 2017 and soon shed its status as the country’s top incarcerator. That year, a package of sweeping reforms expanded alternatives to prison and reduced mandatory minimums. The Republican legislature adopted these measures by large majorities, and Democratic Governor John Bel Edwards then signed them into law.

Despite this bipartisan pedigree, some of the state’s most prominent Republican officials are foes of criminal justice reform and use them to attack Edwards, who is up for re-election this fall. One of his main challengers, GOP Representative Ralph Abraham, is running firmly against the policies, which he says have “opened the gates” to crime.

This election will shape the viability of further criminal justice reform over the next four years.

Louisiana’s legislature passed new measures this year, albeit smaller ones, and advocacy groups are championing more bold changes to overhaul the state’s reliance on incarceration.

“Ten years ago, five years ago, you went to that statehouse, you talked about the people who were incarcerated and formerly incarcerated, and the tone was very negative. Now, we hear a very different tone,” Bruce Reilly, deputy director of Voice of the Experienced, an organization that advocates for criminal justice reform in Louisiana, told the Political Report. “The really positive part is how many people have come on board.” Reilly credits the advocacy of formerly incarcerated people, which his group champions, for changing the narrative.

A governor opposed to these shifts could use his veto pen to block new reforms, or pressure lawmakers to roll back existing ones.

Louisiana’s 2017 laws reduced the magnitude of incarceration in the state. Its prison population dropped by 19 percent between 2012, when it peaked, and 2018, according to a state report on the laws’ impact after a year in effect. This drop was fueled by a cut in the use of habitual offender enhancements, which provide harsher penalties for people with prior convictions, and in the length of sentences for drug convictions.

The same report found that this has saved $12 million originally allocated to incarcerate people. Louisiana is reinvesting the majority of those funds into programs meant to serve as alternatives to prison or to facilitate re-entry.

That said, sentencing schemes remain very harsh. Even the reduced 2018 incarceration rate was far higher than the national average: 50 percent higher, according to the Prison Policy Initiative.

And the number of people incarcerated in Louisiana is climbing again this year because ICE is contracting with local law enforcement to use now-vacant jail space to detain immigrants.

Still, Abraham is staking his gubernatorial bid on warnings that even the most consensual of criminal justice reforms threaten public safety.

In December, he opposed the final passage of the First Step Act, the federal law that decreased lower-level sentences and curbed mandatory minimums. Three of Louisiana’s four other Republican representatives voted for it, but in voting against it Abraham invoked his home state. “We’ve seen the negative effects this kind of criminal rights activism is having in Louisiana, and I’d hate to inflict that mistake on communities elsewhere in our country,” he said in a statement. Neither his campaign nor his office answered a request for comment on which specific reforms he opposes, and on what negative effects he sees.

His words echo a 2018 op-ed written by U.S. Senator John Kennedy and state Attorney General Jeff Landry, who cite two cases of recidivism as their evidence for the ill effects of Louisiana’s reforms, a familiar strategy that Adam Johnson of The Appeal has dubbed “emotionally charged anecdotes and a lack of meaningful statistics.”

“Before the ink was barely dry, critics of the reforms began denouncing them with overinflated claims and anecdotal evidence,” Daniel Erspamer, chief executive of the Pelican Institute, a conservative think tank that supported the 2017 laws, told the Political Report.

“While it’s certainly too early to claim ultimate success or failure, the actual data suggests progress in reducing crime and recidivism while saving scarce taxpayer dollars,” he added, pointing to early data that finds that the rate of reincarceration is lower than it was before the laws went into effect.

Reilly also warned about punitive rhetoric. “The Willie Horton ad worked, people are going to use the strategies that will get them the most votes,” he said.

But Edwards, unlike Abraham, describes reform as a boost to public safety. “Just like we did in Louisiana, Congress has … recognized that what this country is doing, as it relates to criminal incarceration, just hasn’t been working,” he said in a statement after the passage of the First Step Act. “We have been spending too much money on a system that is broken, and our communities have not been any safer for it.”

Edwards’s other main challenger is Eddie Rispone, a Republican businessman who has not taken a clear public position on the 2017 criminal justice reforms. His website does not have an issues page as of this week, and his campaign did not answer a request for comment.

Other matters related to the criminal legal system are also occasioning contrasts. Edwards used his clemency powers more frequently than his predecessors, though he slowed down the pace in the latter part of his term, The Appeal reported last year.

He also expanded the state’s Medicaid program shortly after becoming governor. Medicaid expansion can alleviate patterns of reincarceration by improving access to treatment for people with addiction and mental health issues. Abraham and Rispone have both sharply criticized the program, but have stopped short of saying they would fully rescind Edwards’s executive order.

The rapid growth in the detention of immigrants looms large as well. Counties throughout the state are entering deals to rent their jail space for ICE to detain immigrants it arrests elsewhere. And they reap substantial financial benefit. ICE pays counties considerably more money for detaining an immigrant than the state pays them for incarcerating someone with a criminal conviction, according to the Times-Picayune.

Both Republicans say they would support or accelerate this trend. Rispone took out a full-page ad in the Times-Picayune in July to proclaim his alignment with the White House on the issue. “When I’m governor, Louisiana will stand with President Trump to protect ICE, build the wall, and end illegal immigration,” the ad says. “We’re getting tough on illegal immigration the second my hand comes off the Bible.” And Abraham says he would look to further enshrine cooperation with ICE via legislation to override local efforts to restrict it. The Edwards campaign did not respond to a request for comment on his views regarding local cooperation with ICE.

“This state is very willing to lock up as many immigrants as will come our way, and the progress we made in decarceration has been erased,” Reilly of Voice of the Experienced said.

And he added, comparing this dynamic to the federal incentives that drove punitive laws in the 1990s: “People who didn’t want to be the number one incarcerator in the country have shifted their tune now that there are federal dollars behind it.”