Victims’ Families Want Virginia to End The Death Penalty

Virginia may soon become the 23rd state to abolish capital punishment.

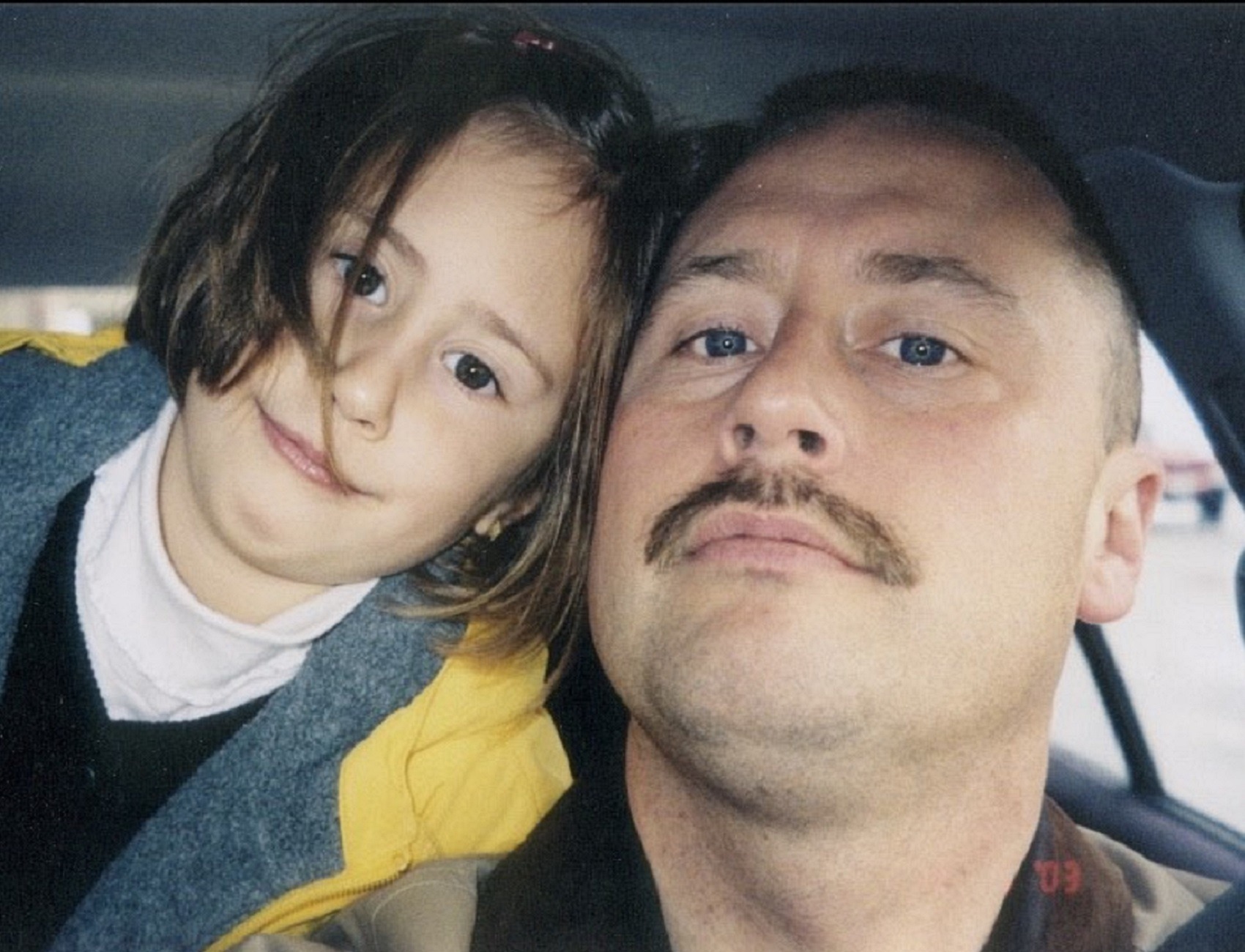

Before William Morva was executed in 2017, Rachel Sutphin wrote to Virginia’s then-governor Terry McAuliffe asking him to spare Morva’s life. When Sutphin was nine-years-old, Morva shot and killed her father, sheriff’s deputy Eric Sutphin.

Sutphin is now a 23-year-old seminary student working to end the death penalty in Virginia. This week, about 20 family members of murder victims, including Sutphin, released an open letter to members of the Virginia General Assembly, calling on lawmakers to abolish capital punishment and replace it with life in prison without the possibility of parole. Among the signatories are three state legislators who all lost loved ones to murder.

“I remember feeling that it brought me no solace,” Sutphin told The Appeal of Morva’s execution, which she did not attend. “Now my family’s grieving and his family is grieving, but it brings no justice, no fulfillment. It just causes more trauma and more pain.”

Virginia—once one of the country’s most frequent executioners—is potentially weeks, if not days, away from ending capital punishment, with legislators expected to vote on a bill that would ban the practice. Two amendments were introduced this week, including an amendment that would retain the death penalty for people convicted of the capital murder of a law-enforcement officer and people convicted of capital murder for the killing of more than one person as part of the same act. Legislators are expected to debate the amendments next week.

Prior to the introduction of the amendments, Governor Ralph Northam said he supports the legislation. If Virginia bans the death penalty, it will be the 23rd state to abolish capital punishment in the United States and the first to do so this year.

Morva was the last person executed in Virginia, on July 6, 2017.

In addition to Sutphin, others tried to stop Morva’s execution—state legislators, the European Union, the U.N. special rapporteur for arbitrary executions, and the U.N. special rapporteur for mental health. At the time of the crime, Morva, who was severely mentally ill, was suffering from delusions, according to his lawyers. When he was not incarcerated, he ate raw meat and pine cones, believing he suffered from an intestinal disorder.

But McAuliffe was not persuaded. “I personally oppose the death penalty,” he said in a statement, announcing his decision to decline Morva’s clemency petition. “However, I took an oath to uphold the laws of this Commonwealth regardless of my personal views.”

McAuliffe never responded to Sutphin personally, she told The Appeal. He recently announced he’s running to be governor a second time, and that he supports a ban on capital punishment.

“I was raised—my father being a police officer—that you can trust the government, that the government’s there to protect you, but they didn’t answer me,” she said. “I do appreciate that Governor McAuliffe has now said that if he is governor again he will support the abolishment of the death penalty, it feels almost too late for me.”

Morva’s execution did not bring closure, said Sutphin. “Now there’s two dates that I remember every year,” she said. “I remember Morva’s execution and my father’s death … For me, true closure would be abolishing the death penalty.”

A diverse coalition has emerged in support of ending capital punishment in Virginia. Earlier this month, a dozen chief prosecutors in Virginia sent a letter to legislative leaders calling for, among other reforms, abolishing the death penalty. “The death penalty is unjust, racially biased, and ineffective at deterring crime,” the prosecutors wrote. “It is past time for Virginia to end this antiquated practice.”

In recent years, the death penalty has been all but non-existent in Virginia. A death sentence has not been handed down in Virginia since 2011, and there are only two people on its death row. If the amendment that retains the death penalty is passed, both people on death row would still be eligible for execution. Despite its infrequent use, its abolition is still necessary, say advocates. A de facto moratorium does not indefinitely protect the lives of those on death row. Until last summer a federal execution had not occurred in 17 years. And then between July and January of this year, the federal government executed 13 people.

“Virginia has executed more people than any jurisdiction in the United States since the founding of Jamestown and the first execution in 1608,” said Michael Stone, executive director of Virginians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty. “If we can turn the page on capital punishment I think that sends a strong message that the time of the death penalty is coming to an end.”