‘They Sent Him to His Cell to Die’

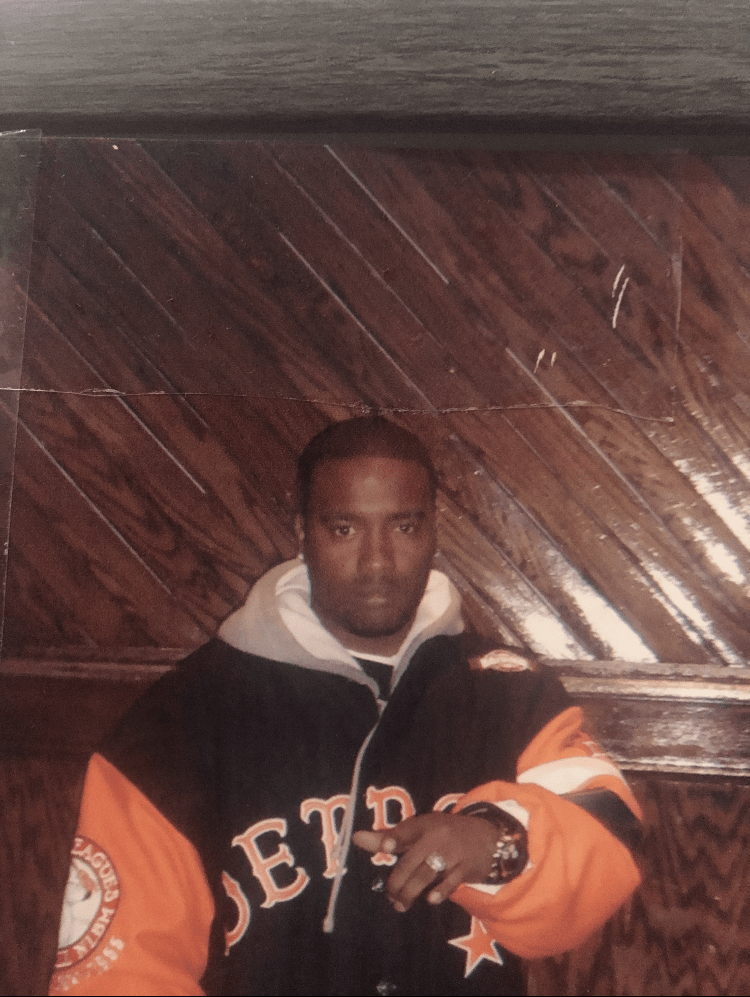

Rashad McNulty entered a guilty plea in a series of federal gang indictments in New York that have been criticized as racist and overly punitive. But before McNulty was even sentenced, he died in jail. Now, his family is seeking justice.

It was just after 2 a.m. on Jan. 29, 2013, and Rashad McNulty sat in the clinic of the Westchester County Jail in Valhalla, New York. The 36-year-old initially described the pain as centralized around his abdomen, but then insisted to jail nurses he had never felt pain like that.

McNulty was diagnosed with indigestion and was given Mylanta and Zantac, over the counter drugs commonly used to treat heartburn and upset stomach. At around 4 a.m., McNulty told jail staff he was feeling better and was taken back to his cell. But less than 30 minutes later, McNulty collapsed in the hallway of his cell block and appeared to be unresponsive. “I don’t want to die,” he said.

Jail nurse Paullete Smith told McNulty she would take him back to the infirmary. But according to a Westchester County Department of Correction report, Smith changed her mind when McNulty suddenly got up on his own and slumped into a wheelchair.

“I’ve been doing this too long to be fooled,” Smith allegedly remarked to another jail staff member. She took McNulty’s blood pressure and wheeled him back to his cell and left. According to a statement from a corrections officer who periodically checked on McNulty that morning, his moans of discomfort were so loud that they awoke people housed on his cell block who then waved down a corrections officer.

At approximately 5 a.m., McNulty was unresponsive. Smith returned to the cell block, observed McNulty and yelled for a corrections officer to call 911. Around five minutes later, Smith administered CPR to McNulty, but he was still unresponsive. At 5:45 a.m., paramedics arrived at McNulty’s cell and he was then taken to a nearby hospital. But McNulty’s condition did not improve: He was pronounced dead at 6:16 a.m.

“He did everything he was supposed to do,” Jared Rice, an attorney representing McNulty’s fiancee in a federal civil rights lawsuit against the Westchester County Jail and its medical services provider, told The Appeal. The lawsuit claims the jail provided “grossly negligent” medical treatment to McNulty and had “deficient policies, practices and customs related to the provision of healthcare services. “He asked for help multiple times. He was patient, he was polite, and they just ignored him and they sent him to his cell to die. It was a death sentence.”

Gang raids gain steam

An April 25 report from the Bureau of Justice Statistics estimates that in mid-2017 (the most recent year for which statistics were available) county and city jails held approximately 745,000 people, about two-thirds (482,000) of whom were unconvicted and awaiting court action. Approximately 263,000 people housed in city or county jails were convicted and serving a sentence or awaiting sentencing. Rashad McNulty was one such person. He was awaiting sentencing in a federal case, set for two weeks after his January 2013 death.

On Aug. 9, 2011, McNulty was among 62 people arrested in an early morning, mutl-agency raid in Yonkers involving the FBI, Drug Enforcement Administration, New York State Police, and the Westchester County district attorney’s office. Hundreds of agents and officers carried out raids across more than a dozen locations and seized cash, firearms, crack cocaine and marijuana. Preet Bharara, then the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York, announced the indictment of those arrested on narcotics and firearms charges and claimed that 59 of the defendants were members or associates of two street gangs, the Elm Street Wolves or the Cliff Street Gangsters.

Bharara said the takedown was the largest joint federal and local law enforcement action in recent memory in Yonkers. “It means that everyone should be on notice that if you join a gang, or deal drugs or engage in violence in Yonkers, you are facing federal time now,” he said. The Elm Street Wolves indictment was part of a much larger gang policing strategy by New York law enforcement that culminated in an April 2016 raid of the Eastchester Gardens projects and other homes in the Bronx.

Known as the “Bronx 120,” it was the largest gang raid in New York City history and involved federal, state, and local agencies. But advocates, families, and criminologists alike say the basis for gang policing—“the full force and power of the department, and its partners, would surgically remove individuals who were allegedly terrorizing city neighborhoods,” as The Appeal recently reported—masked a dragnet approach that criminalized wide swaths of people in poor, majority-Black neighborhoods. “What we’re finding is that many of these conspiracy indictments are overly broad, that they sweep up young people [who] have no connection to violence and not even any allegation of a connection to violence,” Alex Vitale, a sociology professor at Brooklyn College in New York and the author of “The End of Policing,” told The Appeal. “They mislabel the deep social networks that exist in many of these communities as evidence of gang connectedness.”

In 2016, then-NYPD Commissioner William Bratton described alleged gang members as the main driver of violence in New York City. But according to a new study of the Bronx 120 case by City University of New York School of Law professor Babe Howell, nearly 60 percent of defendants pleaded guilty to selling marijuana or other drug-related offenses. Just 4 percent pleaded guilty to murder. On April 26, WNYC host Brian Lehrer referenced Howell’s study and asked New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio if gang indictments are “criminalizing communities based on who they know.” De Blasio said he hadn’t read the study but insisted there was a “high bar” to bring gang prosecutions and that the cases “resulted in making a lot of communities safer.”

In the Elm Street Wolves case that ensnared McNulty, federal prosecutors alleged that the gang’s leader Stephen Knowles ordered beatings, engaged in shootouts, and committed armed robberies to defend a sprawling and illicit Yonkers-based drug enterprise. But McNulty’s alleged involvement in the drug business was far more limited. Prosecutors said McNulty sold crack cocaine near Elm Street on or about July 7, 2011, approximately one month before he was swept up in the raid. And McNulty was among 47 people charged with selling crack cocaine, 41 of whom were also charged with firearm possession in relation to the much larger conspiracy alleged by prosecutors. “When you’re charged federally and they put all these resources into arresting several individuals and tying them all together, even if you’re only charged with selling one crack rock, your exposure to time is so significant that most often individuals plea bargain for the lowest amount of time they could get because they don’t want to get lumped into the more serious charges of other individuals who they were arrested with,” Rice, McNulty’s attorney, said.

On Sept. 5, 2012, McNulty entered a guilty plea to conspiracy to distribute 28 grams of crack cocaine and a firearms charge. The father of six was engaged to be married and faced at least five years in federal prison. But McNulty did not even make it to sentencing in federal court. On Nov. 27, 2013, Bharara filed a motion to dismiss the charges against McNulty because “while awaiting sentencing, McNulty died.” Bharara attached a copy of McNulty’s death certificate to the motion, which was signed by a federal judge on Dec. 9, 2013.

Bharara did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Lawsuits suggest inadequate medical care

A 2015 investigation of McNulty’s death by the New York State Commission of Correction found that his symptoms were “highly indicative of acute coronary syndrome.” The commission also determined that Smith and another jail nurse committed professional misconduct when they failed to take McNulty’s medical care seriously, improperly documented his condition and abandoned him when he was in obvious distress. “Had McNulty been given appropriate emergency medical care and sent to a hospital in a timely manner, his death may have been prevented,” wrote correction commissioner Dr. Phyllis Harrison-Ross in an 8-page, partially redacted report.

The commission suggested that the state medical licensing office investigate Smith for professional misconduct. She left Correct Care Solutions, the jail’s medical services provider, shortly after McNulty died, the Journal News reported in 2015.

On March 15, a federal judge in New York denied a motion by Westchester County and Correct Care Solutions, the county jail’s medical service provider, for a summary judgment in the McNulty family’s civil rights lawsuit, which would have required the judge to decide the case instead of a jury. The family lawsuit noted that the Department of Justice determined in 2009 that the Westchester County jail did not provide adequate medical care and that Correct Care Solutions was named as a defendant in more than 140 federal lawsuits alleging inadequate healthcare. Neither Westchester County nor Correct Care Solutions LLC—which in late 2018 was acquired by Wellpath, a company providing medical and behavioral healthcare services to patients in inpatient and residential treatment facilities, civil commitment centers, and local, state and federal correctional facilities—responded to The Appeal’s requests for comment.

A father missed, his story untold

Rice told The Appeal that he is seeking a seven-figure amount in damages for McNulty’s children. When McNulty died in 2013, he was the father of two 18-year-old girls, a 14-year-old son and two younger daughters, ages 8 and 7. He also had a 6-year-old son.

“His children are getting older now,” Rice said. One of McNulty’s youngest daughters who lived with him when he was arrested is now old enough to read online accounts of what happened to her father. She has been asking questions about his arrest in the gang raid and about his death in the jail, Rice said.

Had McNulty received proper medical care in the Westchester jail and made it to his sentencing, Rice added, he would be able to tell his own story.

“I believe he’d be home today,” he said.