Why Are Women Getting Stuck in Rikers?

New York City has reduced its jail population, but those who remain are staying longer.

In 2013, Tatyana Gudin was arrested for drug possession with intent to sell, a charge she denies. A year later, she missed a court date and was remanded to Rikers Island.

Initially held in a 50-person dorm in the women’s facility, known as the Rose M. Singer Center or Rosie’s, she was temporarily moved to an enclosed individual cell. She said she was never given a reason for the transfer, but it gravely affected her mental health. Gudin said she suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder and anxiety.

“I cannot be locked in,” she told The Appeal. “I was freaking out.”

Gudin, like many women, entered Rikers already suffering from past trauma and mental health issues. A higher percentage of women than men in the city’s jail system grapple with these burdens, and that makes women harder to serve—and harder to decarcerate.

Over the last three decades, New York City has decreased its jail population from a high of nearly 22,000 in 1991 to just above 8,000 today, giving it the lowest jail incarceration rate among all major U.S. cities. Just 13 percent of people arrested in New York today are taken into Department of Correction custody. A 2017 plan released by Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration for closing Rikers by 2027 calls for the city to decrease its jail population to fewer than 5,000 people over the next decade.

But advocates say women are often left out of that conversation. “The relative obscurity of women in the overall system has resulted in far fewer, if any, reforms targeted towards this population, despite growing momentum for criminal justice reform,” the Vera Institute of Justice and the New York Women’s Foundation noted in a new report on women in Rikers.

Of the roughly 500 women now in city jails, many have significant unmet needs such as homelessness and substance use disorder. On average, women have fewer financial resources, which can result in an inability to pay bail. And because most jailed women are mothers, their incarceration can have sweeping consequences for families.

Increasingly, activists are putting pressure on the city to pay more attention to women in the criminal justice system. Members of Close Rosie’s, a group that includes formerly incarcerated women, say the factors that lead women to jail, not to mention the issues they face once they’re there, mean most of the women shouldn’t be incarcerated in the first place. Their group is calling for the women’s jail on Rikers to be closed first.

“It has to be phased out,” said Close Rosie’s co-founder Kathy Morse. “But let’s make Rosie’s the priority.”

Barriers to decarceration

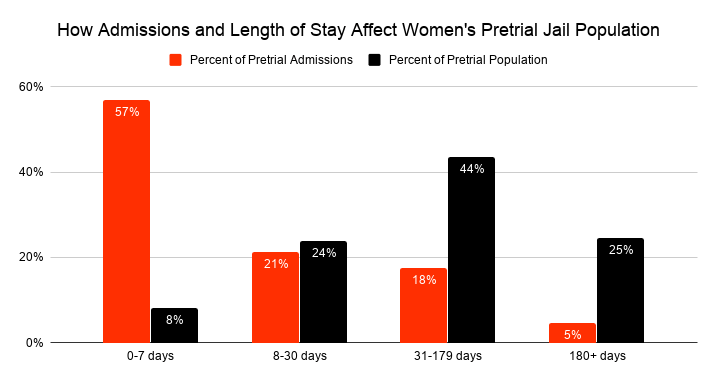

Two key numbers determine the size of a city’s jail population: admissions and average length of stay. The more people admitted to jail custody, the more people there are behind bars. But equally important is how long they stay.

In New York City, just 6 percent of people admitted to jail will stay longer than six months, but they account for nearly half of the jail population on any given day. In contrast, more than half of all people admitted to jail will be bailed out in less than a week, but those defendants account for just 2 percent of the population.

Reducing jail populations requires tackling both of these numbers. For instance, if the city stopped jailing everyone with bail set at $2,000 or less, it would cut admissions by more than half, but reduce the daily population by just 3 percent, according to a recent report by the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice. In fact, the same report notes, most people detained pretrial in New York City today couldn’t be released on bail, even if they could afford it, because of existing warrants or holds from other cases.

The women’s jail population in New York City is a mix of short-stayers and long-stayers. A 2017 report by the Prisoner Reentry Institute found that 60 percent of women admitted to jail in the city were released within two weeks.

On any given day, however, most women in custody have been there ten weeks or longer. Those women are more likely than the short-stayers to be dealing with such issues as untreated mental illness or substance use, and they often have warrants or holds that make them ineligible for release on bail. People with mental health diagnoses stay in DOC custody nearly three times as long as those with no diagnosis, and the disparity is even greater among women.

Even a short stay in jail makes a woman more likely to face longer stays in the future. “Women are coming back in because they have a parole hold or they had a turnstile jump or a shoplifting case, or something like that … and didn’t come to court,” said Insha Rahman, an author of the Vera report. “When they come in on this new felony larceny case or a felony drug case, they’re definitely going into jail because you had this other warrant that you just ignored.”

Research shows women tend toward different crimes than men, often ones driven by instability and poverty. Women are far less likely than men to be arrested for crimes like robbery or gun possession. Instead, they typically face arrest on charges such as larceny, which doesn’t involve the use of force, or drug possession, both of which stem from poverty and behavioral issues.

“Property offenses and drug offenses are sort of the typical female crime. Either shoplifting or in some cases … stealing things out of people’s cars,” said Meda Chesney-Lind, a criminologist at the University of Hawaii and an expert on women’s incarceration. “And it’s usually for economic reasons. So it’s poverty-driven.”

Even violent crimes by women are different from those committed by men. Research shows that the majority of violence by women is connected to interpersonal relationships. Sixty-two percent of violent crimes by women involve someone they know, compared with 36 percent of violent crimes by men.

Property offenses and drug offenses are sort of the typical female crime. … And it’s usually for economic reasons. So it’s poverty-driven.

Meda Chesney-Lind University of Hawaii

Jailing women, even briefly, can have devastating ripple effects, advocates note, because roughly 80 percent of incarcerated women are mothers.

“Two weeks is nothing when you think about a public-safety benefit,” said Rahman. But two weeks can unravel a woman’s life, she explained. “If you have a job, you will lose it. You had housing, you will lose that. If you have your children in your care, you will lose that. If you don’t have your children in your care and you’re trying … to get them back in your care, you will lose all the opportunities to do that, too.”

‘A terrible place to do time’

Local jails such as Rikers play an outsize role in women’s incarceration. A report released last month by the Prison Policy Initiative found that nearly half of all incarcerated women in the United States are held in local jails, compared with less than a quarter of men.

This poses a problem for women dealing with chronic mental health or substance use, because jails are less equipped to provide long-term care and rehabilitation.

“Jails are set up to be temporary places,” said Aleks Kajstura, the legal director at the Prison Policy Initiative. “The long-term programs aren’t in place in the way that prisons are, because even though prisons fail at it, there’s supposed to be this corrective theory behind it. Not that they do a good job of it, but they are at least programs that are trying to give people some skills.”

Chesney-Lind agreed. “Jail’s a terrible place to do time,” she told The Appeal, “especially if [women] have mental health issues, they shouldn’t be in jail. They should be getting help to deal with those issues.”

In an email, the Department of Correction noted that it runs a wellness initiative, as part of New York City first lady Chirlane McCray’s Women in Rikers initiative, and offers intimate partner violence counseling and discharge planning. Most DOC facilities have a mental health clinician on duty, and mandatory training courses help correction officers recognize signs of distress in inmates with mental illness.

Approximately three-quarters of women in DOC custody have mental health diagnoses, according to Department of Correction data. That’s far higher than in the jail population overall, where 43 percent of people have mental health diagnoses.

Some of the incarcerated women wrestle with both mental illness and drug use. And Rikers is home to the oldest and largest jail-based opioid treatment program in the United States, which served nearly 4,000 patients in fiscal year 2018.

It’s just this constant thing of women being put in the back seat or women being ignored.

Kathy Morse Close Rosie’s

“They may be self-medicating. They’re using the drugs maybe because of their trauma histories. They may have PTSD, depression,” Chesney-Lind told The Appeal. “And they need help. They need help dealing with what originally caused the trauma. That’s likely a major factor in their drug use.”

According to an Idaho State University survey, 86 percent of women in jail nationwide have experienced sexual violence and 77 percent have experienced partner violence.

“For [incarcerated] women, it’s pretty staggering. It’s nearly universal that they have histories of trauma and abuse,” Elizabeth Swavola, a senior program associate at the Vera Institute, told The Appeal.

Swavola noted that day-to-day practices in a jail can be retriggering for women with histories of trauma. Correction officers and prison staff are “often not trained in trauma and understanding trauma and how it impacts the mind and the body, and how women respond when they’re triggered. So oftentimes their responses are interpreted as being disobedient, but it’s really that they are responding to trauma,” Swavola said.

But even “standard practices can be really triggering for women who’ve experienced trauma,” Swavola said. “So things like shackling, or being put in solitary confinement, being observed [when using the restroom or changing clothes].”

The push to close Rosie’s

Women often face additional trauma while incarcerated. There are at least three open lawsuits alleging sexual abuse in the jail and at least two lawsuits alleging rape that were recently settled. In August, the Legal Aid Society filed a lawsuit against the city on behalf of Jane Doe, who accuses two Department of Correction officers of raping and sexually abusing her when she was incarcerated in 2015. One of the correction officers, who has since been fired, pleaded guilty to a felony rape charge.

“The vast majority of our officers carry out their duties with care and integrity, and we are taking many steps to ensure that all staff adhere to the highest professionalism,” the department’s press secretary, Jason Kersten, said in a statement at the time.

Close Rosie’s started after organizers became frustrated with what they saw as a lax attitude in the Department of Correction toward sexual assault and harassment. Members of the group said women were barely mentioned when city officials talked about reforming the criminal justice system or closing Rikers Island.

What do we do with these cases where it’s not as simple as $500 bail as the barrier between this person and their liberty?

Insha Rahman Vera Institute of Justice

Over the last year, activists with the group have spoken out at Board of Correction hearings on the department’s compliance (or lack thereof) with the federal Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA).

On Sept. 6, the city council held a hearing on sexual assault and harassment at Rikers. During the hearing, the Department of Correction admitted there were hundreds of sexual assault complaints from 2016 that had still not been investigated two years later.

“It’s just this constant thing of women being put in the back seat or women being ignored,” said Morse.

The Department of Correction told The Appeal that it has hired 26 additional sexual assault investigators and expects to clear the complaint backlog by February 2019. The department says it has trained more than 7,000 staff on PREA and is working with Safe Horizon, a nonprofit, to provide a confidential crisis hotline in jails.

In a statement, the Department of Correction’s Kersten said, “The safety and wellbeing of those in our custody is our number one priority. As we continue to make strides in reducing the jail population, we’re also working around the clock to deliver services to some of our most vulnerable populations: from increasing hard and soft skills vocational training to incorporating programming that is responsive to those with mental health challenges, young people and women.”

The broader solution, advocates say, is to work on keeping women out of jail in the first place.

“You’re basically spending money jailing people who are marginalized either economically or in terms of their physical challenges,” Chesney-Lind said. Later, she added: “If you just let everybody, let all the women out, that’s a good place to begin in terms of weaning ourselves off of mass incarceration.”

The advocacy group Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights spent more than $1 million in October on a bailout focused on freeing women and young people from Rikers. According to the New York Times, it succeeded in releasing 105 people, 62 of whom were women.

Rahman praised the bailout for focusing on providing support for women after release too, noting that further decarceration will require the city to go beyond traditional measures such as bail reform or reducing low-level prosecutions. Rahman said the city should invest in expanding comprehensive approaches, such as supportive housing enriched with services for people released from custody. The city contracts with nonprofits to run a transitional program, for instance, for homeless women leaving jail.

“What do we do with these cases where it’s not as simple as $500 bail as the barrier between this person and their liberty?” asked Rahman. “For the most part that’s not what we’re contending with when we talk about further decarceration in New York City.”