The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative Funds Clean Slate Policy. So Why Won’t Facebook Take Down Mugshots?

Mark Zuckerberg could engage in criminal legal reform by bringing Facebook’s policies in line with CZI’s mission and allow people to request that their mugshot be taken down.

With the U.S. officially in a recession after coronavirus lockdowns, jobseekers face competitive and uncertain prospects. But for millions of Americans, the thought of being screened by potential employers brings a renewed sense of terror; surveys show that 70 percent of employers use social media to screen applicants.

For the 1 in 3 Americans with a criminal record, social media can be a hostile and humiliating place, where an old mugshot or arrest log that remains posted on a police department website or Facebook page appears when their name is searched. For many, it’s tech platforms like Facebook and Google that cause anxiety during job-seeking—not the background check that comes with an employment offer. Official background checks are regulated by the Fair Credit Reporting Act, and although they routinely report incorrect information, an applicant is allowed to see the report and dispute errors. No one knows when a prospective employer or landlord is searching for them on Facebook.

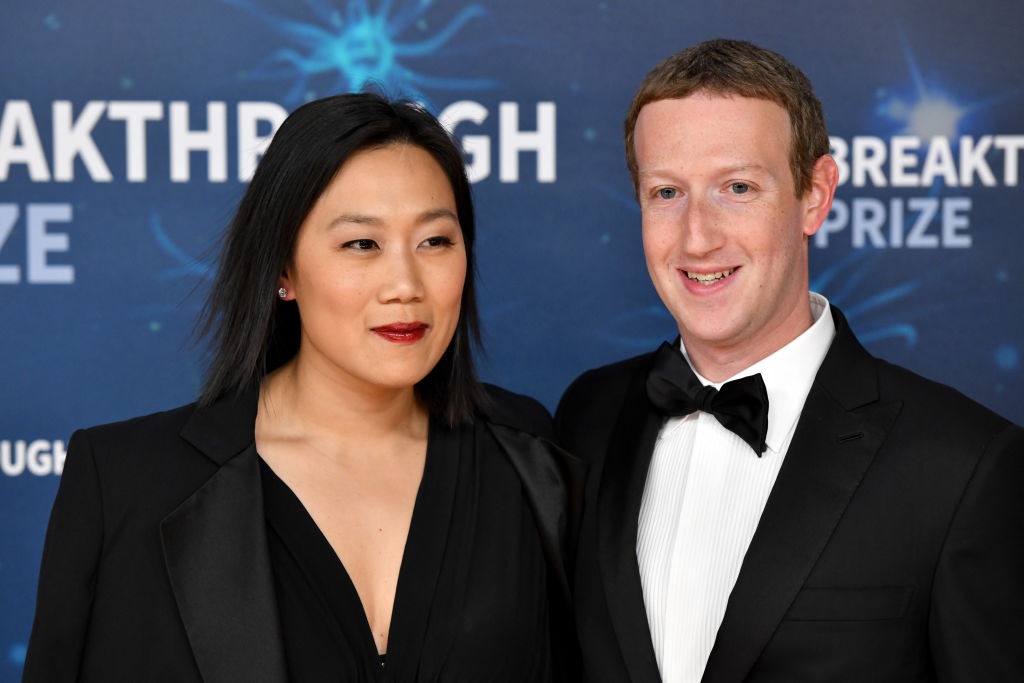

Ironically, the huge problems caused by mugshots on social media come as tech companies and their philanthropic arms have never been so involved in criminal legal reform. These companies advocate for hiring and training formerly incarcerated people and developing algorithmic approaches to foster rehabilitation and second chances, such as through automated record expungement. The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI), a limited liability company established and owned by Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and his wife, Priscilla Chan, promotes a criminal justice reform agenda focused on “providing fair chances for those impacted.”

CZI is also a key funder of the Clean Slate Initiative, which advocates for the use of technology to seal criminal records in an effort to thwart discrimination based on a person’s history in the criminal legal system. These are laudable efforts, but Clean Slate faces the troubling reality that criminal records remain on the internet long after expungement.

So why does Facebook allow users to post mugshots?

Raj, who was arrested in Maricopa County in 2008 after a dispute with his girlfriend, exemplifies the harm. The court later sealed his arrest record and Raj moved on with his life. About a decade later, however, his mother, who lives in India, searched for him on Facebook and found his mugshot. His aunt called him at 2:30 a.m., saying, “There’s a picture of you arrested on Facebook. Do something. Get that picture off.”

“They were so terrorized,” Raj said. He was, too. “Every relationship I’ve had and every action I’ve wanted to take—this is something that has held me back. This has changed me as a person. For the longest time I didn’t want to date, I didn’t want to meet people. I didn’t want a recruiter or employer to see my name.”

Mugshots attach criminal stigma to people who were arrested but not necessarily convicted of a crime. This means legally innocent people have their mugshots easily retrievable through searches for their name on social media platforms. Arrests are unevenly distributed by race, mental health, and social class, so mugshots exacerbate these inequalities. Even if a person is convicted, these photos linger online long after they’ve left prison or jail.

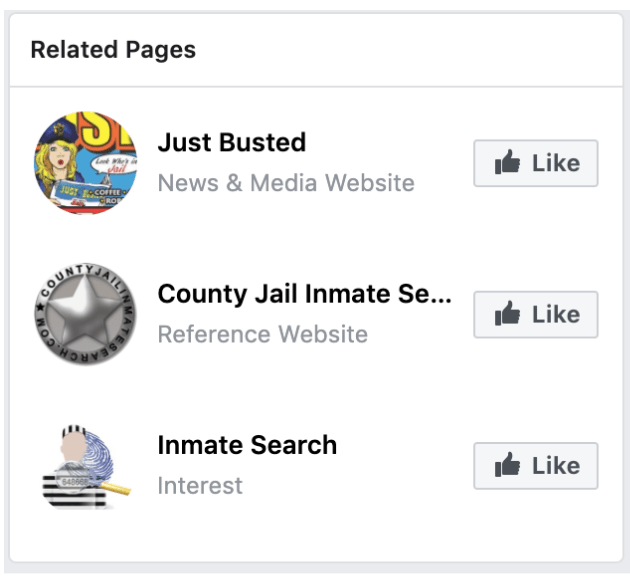

Mugshots are often posted on Facebook by police departments to show communities the work they’ve been doing. These mugshots are shared and reposted by users and local newsrooms, as well as predatory extortion websites. Some argue it’s a public safety measure. Others say it’s a way to watchdog the police. Critics and even an online petition by the Movement Alliance Project have criticized Facebook for allowing mugshots—and the ugly and racist commentary that often accompanies them.

Posting mugshots on social media doesn’t break any laws. First, it’s legal to post public records on private websites, including the mugshots of people who were not convicted of a crime or have had their records sealed. Second, Facebook operates under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, a policy that protects tech platforms from lawsuits based on content posted by their users. So, when local police and regular people post mugshots, no one is held legally responsible for the harm it causes. And in contrast to Twitter, Zuckerburg has recently maintained that Facebook should take a hands-off approach to content moderation, even when it is misleading or inflammatory.

Because this isn’t a legal or regulatory issue, it is a question of company policy.

Currently, Facebook’s lack of content moderation undercuts Zuckerburg’s efforts at criminal legal reform. Although CZI’s efforts to teach incarcerated women how to code have merit, these same women will have to face the existence of their criminal record on social media as they seek employment. Allowing them to request that the content be removed after they complete their sentence, for example, would provide an opportunity for a true clean slate.

Zuckerberg could engage in direct, meaningful criminal legal reform by bringing Facebook’s policies in line with CZI’s mission and allow people to request that their mugshot be taken down. Such a request could even fall under existing company policy for removal of “cruel and insensitive” objectionable content. A Facebook policy change that removes outdated arrest records, old convictions, or expunged records from the social media platform is an efficient, direct, and far-reaching reform for the criminal legal system.

Facebook and CZI did not respond to requests for comments on policies regarding a person’s ability to remove their mugshot.

Other private sector players have stepped up. Newsrooms have tackled the question of how to balance their need for advertising revenue generated through mugshot clickbait against the damage caused by a mugshot. In February, the Houston Chronicle announced that it would no longer publish mugshot galleries; on Tuesday, Gannett, the largest newspaper company in the U.S., stopped publishing mugshots on the websites of former GateHouse newspapers (GateHouse and Gannett merged in 2019). Some police departments have simply ended the practice of posting mugshots on their Facebook sites, acknowledging that although it’s legal, it’s not necessary.

Second chances—from an arrest that never led to criminal charges to a long-ago conviction—don’t begin and end with narrow criminal legal system policy interventions. The stigma of criminal records seeps into everyday life. If big tech wants to be involved in criminal legal reform, it might consider how its enormous resources and considerable power could be used to limit discrimination in the era of mass incarceration.

Sarah Esther Lageson is an assistant professor in the School of Criminal Justice at Rutgers University-Newark. She is the author of “Digital Punishment: Privacy, Stigma, and the Harms of Data-Driven Criminal Justice.”