Political Report

“How Are You Keeping My Community Safe If You’re Stealing My Resources?”

A candidate for prosecutor in Loudoun County, Virginia responds to attacks on her background and argues that criminal justice reform can help public safety.

A candidate for prosecutor in Loudoun County, Virginia responds to attacks on her background and argues that criminal justice reform can help public safety.

It’s a well-worn campaign trope: Criminal defense lawyers facing attacks based on the people they represented in court.

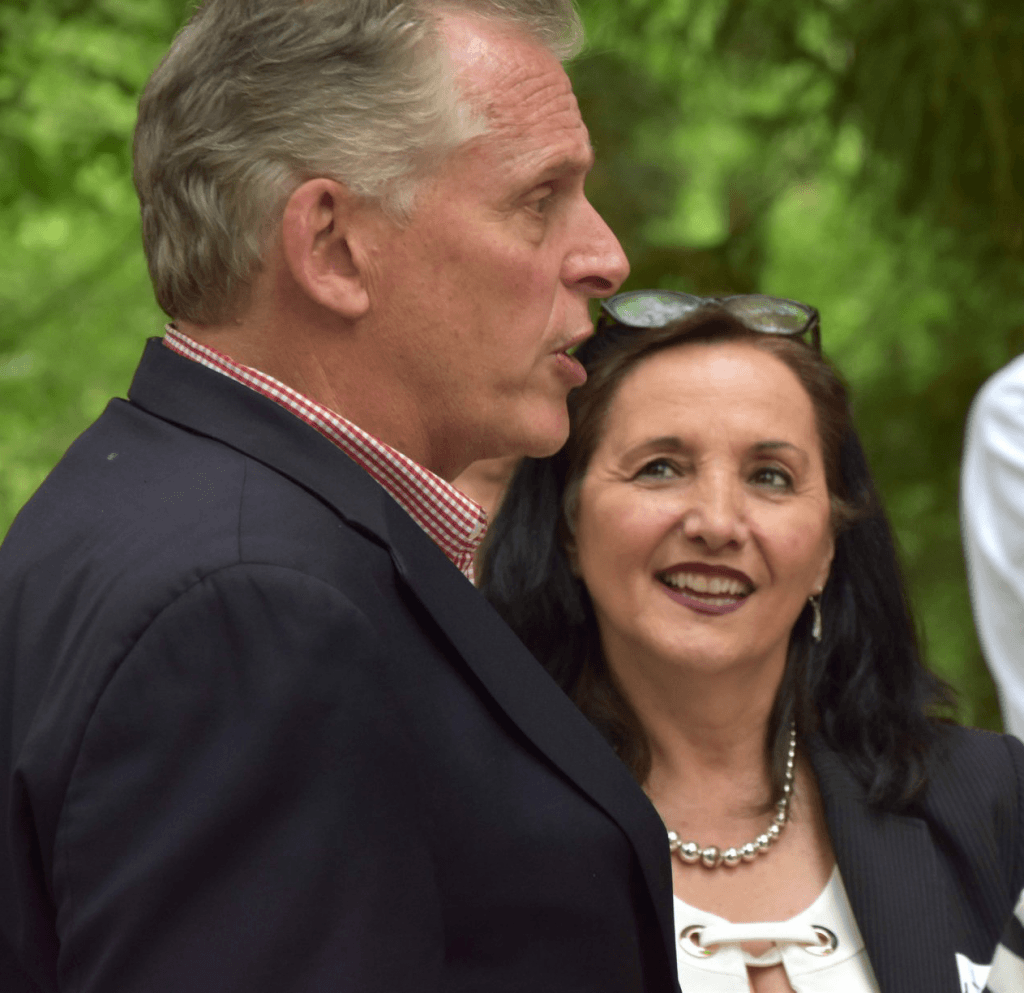

The latest to face such rhetoric is Buta Biberaj, who is now running on a reform platform as the Democratic nominee to be the next commonwealth’s attorney of Loudoun County, Virginia, a populous jurisdiction in the Washington, D.C., suburbs.

“My opponent makes her living by defending criminals and suing the police,” Nicole Wittmann, Biberaj’s Republican opponent in the Nov. 5 election, wrote on Facebook last week, an apparent reference to criminal defense work that Biberaj has done. Wittmann wrote elsewhere that Biberaj has “made a career out of attacking victims” and “coddling criminals.” She has also raised fears about public safety, stating, again on Facebook, that “Biberaj is #unsafeforLoudoun.” Wittmann, who is the county’s chief deputy prosecutor, did not answer requests for comment on these statements regarding Biberaj’s career or views, nor on her own views regarding prosecutorial practices.

Biberaj talked to the Appeal: Political Report on Saturday about her professional work. “I made a living defending the accused in criminal cases,” Biberaj said. “The Constitution affords anyone a basic right to counsel … There’s nothing more basic or more pure than somebody who represents somebody who’s accused by the government of having done something.”

Biberaj repeatedly described why she thinks the status quo is what harms public safety, and why reforming the criminal legal system is important to improving it.

Asked about Boston District Attorney Rachael Rollins’s argument that it is a “myth” that public safety stems from aggressive “broken windows”-style policing toward all illicit behavior, Biberaj faulted the harsh prosecution of lower-level offenses as a misallocation of resources. “How are you keeping my community safe if you’re stealing my resources and funneling them to those low levels, but you’re not able to prosecute the most significant crime?” she said.

Saddling people with criminal convictions for lower-level offenses “doesn’t make our community safe,” she argued. It “flattens” their chances of success and sparks a cycle encounters with the criminal legal system, even if they receive a probation term rather than incarceration.

To reduce the volume of convictions, Biberaj said she favors new pretrial diversion programs for people charged with lower-level charges (including marijuana possession, theft of under $500, disorderly conduct) to “earn” a dismissal of their case. However, she also said she would not adopt a policy of declining to prosecute marijuana possession, as Stephanie Morales has done as prosecutor in Portsmouth and as other Northern Virginia candidates are proposing. A diversion policy would still require her office to expend some resources on monitoring those cases.

She has also staked less far-reaching positions than we have seen elsewhere on other issues. She said she would back restoration of voting rights upon completion of a person’s sentence, rather than at earlier stages, and in another interview, she would not commit to never seeking the death penalty.

In her interview with the Political Report, Biberaj also made the case that public safety calls for protecting victims and defendants alike, and that this means ensuring a fair pretrial process. “You don’t protect victims by victimizing others,” she said. She committed to not call on testimony or reports by police officers with a documented history of misconduct, and also to electronically share information with the defense counsel throughout a case. “We shouldn’t be using the power of information and failure to provide as a means to convict somebody,” she said.

She argued in a similar vein that prosecutors should not be involved in immigration enforcement because that would make the office “look that much more forceful in trying to bully or take advantage of somebody’s status by threatening them with that.”

Finally, Biberaj said she would have the commonwealth’s attorney office begin collecting and release racial and demographic data for charging and sentencing decisions. She cast this as a necessary step to address racial disparities, and patterns involving law enforcement “overpolicing on one side” while “not doing the same investigation into others.”

The winner will replace Commonwealth’s Attorney Jim Plowman, a Republican set to become a judge next month. County politics shifted during Plowman’s 16-year tenure, from a double-digit win for President George W. Bush in 2004 to a double-digit win by Hillary Clinton in 2016.

The interview has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

Your opponent, Nicole Wittmann, wrote in a Facebook post, “My opponent makes her living by defending criminals,” which may be a reference to work you have done as a criminal defense attorney. I believe this can be a jumping-off point for us to discuss the prosecutor’s role, but first: What is your reaction to the suggestion that it is untoward, and I quote again, to “make a living by defending criminals?”

I’m going to change a word: I made a living defending the accused in criminal cases. If you look at the U.S. Constitution, there is the Sixth Amendment, which has a right to counsel. I’m upholding the Constitution. And if she doesn’t respect that, then she should never be a lawyer, and she definitely should not be a prosecutor because you’re missing the point that the position of a prosecutor is to seek justice, not to seek convictions only. The Constitution affords anyone a basic right to counsel, any time that they’re accused of something that might cause them to lose their freedom. There’s nothing more basic or more pure than somebody who represents somebody who’s accused by the government of having done something.

Her choosing the word criminal is intended to inflame the community and to make it sound like those people are bad people. What it doesn’t do, it doesn’t take into account those many cases that you say people have done something wrong, and they have not done something wrong, or they’ve done something less wrong than what they’ve been accused of. That’s what criminal defense attorneys do: They keep the system honest, from government and prosecutors overreaching.

Do you think your defense experience is relevant to the work of a prosecutor, and if so how?

Of course. Let’s talk about the breadth of the experience. As a defense attorney, what do you do? You take the case that the prosecutor has, how they have charged somebody, and you’re trying to figure out whether or not the government has the elements that they need to prosecute; you are assessing the value of their case. Additionally, you’re trying to see where the law is in your client’s favor, so that you can establish that what they’re accused of they did not do. You also, because you’re doing trial work, are charged with knowing the rules of evidence, and making sure that the rules are followed so that if the government is trying to put in evidence that is not admissible or appropriate, you have the knowledge that they don’t get that evidence admitted. I am also a civil attorney: I prosecute cases from the civil aspect. So you have the same types of procedures, other than the areas of law. You’re looking at civil law, but you are still prosecuting. So when she tries to narrow that down and say I’ve never been a prosecutor, that’s disingenuous because I have been a prosecutor in civil cases for the last 25 years.

One area where Virginia prosecutors face criticism for disrespecting the rights of defendants is discovery rules: The state Supreme Court delayed its mandate that prosecutors reform their policies, so prosecutors retain significant discretion. If elected, would you commit to a practice of easily sharing the evidence and documents pertaining to a case with the defense in a quick manner, and what would be the parameters of this?

You have to provide the information to the accused in a timely fashion. If I’m the prosecutor and at the beginning of a case and I have the evidence, my obligation is to provide that evidence to them on the front side of the case, and as I learn more to give it to them. People cheat with open file discovery. If you come on day three, and look at my file, I show you whatever I’m wanting to show you. But then I may add something on day 25 or day 30, and if I don’t let you know, then I cheat you by saying, well, we had open-file discovery. Why didn’t you come back every day? Well, you can’t expect somebody to do that. That’s just cheating. So my policy in my office is going to be this: We’re going to provide discovery and more importantly, we’re going to create a system where we put it on a disk for you, so that you know exactly what you got, you know exactly what you saw, and you know exactly what we gave you.

So there’s none of that hiding and cheating and lying, because that creates mistrust in the system. We want to create trust in the system, so that if somebody is truly guilty, then they’re going to be found guilty. If they’re not guilty, then we shouldn’t be using the power of information and failure to provide as a means to convict somebody because we think that they should be found guilty. That just makes everybody unsafe when they’re dealing with the system.

One implication in some of your opponent’s statements about you is that there’s a dichotomy between the rights of the victims and those of defendants. Do you share a characterization that these two sets of rights are at odds with one another? And if not, what’s your method or perspective to avoid pitting them against one another?

If you look at the purpose and function of a prosecutor, it’s to do justice. That means you have to protect the victim, and you protect the accused, and you protect the system. So they’re not an either/or. You have a duty to all of them. No victim wants to get up one morning and say, “Oh my God, he’s the person who was convicted in my case for 10 years in prison, and now I have to find out that they weren’t a guilty person.” You didn’t protect anybody; you actually put the community at odds with their safety because the bad guy is out in the community. That’s why you have to hold the system to such a high standard, and prosecutors to such a high standard. So no, there is no either/or. If you create a system where people believe that they’ve been treated fairly, you can protect the interests of all of them. You don’t protect victims by victimizing others. You protect victims by doing justice because then the right thing happened in those cases, and victims feel secure that their voices are going to be heard, their interests are going to be protected, and the community is protected. That’s all that we want.

You just said that, with this sort of opposition, people “put the community at odds with safety.” I would like to know more about how you understand safety and its relationship to criminal justice reform. Rachel Rollins, the Boston DA, wrote in an op-ed titled “The Public Safety Myth” that, “We have been told that our communities are safer with each criminal that our local law enforcement locks up—often for low-level offenses like drug possession, shoplifting, or loitering. The problem with this narrative is that it’s largely false, predicated on a pervasive and pernicious myth known as ‘broken windows’ theory.” I understand you may not have read the essay, and so I am not asking you to comment on it overall. But what do you think of the specific claim I just read that, that law enforcement has often been predicated on the false broken-windows premise, which ends up prosecuting any illegal behavior too harshly, and that this harms safety instead of helping it?

I am going to answer this first question: How do I even interpret the word safety? Safety is literally—one—me being safe physically in my community, my property being safe. But safety is also this: the knowledge and trust in the system. If I am a victim, I have to trust the system and have to feel safe that if I pick up the phone and I call law enforcement, they’re going to come and ask me what happened, and that they’re going to properly investigate, and based on what they find that they’re going to bring it to the prosecutor. The prosecutor is going to do the job with integrity, and charge the person who had committed the offense, and charge them appropriately, so that when that person comes to court, that person also can trust that they’re not being overly prosecuted, or treated differently because of their race, their religion, their socioeconomic status, or their educational status. So whoever comes before the court can feel safe that they’re going to have a fair day. That’s safety for the community. Then we know that where our resources are being used, is the best use.

When we go out there and prosecute people for these low-offense crimes—I’ll tell you, I specifically had this case: A 19-year-old boy got stopped at a traffic stop. Officer asked him “Do you have anything in the car?” He said, “no.” “If I search your whole car, I’m not going to find anything?” The kid says, “Well, you might have some crumbs on my floorboard.” The deputy scrapes that up, charges my kid with 0.001 ounce of marijuana. Do you know how small that is? When you take resources and you suck them down like that, that’s not helping my community because then those resources aren’t available to prosecute more significant crimes, which are sex crimes, violent crimes, sophisticated crimes, where you really have to find the time to do it. How are you keeping my community safe if you’re stealing my resources and funneling them to those low levels, but you’re not able to prosecute the most significant crime?

Now, let’s assume those crumbs really are marijuana and he gets found guilty. You’ve labeled this 19-year-old boy as a drug addict or drug criminal. Who’s going to hire him? What happens to his life successes? It’s flattened. How are you helping my community when he, at the age of 19, doesn’t get the opportunity to be more successful? Why can’t we take those types of cases and do a number of things? One is do we even take a 0.001 ounce? Do we even prosecute it? And if we prosecute it, do we give this kid an opportunity to do community service or do something to say, “You know what, you’re right, I messed up, but give me an opportunity to make better decisions in the future and be more successful”? The more successful he is, the more successful we are as a community.

He also doesn’t come in and out of the system because what ends up happening is when you put people for low-level offenses into the system, almost 99 percent of the time it’s attached to some sort of probation. On probation, I am all over you, and I don’t know what type of person you are, and I have no reason to believe you are anything other than a good person. But if I watch you for 24 hours a day, seven days a week within one week, you probably committed reckless driving if you were driving. You may have thrown a piece of paper on the floor. In Virginia, that’s a misdemeanor. You may have said the F-word once. That could be another curse and abuse. You may poke somebody or nudge somebody. That’s an assault. With those little minor things, I’m going to end up violating you on your probation. I’m going to put you back into the system, and put you back into the system, and put you back into the system. So you get that recidivism. So when we talk about safety: That doesn’t make our community safe. You make our community unsafe because now you’re creating this line of criminals, because you’re going to be able to never let them get out of that. So when somebody yells safety and it’s about those things, that’s a red herring.

So in such lower-level cases, what would you do that’s not being done? Other candidates or prosecutors have proposed policies of just not taking on certain types of offenses, specifically marijuana. Is that a kind of policy you would like to pursue? If not, what else would you be able to do to avoid devoting resources on low-level offenses?

Right now in Virginia, marijuana is illegal. So it’s not a matter that you would completely not prosecute those cases. What we would do is we would direct them towards a diversion program so that individuals who are charged with such an offense have the opportunity to not have a conviction. That would be literally across the board on that. I have expectations that in Virginia, within the next couple of years, it’s actually going to be decriminalized. So Virginia is starting to move in that direction where they understand that that’s not the best use of resources. What you do is you create opportunities where individuals, through community service and other aspects of their disposition, can earn a deferral or a dismissal so they’re not hampered by those convictions.

So this would be a pre-conviction program that you are proposing? And if so, are there other types of low-level offenses where you would like preconviction diversion programs?

Here in Loudoun County, we started the drug court. That has been for individuals who’ve been in and out of the system for a while; it requires them to have an opportunity to be able to stay out a prison. But this is the hang-up on that one: One, it requires them to plead guilty. Second, they have to concede, before they step in the drug court, that if they violate they will receive an 18-month prison sentence. That’s not something that is, in my eyes, appropriate because you don’t even know what their violation would be. How can you concede and say 18 months is appropriate? What you’re doing is you’re asking somebody to give up their right to be able to successfully argue to the court that they should have a different sentence, just so they could get the benefit of participating in the drug court. That’s not a treatment-centered proposal.

Are there charges other than marijuana where you would implement an approach of systematically trying to avoid a criminal conviction through alternative programs?

Yes, theft for values under $500. Then you also have things such as trespassing and disorderly conduct. We would also have the option for any first offense—that is fact-specific—but not one where there’s been a violent injury; that would also be something that would be for fair consideration.

You said earlier that you would want people who call your office to feel safe to do so and come forward. One place where people voice concern is immigration enforcement, and fears that if you are undocumented, it may be a problem to engage in law enforcement or the prosecutor’s office. What would you want to do as prosecutor so there are no immigration consequences for people who engage your office, whether as plaintiffs, victims, or defendants?

Within the prosecutor’s office, if they are a complaining witness or victim, that is at the discretion of the office as to whether or not they notify anybody. I would expect and I would hope that the office would not be reporting anyone if they are a victim, or a witness in a case. But the fear is what’s stopping people from coming in or participating in the process. How you change that is by affording them the opportunity to have those conversations and educating them through community contacts.

As for the accused, the prosecutor’s office should not be involved in that because it has a tendency to make that office look that much more forceful in trying to bully or take advantage of somebody’s status by threatening them with that, so what do they do? Do they enter a guilty plea? Do they do something else that otherwise they wouldn’t do because now that you know that I’m not documented, you’re going to go ahead and report me, so therefore I have to do something that I am less inclined to do?

Returning again to what safety means: Overpolicing and overprosecution poses safety issues of their own to people of color, and African Americans in particular. How should you as prosecutor confront racial disparities in how people experience the criminal legal system?

We need to establish a process by which we can gather data. Because right now, we don’t have the statistics in Loudoun. We can talk anecdotally, but if your experience is not my experience, you’re going to say, well, that’s not really what happens. With you looking at data or at cases, you can have a conversation with law enforcement as to why we have a greater percentage of this group versus another group, and what type of offenses. Is it overpolicing? Is it a matter that special groups get certain privileges, that they don’t get charged, and that they might get a warning? When we look at the racial disparity, there are certain presumptions and expectations and attitudes that law enforcement may take with one race group that they don’t with another. If they stop a person that is white, they may not ask or they may not create an opportunity to search the car. That doesn’t mean that that person hasn’t done anything wrong, but if I’ve been searching every car of a minority, it’s kind of self-fulfilling that, “Oh my gosh, those are the people who are committing these crimes.” No, it’s because you’re not doing the same investigation into others and you’re overpolicing on one side.

So you would commit to collecting and releasing racial and demographic information having to do with charging and sentencing decisions in the office?

Oh, yes. That’s the first thing that we would so, create an alliance with an institution that is doing that so we can incorporate that in our office. Otherwise you can’t make changes because you don’t know how you’re affecting the community.

There have been calls around the country for prosecutors to not call on police officers who have a documented pattern of misconduct, or racial misconduct, or lying. Is that something you would set up in Loudoun County, a process to not rely on law enforcement officers with a problematic history on these issues?

Let me answer that a little more fully than you asked it: My opponent has also accused me of going after police officers, and she’s 100 percent right. I sue police officers who violate the Constitution or who violate my clients’ rights because they make my community unsafe. And as a prosecutor, you’re right: If somebody comes before me and they are known to be lying in a case, you will never come before my court again, and I will not prosecute a case that you have. That would be a conversation that we would have with that person; it’d be a conversation that we have with either the chief of police or the sheriff’s office. They should not be on the police force. That police officer makes it dangerous for other police officers. That police officer makes it dangerous for our community because they lose trust in it. And this is what we don’t want. There’s no police officer that I’ve ever spoken who said, “Yes, I like having bad police officers on the force and I think we should keep it that way.” That is a community investment if we free up those people who are not doing their job right and who are making our community unsafe.

What are two or three reforms that you wish passed at the statewide level on the set of issues that affect your office or criminal justice?

One should be the automatic restoration of someone’s voting rights. This should be something the system should reinstate automatically after the requisite period of time, where they’re off probation, off parole, they’ve served their time.

Second one is expungements. And that also should be something where if somebody has had their charges nol-prossed or dismissed because they are found not guilty, that those also should be automatically expunged by the system. That should not be a process that they have to undertake. Related to that, there should be a law that websites that have information regarding someone’s charges, that when somebody gets an expungement that they should be obligated upon notice to take the information off their website.

The third one is there has to be a greater information as far as victims’ rights, as to what they can do to get services within the community that are more global. It shouldn’t just be while in the case and while the trial is pending; it also should be beyond that, as to where I can go to be able to obtain services at a reduced cost or free, so that I can actually engage in the healing process. While I’m in the middle of a trial, that’s a time of crisis; somebody’s not ready to really receive and benefit from services. It’s after the trauma of the case that they can do that, and we don’t do a good job in providing those services.

On your first point: Do you favor automatic restoration of rights after the completion of a sentence, or are open to earlier stages of a sentence, as we’ve seen in some states this year that have restored voting rights to people on probation or parole?

After the completion of their sentence.

A lot of what we’ve talked about has been about the criminal legal system, and a prosecutor’s role there. A prosecutor can also influence community programs or services beyond the criminal legal system. You have spoken about what happens in schools, for instance. What should a prosecutor’s role be to diminish the reliance on the criminal legal system, and to expand community investments or social services that aren’t reliant on the criminal legal system, that can diminish the need for the prosecutor to be involved in the first place?

Not only have I been a civil attorney and a criminal attorney for 25 years, but I was also a guardian ad litem. That is an attorney that the judges appoint for elderly and children, to protect their best interests. We always worked toward trying to find services for somebody. Also, having been a substitute judge for almost 12 years, we have people assigned or directed to go to different programs. But as you said, it’s always been through the criminal justice system. What we need to do, and what my platform in part is, is trying to create the synergy of different partners. We need employers to be able to come and be part of the system so when somebody is out of jail and they’ve served their time, that they can find a job. We need our mental health services and our private partners within the mental health community to see what they can do to provide services, both while somebody is in the middle of a crisis or in the midst of incarceration, and then beyond, so when they come out they have those services —working with the schools. We also have to look at the board of supervisors to make sure we have funding, and where we get funding is by redirecting our resources: If we’re spending in Loudoun County $66,000 a year to incarcerate somebody, we take that $66,000 and instead invest it somewhere else. That’s money freed up for us to be able to do more services. Those are the things that we want to be able to do, for that weight to be shared by the entirety of the community because it benefits the community. How does the prosecutor do that? By being engaged in a community. Our prosecutors are not engaged in the community. They don’t go out and try to create these partnerships. They are literally just focused on checking the box, prosecuting, convicting, and then incarcerating. That’s their whole focus because then they think that they’ve served their purpose. But they have to be much more modern-thinking as to what safety and justice really mean for our community.