Instagram Photos Offer Glimpse Inside Notorious Georgia Jail

The DeKalb County Jail, now at the center of protests, has a long history of problems and a legacy of housing people for unpaid fines.

It started with a photo on social media. During a video visitation last month at the DeKalb County Jail in Decatur, Georgia, people detained at the jail tried to show some of its conditions to their loved ones.

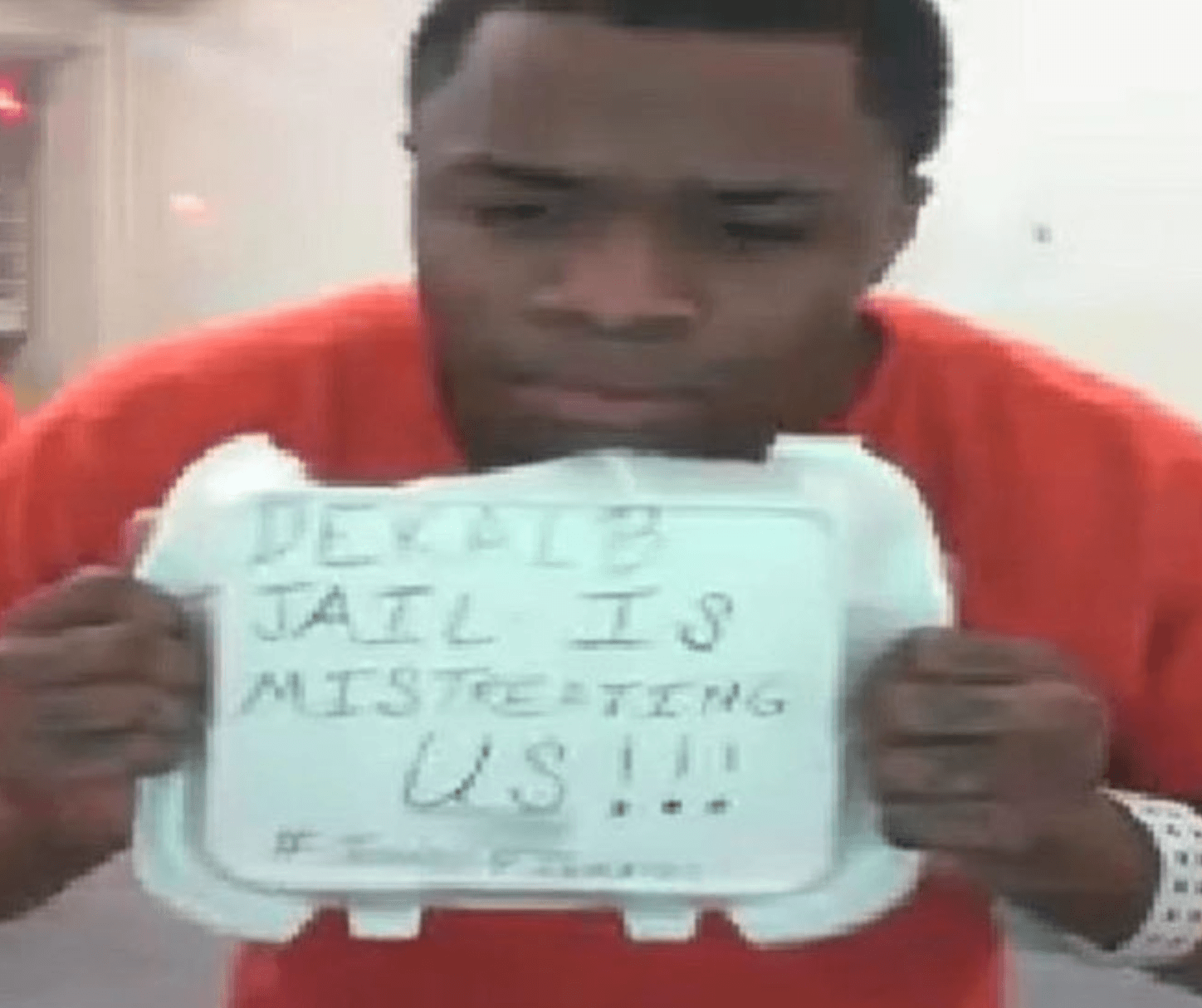

Malaya Abdullah-Tucker, who said her son is in the jail, took screenshots and posted them on Instagram. In one photo, a detainee holds up a sign that reads “DeKalb Jail is mistreating us!” Another shows what appears to be a meal served at the jail. A third shows a man holding up a sign that says “We sleep and breathe mold.”

“STAND FOR THESE YOUNG MEN!” Abdullah-Tucker wrote in her caption. “They are caged away with no voice! No matter what they are incarcerated for, they do not deserve to live in such treacherous conditions!”

The Instagram photos have helped spark recent protests, including one last Wednesday during which four protesters were arrested.

Yet some of the issues the prisoners raised have dogged the jail for more than a year. According to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, DeKalb County Sheriff Jeffrey Mann has requested more funding over the past two years to address mold and other issues at the jail. Last year, he announced a $1.5 million effort to address mold and improve plumbing at the facility.

Mann disputed the protesters’ allegations that the jail is unsanitary and said they should call with complaints instead. “[They’re] just out there creating a disruption rather than being productive and rather than calling, emailing, or going on the website,” he told reporters. “It’s not fruitful.”

But critics say their concerns about the jail go beyond its conditions. It has long been known as a so-called debtors’ prison because of the county’s willingness to jail people for unpaid fines and fees. In January 2015, the ACLU sued DeKalb County on behalf of Kevin Thompson, a teenager who was arrested for not being able to pay $838 in fines and fees related to a traffic violation. According to the suit, he was not offered counsel or an indigency hearing.

“Across the county, the freedom of too many people is resting on their ability to pay,” Nusrat Choudhury, an ACLU attorney who represents Thompson, said in a statement at the time. “We seek to dismantle that two-tiered system of justice, which disproportionately punishes people of color.”

When the plaintiffs and defendants settled the lawsuit two months later, DeKalb County agreed to have its judges use a “bench card” that reminds them of the legal alternatives to jail and the procedure to figure out if a defendant is able to pay a fine. In reforms that followed the settlement, the county granted residents six weeks to pay off fines, and the option of working them off with community service (at $8/hour).

But according to the ACLU of Georgia, some of the problems persist. At the time of the lawsuit, traffic violations were usually handled in the DeKalb County Recorders Court, where the county charged a $25 court fee on top of the fine for each traffic citation. The Recorders Court was ultimately shut down and replaced with the traffic division of DeKalb County State Court, but that court reinstated the fee.

People who can’t pay court fees or traffic citations right away are often put on probation for as long as a year, until they can pay them off, according to the ACLU of Georgia. When the cases are handled by municipal courts rather than state court, defendants are more likely be jailed for nonpayment, ACLU staff attorney Kosha Tucker told The Appeal. Often, defendants appear in court without a public defender to help them negotiate a better outcome, she added.

“The absence of counsel, coupled with the monetary consequences of a misdemeanor conviction, raise serious concerns about the creation of debtors’ prisons and the criminalization of poverty in municipal courts,” Tucker wrote in an email.

Last year, the Institute of Justice filed a lawsuit against the DeKalb County town Doraville, alleging that its ticketing practices (handled through its municipal court) that generate revenue for the town are unconstitutional.

The town’s mayor and city manager could not be reached for comment by press time. District Attorney Sherry Boston declined to comment on her county’s use of jail time for overdue fines and fees and referred questions to the solicitor-general’s office, which declined to comment. The DeKalb County Probation office did not respond to a request for comment.

DeKalb County Jail has also been accused of medical neglect. Over the last decade, the jail had the second-highest number of jail deaths in the state, according to an analysis by the Journal-Constitution. In 2015, Ricky Figueroa died by suicide after repeatedly asking for mental health treatment, including filing four grievances with that request. Shantell Johnson was admitted to the jail in 2013 for driving with a suspended license and was found dead in her cell less than 48 hours later. Although an internal investigation found no violation of policy in the leadup to her death, her family is now suing the sheriff’s office.

The office of Sheriff Mann, who took office in 2014, did not return calls or emails seeking comment on the deaths.

Meg Dudukovich of the Atlanta Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee, which is helping to organize the protests at the jail, told The Appeal she sees the deaths as part of pattern of neglect, both by the jail and the public. “I think that America dehumanizes prisoners so much that a lot of people just assume, ‘Oh, if they’re in jail then they deserve these conditions,’” she said.

“DeKalb has had these issues for decades,” Dudukovich added. “It’s been a well-known secret for a long time.”