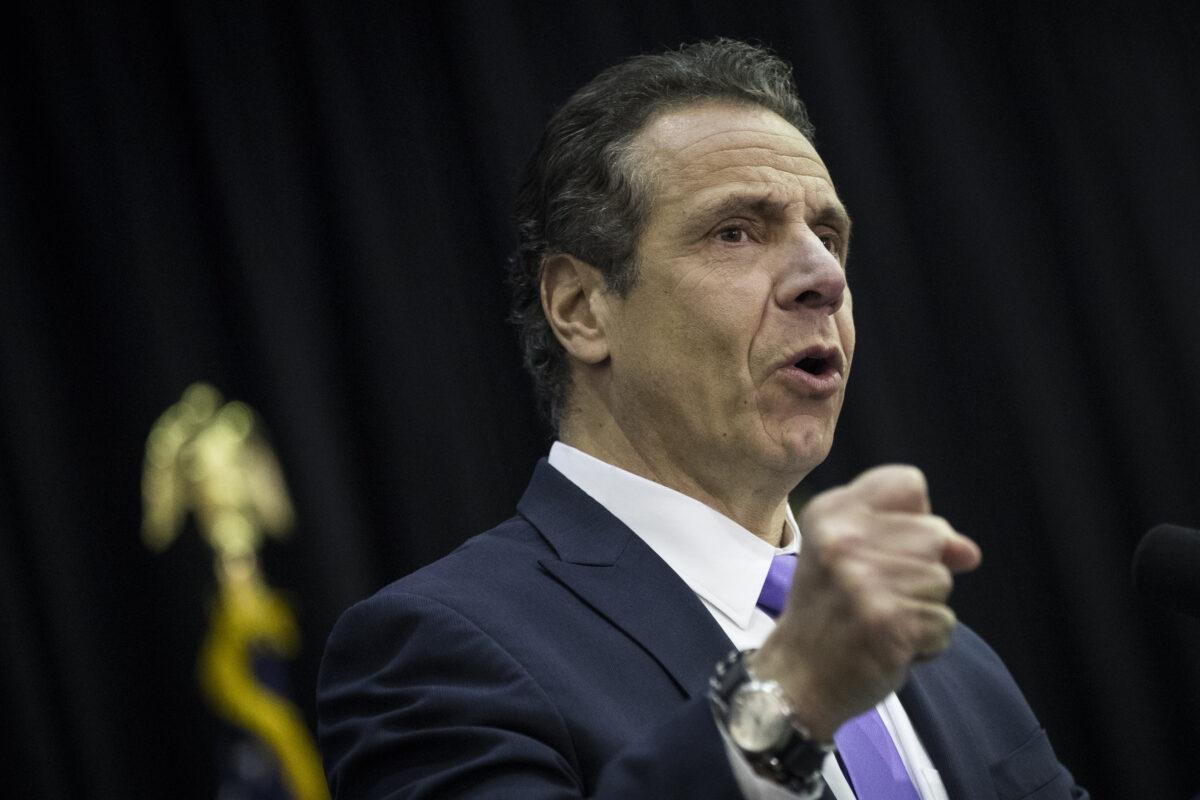

Will Governor Cuomo Give Roy Bolus a Second Chance?

Bolus is one of thousands of New Yorkers sentenced to life in prison who are waiting for the governor to keep his clemency promise.

In 1988, when Roy Bolus was barely 18, he was arrested in connection with the murder of two men during a robbery in Albany, New York. Despite never having fired any shots, Bolus was convicted of felony murder and is serving the 30th year of an 80-years-to-life sentence. He will not be eligible for parole until 2068, when he’s 98 years old.

When Bolus heard in 2015 about Governor Andrew Cuomo’s creation of an Executive Clemency Bureau to help identify incarcerated people in New York State who could be eligible for a pardon or reduced sentence, he assumed it just wasn’t for him.

“The case, being a violent case … I just thought this would be something where the governor and the clemency bureau would just say ‘nah,’” Bolus explained over the phone from Green Haven Correctional Facility in Albany. “They wouldn’t even look at me.”

But in December 2016, when Bolus heard that Cuomo had granted clemency to Judith Clark, the political activist who acted as a getaway driver in a 1981 robbery involving three homicides, he realized he had a chance. “I was like, ‘Oh shoot, if that can happen for her, that can happen for me. I’m going to give it a shot!’” Bolus recalled.

There are two types of clemency: pardons, which expunge past convictions, with or without added conditions, and commutations, which release current prisoners or shorten their sentences.

Yet the road to clemency in New York State has been a slow one under Cuomo. Since taking office in 2011, the governor has granted only 12 commutations, and just two in 2017.

Cuomo’s office is quick to point out that he has pardoned dozens of immigrants facing deportation, conditionally pardoned scores of people convicted of crimes when they were under 18, and restored voting rights to thousands of parolees. But advocates say the slow pace of commutations raises questions about Cuomo’s commitment to clemency.

“When you announce a clemency initiative and you raise hopes and expectations, frankly it’s cruel to not actualize it,” said Steve Zeidman, director of the Criminal Defense Clinic at the CUNY School of Law, which is currently helping about 25 people with clemency applications and worked with Judith Clark on her application. “Multiple people on the inside have told me that false hope is worse than no hope at all.”

For people like Bolus, who were incarcerated at a young age and have spent most their lives inside maximum security prisons, clemency represents their best chance to ever experience the outside world again.

A new focus on clemency

Criminal justice reformers have increasingly focused on the power of clemency as governors nationwide look to reduce their states’ prison populations. New York State, which began its decarceration project in the early 2000s, well before other large states, had the biggest reduction in prisoners in the country from 2000 to 2010, as the state drastically altered how it dealt with nonviolent offenders. After hitting a high of 72,899 prisoners at the end of 1999, that number dropped to 55,436 by late 2011. But since then, New York State has “hit a wall,” says Fordham University law professor John Pfaff. Over the last seven years, it has been able to reduce its prison population by only approximately 6,000 people. That’s largely because the state hasn’t changed the long sentences consistently meted out to those convicted of violent crimes.

“New York has a lot to be proud of,” Pfaff told The Appeal. “But the decline is going to stop until we start turning to violent offenses soon. And the decline is going to stop at a population that was much higher than it was in the late ’70s and early ’80s.”

That’s where clemency comes in. It offers hope to people like Ray Bolus who have decades left on their sentences before they are even eligible for parole. (Judith Clark was granted a parole board hearing 40 years before she would otherwise be eligible; the board denied her parole at her first hearing in 2017.)

Cuomo created the Executive Clemency Bureau to identify individuals who had “made exceptional strides in self-development and improvement,” seeking to reinvigorate and streamline the process, which was little used in his first term. Cuomo did not issue a single clemency during his first two years in office, and applications for clemency in New York State dropped from 1,269 in 2010 to 171 in 2014. Now, with law firms devoting pro bono assistance worth millions of dollars, and nonprofits agreeing to handle hundreds of clemency applications, those application numbers have begun to climb—even as the number of actual commutations has barely budged.

Critics say that’s because of the guidelines Cuomo set when he introduced the clemency board, requiring, for instance, that a prisoner has served at least half of his or her minimum prison term, and is not eligible for parole within a year of the date of the application for clemency. That eliminates both people serving extremely long sentences, like Bolus, who has yet to complete half of his sentence, in addition to people who have exceeded their minimum sentence but are repeatedly denied parole.

As Mariame Kaba, a founding member of Survived and Punished, a network that works with criminalized and imprisoned survivors of gender-based violence, told The Appeal’s Victoria Law in June, “We are perplexed by the rules he set for himself. They’re incredibly narrow and leave out an incredible number of people.”

Asking the state to rethink how it deals with violent offenders is the next frontier in criminal justice reform and New York’s decarceration project, explains Zeidman of the Criminal Defense Clinic.

“These people have been essentially sentenced to die in prison,” he said. Zeidman flips through a binder, showing the hundreds of letters requesting help he’s received in the three years he’s been working on clemency applications. The letters are primarily from two separate groups of people: those who have been repeatedly denied parole even though they are years past their mandatory minimum sentences, and those still facing decades in prison before they ever see the parole board.

The idea that of the 52,000 people in prison in New York State, there aren’t thousands who, under anyone’s definition of clemency, merit clemency? It’s ludicrous, of course there are.

Steve Zeidman Criminal Defense Clinic

Despite overhauling the application system, Cuomo still lags behind many of his predecessors when it comes to commutations. Former New York Governor George Pataki, a Republican, commuted 32 people in his 12 years in office. Cuomo’s father, Mario Cuomo, issued 37 commutations in 12 years in office. And those numbers pale beside those of former Governor Hugh L. Carey, who granted 155 pardons and commutations between 1975 and 1982, right before New York’s prison population began to skyrocket.

Nationwide, clemency remains a power rarely used by governors, with only 15 states granting frequent and regular pardons or commutations to more than 30 percent of applicants. According to an analysis by the New York Times, New York governors have granted clemency to fewer than one in 100 applicants since 2006, with the exception of David A. Paterson, who granted clemency at a rate of about three in 100.

”There have been precious few clemencies granted,” Zeidman said, in reference to the number of applications submitted under Andrew Cuomo. “The idea that of the 52,000 people in prison in New York State, there aren’t thousands who, under anyone’s definition of clemency, merit clemency? It’s ludicrous, of course there are. I’m seeing them in the letters.”

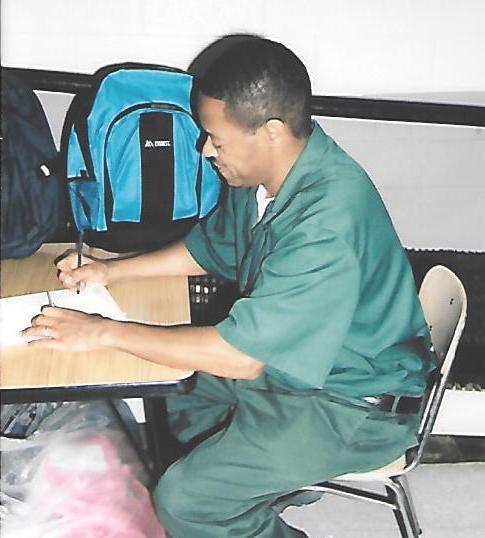

A life in prison

According to his friends and family, Bolus, who grew up in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, has transformed himself over the past 30 years. When he was arrested, he was just a few months shy of beginning college orientation at the New York Institute of Technology on Long Island but had started associating with a group of friends connected to the drug trade. It was an attempt, he has said, to help provide for a young daughter.

Bolus has earned associate’s, bachelor’s, and master’s degrees in prison, and is pursuing a doctorate. It hasn’t been easy for him to access education, either, especially since federal Pell grants were taken away from prisoners as part of the omnibus crime bill signed by President Bill Clinton in 1994. Bolus began creating curriculums for himself and other incarcerated people, becoming a teacher in a program focused on HIV prevention. He plans to continue teaching incarcerated people if he’s granted clemency and eventually paroled, and wants to develop a curriculum that can be taught throughout state prisons.

“Being from the same places that a lot of the other guys in here are from, I understand something that I don’t think the criminal justice system understands about imprisonment and survival and getting out and people being different,” he said. “That’s something that I think society doesn’t have that I have to offer.”

Zeidman is also working on a clemency application for one of Bolus’s five co-defendants, Alphonse Riley-James, who was also sentenced to decades in prison even though he, like Bolus, did not fire a shot. Riley-James and Bolus were with a group of other young men who had traveled from Brooklyn to Albany to rob a rival drug dealer’s safe; during the robbery, two men guarding the safe, George Mosley and William Patterson, were killed. Riley-James was sentenced to 50 years to life and is scheduled to see the parole board for the first time in 2038, when he is 68.

Bolus’s and Riley-James’s sentences came after a spate of “tough on crime” laws passed in the 1970s, as New York pivoted in the midst of rising crime rates from a model focused on rehabilitation to one that focused instead on incarceration. In 1973, New York passed the infamous Rockefeller drug laws, instituting mandatory minimums for drug possession, and in 1978, the state legislature passed new violent offender laws, mandating minimum sentences for certain violent offenses (like felony murder), and limiting plea deals to the specific crimes with which people were charged. To accept a plea deal on a violent felony, for instance, the defendant would have to plead to a violent felony rather than to a lesser charge that might have carried a lighter sentence. The result was a significant rise in the state’s prison population.

What is the upside of [the governor] paroling any sort of risky, high-profile case? He’s not going to get a lot of credit for it, but if something goes wrong, he’ll take a lot of flak.

John Pfaff Fordham University

The fact that Bolus and Riley-James were from Brooklyn but being tried in an Albany courthouse probably didn’t help them gain any leniency in sentencing, reflects Zeidman. County Court Judge Joseph Harris, who ruled on both cases, was known, along with a fellow judge, for harsh sentences.

“They were giving out sentences like popcorn,” Bertrand F. Gould, a former Albany public defender told journalist Jennifer Gonnerman for her 2004 book on the Rockefeller drug laws, Life on the Outside. Gould, who worked in the office from 1968-2000, told Gonnerman that rather than impose minimum sentences for drug crimes, the judges often went for the maximum. Black defendants like Bolus and Riley-James often bore the brunt of that. “It was, ‘We’ll teach those blacks to come up here and sell their damn drugs in Albany.’ … I’m not sure whether it was provincial or racist. Maybe a combination of the two.”

A political calculation

The act of clemency itself comes with certain politicals risks, even if a governor is just shaving decades off a sentence so an individual convicted of a violent offense can see a parole board sooner. The March parole of Herman Bell, the 70-year-old former Black Panther convicted in the 1971 shooting deaths of two New York police officers, set off a firestorm of criticism of the state’s parole board, even from self-described progressive politicians like New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio. The type of controversy that commutations generate might be something that Governor Cuomo, who is thought to harbor presidential ambitions, would want to steer clear of. But he’s currently facing a primary challenge from insurgent candidate Cynthia Nixon, who many observers say has pushed him to the left. By focusing on pardoning those who have already served out their sentences and been released, Cuomo has been able to avoid controversy while improving the lives of formerly incarcerated people.

“What is the upside of [the governor] paroling any sort of risky, high-profile case?” asks Pfaff. “He’s not going to get a lot of credit for it, but if something goes wrong, he’ll take a lot of flak.”

Complicating matters even more is Cuomo’s tight relationship with upstate Republicans, whose constituency relies on the jobs produced by mass incarceration in the state. “If Governor Cuomo were to engage in wholesale clemency, that’s going to shrink prison populations, and what that’s going to do is going to cause prison closures in upstate New York,” Pfaff continued. “You’re going to face tremendous opposition in Albany from Republicans because it will cost them jobs in communities where prisons are often the main driver of employment.”

Nixon has seized on criminal justice as a central issue in her campaign, chastising Cuomo for failing to reform the state’s cash bail system, its rules governing prosecutors, and its approach to law enforcement officers who commit misconduct. In her platform, she also singles out commutations and pardons as an area on which she would differ greatly from Cuomo.

“The Governor has virtually unlimited power to grant commutations,” Nixon said in a statement to The Appeal. “However, he has implemented wholly arbitrary guidelines that severely and needlessly limit people’s access to clemency.”

In her statement, Nixon specifically highlighted survivors of domestic violence as being among those worthy of commutation. “As Governor, I would prioritize pardons and commutations for the sentences of survivors of domestic violence and rape, who were or remain incarcerated for their self-defense,” she said.

Going beyond commutations, Nixon has also proposed permitting the parole board to evaluate all people over age 55 who have served at least 15 years in prison for possible release, even if they have not yet completed their minimum sentences.

He was on the way to college when he made a wrong turn. For that, he’s paid 30 years in prison.

Ada Bolus Roy’s wife

In response to a request for comment from The Appeal, the Cuomo campaign said “the governor has led the way on clemency reform—establishing the state’s first pro-bono clemency program in 2015 [which matches incarcerated people with lawyers offering free help with their clemency applications], taking first-in-the-nation action to grant conditional pardons to more than 100 16- and 17-year-olds, and announcing a landmark pro-bono clemency coalition to expand access to services after Trump disbanded the federal program.” If Cuomo is re-elected, his campaign says “New York will continue to lead the way in ensuring and increasing access to clemency, promoting rehabilitation and creating a fairer, more just New York for all.”

Waiting for mercy

Bolus maintains close relationships with several members of his family, in both New York and North Carolina, and even got married six years ago, while incarcerated, to a social worker who lives nearby in upstate New York. It was his wife, Ada Bolus, who prepared his clemency application, and forwarded it to Zeidman to submit it to the governor.

“He was sentenced to 80 years in prison when he was 18 years old. He was on the way to college when he made a wrong turn. For that, he’s paid 30 years in prison,” Ada Bolus told The Appeal. “His family needs him. Society needs people like Roy. We can give him the second chance that nobody gave him when he was 18.”

Anthony Dixon, who now works helping people recently released from prison find employment, met Bolus in 2009, while they were both incarcerated at Green Haven Correctional Facility. Dixon was serving a sentence of 30 years to life.

“He stuck out like a sore thumb; it was like he didn’t belong here,” Dixon said. ”He had a radiance about him that younger people would look to him. It was just amazing to see people incarcerated for that long have that kind of energy about them.”

Unlike people paroled in their 70s or 80s or who receive “compassionate” releases because of failing health, Bolus is just 48 and could lead a long life outside prison—but only if the governor lets him.

“I don’t think someone can fake 25 years of caring for other human beings. I don’t think a person can fake 25 years of educating myself,” he said. “I don’t think people serving these types of sentences come out of prison wearing a mask. … This is who they are.”

Staying positive despite the overwhelming odds against his eventual release can be difficult, Bolus acknowledges, but he credits his deep religious faith, as well as the connections he has made with other prisoners, as a source of hope that he will one day be free.

“There’s so many people cheering me on,” Bolus said. “I can feel that something’s changing.”

This story is part of a series that The Appeal is co-publishing with Gothamist, a nonprofit news outlet focusing on New York City.