We Can’t Let Our Children Go Hungry

Since the pandemic began, vital programs that enable children to receive free meals, such as the National School Lunch Program, haven’t been reaching the families in need of support.

This commentary is part of The Appeal’s collection of opinion and analysis.

As roughly half of elementary and high school students across the country have (necessarily) started the year remotely, people are asking whether students will be able to learn through a computer screen. This concern is justified, but it has also overshadowed a far more fundamental question: whether students will be able to eat.

America’s children are in grave danger of malnutrition and starvation right now. That’s because, for many children, the meals provided through the National School Lunch Program are the only ones they get. But since the pandemic began, these vital programs haven’t been reaching families in need. In fact, a researcher at the Brookings Institution found that only about 15 percent of low income households who qualify for free or reduced-price school meals are actually receiving them.

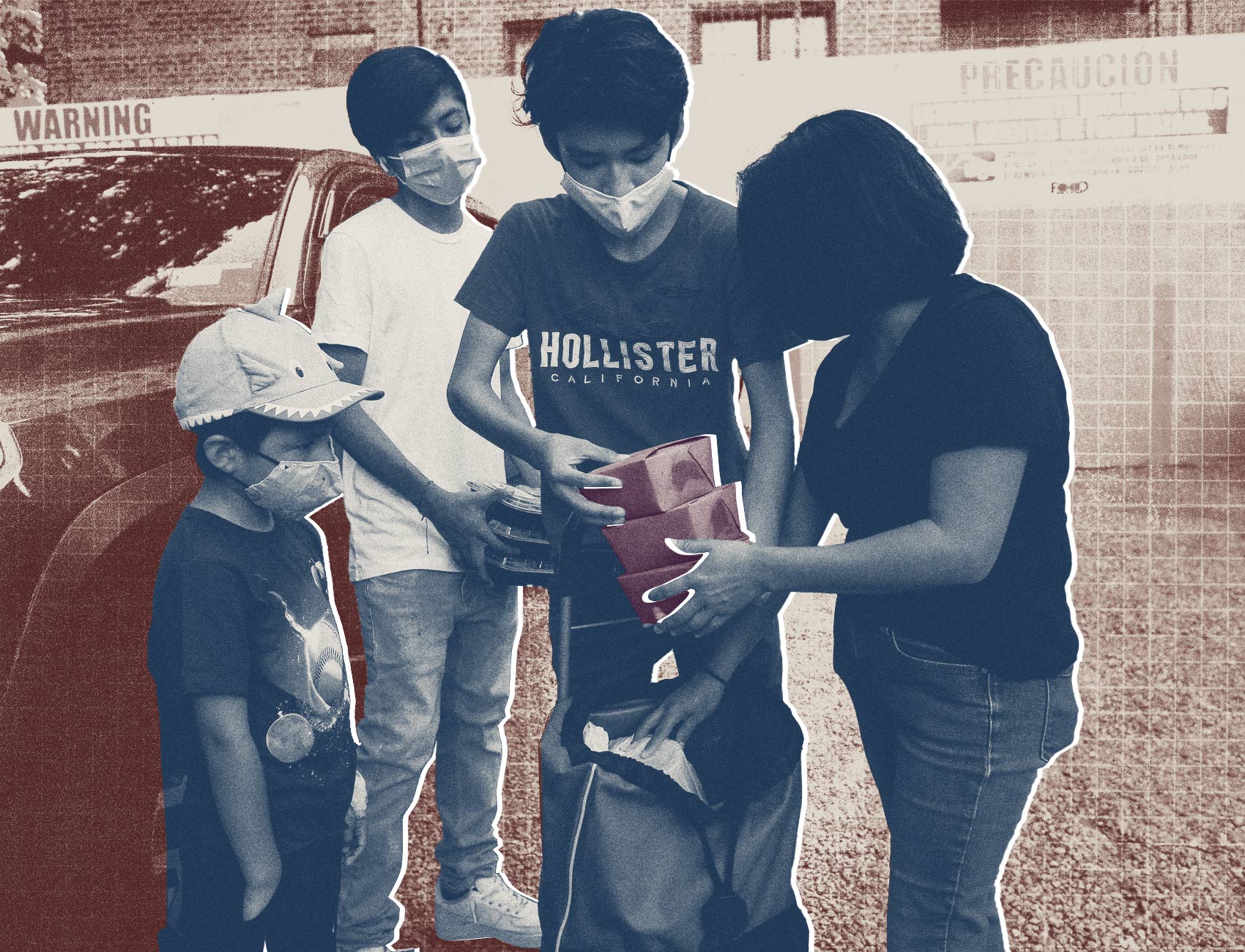

While many school districts and volunteers have done heroic work to try and get meals to students, in most areas free school meals still have to be picked up in person—and many parents simply can’t get away from work or caregiving, don’t have access to transportation, or may be too health-compromised to risk leaving the house every day.

The current crisis in the Bronx is being ignored or—worse—covered up by the Department of Education. Principals are facing thousands of families who have not connected with schools or city agencies, and they desperately need help and support. Principals have a unique vantage point of poverty; I know this because I was in their place less than a year ago.

This crisis obviously impacts all children from neglected communities, but it is even more pronounced for the 114,000 New York City public school students who are homeless—a population that has been overlooked for decades. In my 20 years as a public school educator and principal in NYC, I saw this neglect firsthand.

The bottom line is that for many homeless families in New York City, the uncertainty surrounding when public schools would return to in-person instruction, five days a week, has translated to chronic uncertainty about how they will feed their children.

Unfortunately, hunger is not the only challenge that our children are facing. Many children have watched loved ones become infected by the coronavirus and have lost family members. They are coping with the mental health toll of social isolation. And many families are falling deeper into poverty as parents lose their jobs and are at risk of losing their homes.

Schools have historically been a safe haven for our kids, and it has never been more essential that we make sure they can still be, even during this pandemic. Our children desperately need stability and safety right now. We must work to protect both the physical and mental wellbeing of all of our students.

In addition to ensuring that our schools are a resource and support system for vulnerable students and families, we should be reaching the families that need help most. Schools already have relationships with the city’s most vulnerable children. We need to leverage these relationships and listen to what school administrators are learning from them, so we can better deliver social services and meet the needs of all families.

We need to reimagine interagency collaboration to holistically address the needs of our children. In New York City, it is time for the Department of Education, the Department of Health, and the Department of Homeless Services to work hand in glove. We need an accurate accounting of what’s happening in the homes of our children, and we need to allocate resources accordingly and set up an efficient system to meet their diverse needs—beginning with hunger.

We can start by extending the Pandemic Electronic Benefit Transfer (P-EBT). It’s a federal food-stamp initiative that provides funds to families that did not receive school meals because of the pandemic—or at least it did until it was allowed to expire on September 30. But merely extending this program will not be enough; we must do more for our students to ensure that all their needs are met.

We need more creativity in how we solve our societal problems. In this case, we should implement a food delivery system that works for and individually addresses the needs of all families. Parents could fill out virtual “Blue Cards” and work with schools to identify food-related needs. The schools could then communicate these needs to the Department of Health, which would work with local distribution centers to ensure that food is delivered to hungry students. By creating a system of collaboration between families, schools, and government agencies, we can make sure all of our children receive three meals a day, including on weekends. Right now, none of this is being done.

The federal government has the infrastructure in place to support and feed our kids. During this tumultuous time, these structures should be fully funded. Systems should be in place to provide our kids with the food, technological, and mental health support they need. If the federal government fails to step up, child hunger, domestic violence, community violence, and already existing learning gaps will skyrocket.

Since the very start of this pandemic, our federal government has ignored our most basic needs. From failing to protect our health from this deadly virus to refusing to even consider the HEROES Act in the Republican-led Senate, the American people—and especially the country’s most vulnerable children—have been left out to dry.

We have repeatedly failed to protect our children from the pain and suffering the pandemic has inflicted. But my hope is that an issue as simple and universal as child hunger can unite us and spur the federal government into action.

We can’t let our children go hungry.

Jamaal Bowman is a former middle school principal and the Democratic nominee for New York’s 16th congressional district.