Newsletter

Without Political Change, Police Brutality Footage Has Become Trauma Porn

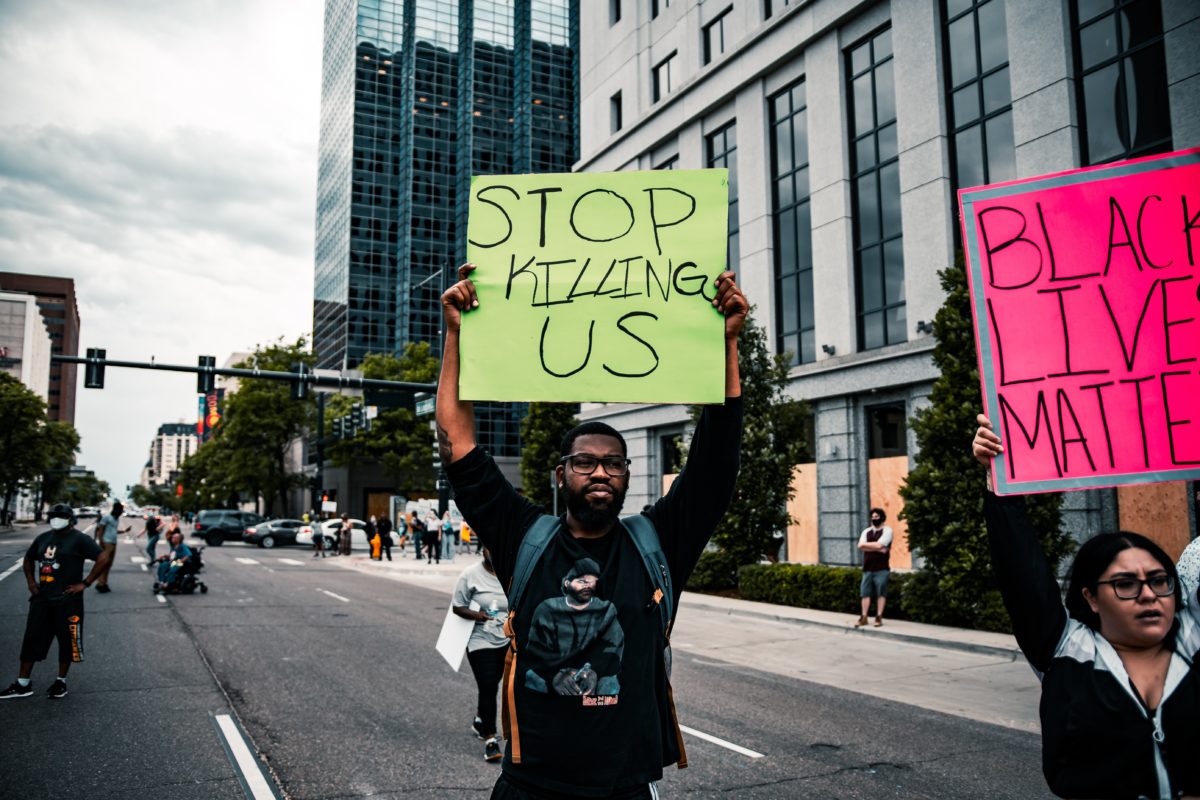

Absent structural organizing and actual political change, societal consumption of anti-Black violence instead reinforces the dehumanization of Black people that is central to white supremacy.

Without Political Change, Police Brutality Footage Has Become Trauma Porn

by Nneka Ewulonu

American law enforcement, with its roots in slave patrols, has historically been a tool used by the white and majoritarian society to oppress marginalized communities—especially Black people. In recent years, many of those who believe that we can fight this violent history by regulating and training police departments have pitched video surveillance technology, such as body cameras, as a potential way to hold officers accountable and prevent brutality from occurring.

But that violence has not stopped, and footage of anti-Black violence at the hands of law enforcement now floods news channels and social media feeds regularly. Most notably as of late, the Memphis Police Department released a video of its officers savagely beating 29-year-old Tyré Nichols to death at the end of January.

As Nichols’ murder and its aftermath have shown, the public continuously consumes this media under the misguided belief that simply bringing awareness to police brutality and anti-Black racism will stop these horrors from occurring. In reality, the mass consumption of Black trauma and death is itself another example of white supremacy’s stranglehold on American society. While body-worn cameras and cellphone footage may seem like new inventions, the public has been “raising awareness” about police violence for the majority of the last century. History shows us that no amount of media consumption will diminish the amount of violence, often at the hands of the state, that Black Americans experience.

In contemporary America, the fact that police officers disproportionately target, harass, and kill Black people is known to all except those who chose not to see it. More grotesque depictions of anti-Black violence will not change the state of affairs on their own. Absent structural organizing and actual political change, societal consumption of anti-Black violence instead reinforces the dehumanization of Black people that is central to white supremacy.

Trauma porn—defined by Black Public Media as “media stories depicting the inhumane and often exploitative treatment of BIPOC individuals by police and/or White civilians”—perpetuates Black people’s victimhood, rather than diminishing it. Violence should not occur in silence; outlets do have a journalistic duty to inform the public of instances where those in power abuse the marginalized. But detailed, thorough reporting is a far cry from directly watching the torture, abuse, or murder of a Black person captured on video.

Anti-Blackness as a spectacle is nothing new. White people have long intentionally and joyfully consumed Black misery. Lynchings were common in 19th and 20th century America and were explicitly public occurrences—even family entertainment, with parents and children attending and bringing food and drink. Local newspapers would detail the murders, including graphic photos of the victims. Perpetrators and onlookers often took souvenirs from the victims. Prominent white lynchers were lauded by local newspapers and posed with their children near the deceased for photos.

One of the most well-known civilian attacks on a Black person in American history began on August 20, 1955, when 14-year-old Emmett Till, a Black boy, was accused of flirting with a white woman while visiting family in Mississippi. Four days later, the woman’s husband and his brother brutally beat, shot, and dismembered Till, then threw his body into a river.

His mother, Mamie Till Mobley, rejected a mortician’s offer to “touch up” Till’s body. Instead, she chose to have an open casket funeral exposing her son’s grotesquely mangled form to illuminate the horrors of Jim Crow segregation and anti-Black racism in America. An estimated 50,000 people saw Till’s body during his funeral in Chicago. The national magazine Jet subsequently published photos of his corpse.

While Till’s death was at the hands of civilians rather than police, Till’s killers felt empowered to murder the boy because of state-sanctioned segregation and anti-Blackness. But simply publicizing images of Till’s body was not enough to spark meaningful societal change on its own—it took nearly a decade of concerted, direct political organizing to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964. To this day, despite Till’s story and photos being taught in school, memorials for Till are routinely defaced and vandalized. The gruesomeness of his murder is mirrored by the callousness with which society objectified Till’s corpse and memory.

Civilian footage started proliferating almost 40 years later. On March 3, 1991, a bystander named George Holliday filmed from his apartment balcony with a home video camera while a Black man named Rodney King was beaten by police during his arrest. Officer Lawrence Powell swung his baton, hitting King in the head and causing him to fall to the ground. Officers Powell and Timothy Wind continued to viciously beat King. Holliday sold the video to a local TV station, which then sold it to CNN. The video became international news and provided explicit, recorded evidence of anti-Black police brutality. The public wondered once again whether this footage would be enough to change law enforcement permanently. But in the decades since, the cycle has only repeated itself. Footage of police officers killing Eric Garner and George Floyd within the last decade sparked international protests but little, if any, structural changes to law enforcement.

Earlier this year, on January 7, 2023, Nichols was pulled over by Memphis police during a traffic stop. Officers dragged Nichols from his car, attempted to tase him, and then chased him on foot. When the police reached Nichols, five officers pummeled him in the head and body. The officers left Nichols on the ground for 20 minutes before emergency responders began treating him. He died three days later. Shortly before the Memphis Police Department released the footage, Police Chief Cerelyn Davis said the officers showed a “disregard of basic human rights.” But in the weeks since, the department has done next to nothing to structurally change the way it polices Memphis, aside from abolishing the small strike-force-style unit that killed Nichols. While that one team in one locality may be gone, many similar units still exist around the country.

These incidents, spanning more than 70 years, each feature the public supposedly coming face to face with the horrors of anti-Black violence. In theory, the visualization of violence against Black people should force viewers to reckon with racism, spurring awareness and change. But these examples instead make clear that no amount of visual reckoning with trauma porn can create change on its own. The nation must dispose of the idea that “activism” means simply sharing videos of police brutality online, as opposed to actual involvement in political organizing or community aid.

The consistent portrayal of anti-Black violence not only solidifies Black people as victims in the minds of white Americans, but also exposes Black Americans to repeated depictions of their own dehumanization. In 2016, clinical psychologist Monnica Williams told PBS that police brutality videos can trigger PTSD-like symptoms in Black Americans. In 2018, a Harvard University-led study found that, when police kill an unarmed Black person, it negatively impacts the mental health of nearby Black residents for months afterward. Combined with the fact that this footage has so far done little, if anything, to change American policing, trauma porn is ineffective at best and immoral at worst.

The only thing that will stop anti-Black violence is rooting out the anti-Blackness present throughout American culture. In the words of abolitionist Angela Y. Davis, “in a racist society, it is not enough to be non-racist, we must be anti-racist.” We must intentionally uplift Black experiences and address Black people’s needs. There is no need to subject ourselves to the assault or murder of Black Americans in the interim.

In the news

A Republican lawmaker in Tennessee was forced to apologize after he suggested bringing back “hanging by tree”—i.e. lynching—as a state-sanctioned method of execution. A measure to approve executions by firing squad is still under consideration. [Craig Shoup & Kirsten Fiscus / Nashville Tennessean]

It is the responsibility of journalists to “resist industry-typical copaganda and instead produce reporting that focuses on transformative and reparative practices and informs readers how to keep their communities whole, safe, and accountable,” Tina Vazquez writes in an editorial. [Tina Vazquez / Prism]

Police in South Carolina arrested and charged a woman last month for allegedly taking abortion pills to end her pregnancy. The incident took place in October 2021, before the fall of Roe, but South Carolina is among the few states that ban self-managed abortion. [Susan Rinkunas / Jezebel]

Progressives and advocates for D.C. statehood are fuming after Biden announced he would sign into a law a GOP-led effort in Congress that could override changes to the city’s criminal code, recently passed by the city council. In a statement, Biden claimed he supported “home rule” for D.C., even as he supported efforts to overrule changes “such as lowering penalties for carjackings.” [Kyle Feldscher, Maegan Vazquez & Manu Raju / CNN] MORE: Critics of D.C.’s crime bill are misleading the public about its actual effect on penalties for offenses like carjacking. [Mark Joseph Stern / Slate]

“The pen became my sword and a way to stand up for myself and the many around me who didn’t have a voice loud enough to reach to the outside world.” Christopher Blackwell, a contributing editor to The Appeal, talks about how he got interested in writing and journalism while in prison. [Famous Writing Routines]

ICYMI — from The Appeal

Why are New York courts and the Manhattan DA fighting an HIV activist’s efforts to get removed from the sex offender registry over a nearly 15-year-old conviction in Louisiana for “illegal HIV exposure”? Adam Rhodes has the latest on the legal battle.

In 2015, Los Angeles County created a new department to help divert people with mental health needs out of jail. But since then, the number of people with mental illness incarcerated in the county jail system has only gone up, Meg O’Connor reports.

Nearly 200 New Orleans police officers were accused of sexual misconduct, intimate partner violence, or harassment from 2014-2020, Meg O’Connor reports. The NOPD investigated itself and sustained only 3 percent of complaints involving sexual or intimate partner violence.

That’s all for this week. As always, feel free to leave us some feedback, and if you want to invest in the future of The Appeal, donate here.