‘There’s An All-out Manhunt’: A Strike Organizer Speaks From Prison

An imprisoned organizer with Jailhouse Lawyers Speak said prison officials are trying to identify those leading the strike.

Since the nationwide prison strike began on Aug. 21, prison officials have retaliated against those involved, monitoring correspondence and putting some prisoners accused of organizing in solitary confinement. It has been hard for those on the outside to get information about what’s going on.

The Appeal recently spoke with an incarcerated man in South Carolina who helped organize the strike. He said officials in his prison have made it clear they want to root out and punish those behind the action.

“Right now, we know there’s an all-out manhunt for Jailhouse Lawyers Speak leaders,” Eddie (not his real name), a member of Jailhouse Lawyers Speak (JLS), which organizes for prisoners’ rights, said in a call with The Appeal and other journalists. “They want to take our heads off. We’re not going to give them our heads. We’re not gonna let them destroy our movement. It’s not going to happen.”

The South Carolina Department of Corrections (SCDC) said there was no strike in its prisons, and disputed the notion that it was looking for organizers. “We have not seen any evidence of the prison strike,” said Dexter Lee, interim communications director for the department.

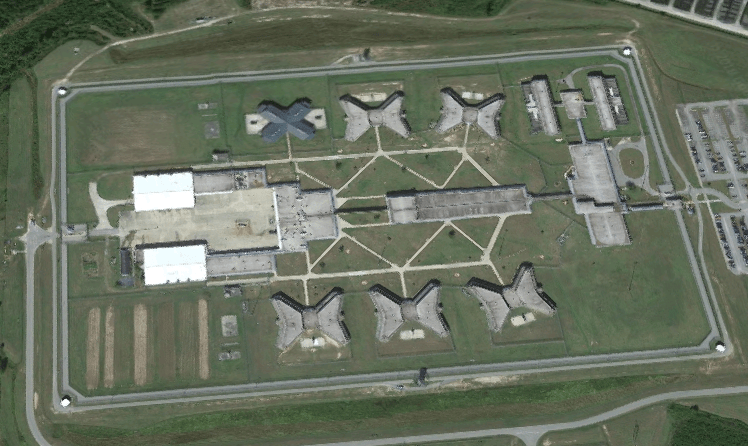

In April, Jailhouse Lawyers Speak called for a national prison strike from Aug. 21 until Sept. 9, an action sparked by a riot at Lee Correctional Institution in South Carolina that left seven prisoners dead and injured at least 22 others. “The seven didn’t just die, they bled out,” Eddie said, a fact confirmed by the Lee County coroner. “We want everyone to remember the horrific conditions that brought these deaths about.”

Since the beginning of the strike, the Industrial Workers of the World’s Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee has reported strike activity in at least 10 states. In Ohio, two prisoners have reported that they are on hunger strike. In Indiana, prisoners in a solitary confinement unit initiated a hunger strike to protest inadequate food. In North Carolina, prisoners hung banners from their recreation yard.

Like many prison housing units in South Carolina, Eddie has been on lockdown since the riot in April. Eddie said prisoners in most units at his prison have been locked in their cells for 24 hours a day, only coming out to shower twice a week, with no outside recreation or sunlight. “We have steel plates over the windows so there’s definitely [been] no sunlight coming into the rooms [since April],” he said.

Jailhouse Lawyers Speak members communicate to prisoners nationwide through publications, newsletters, and unauthorized cell phones, and with the help of their supporters. This was how prisoners learned about the national strike, and also how JLS knows which prisons have participated. To halt the strike, Eddie said, prison officials are trying to interrupt these communications. In South Carolina after the riot, prison officials began testing cell-phone blocking technology.

“I think that some of these prisons have been very effective with some of these measures they’ve been taking out as it relates to our communications,” Eddie said. “I’ve seen a drastic increase in confiscation of cell phones and stopping publication[s]. The way we usually communicate.”

Dexter Lee of the South Carolina Department of Corrections did not respond to a question by press time regarding the confiscation of cell phones. He said that 8 out of 21 facilities under SCDC’s control have “various housing units” on lockdown “for the safety of staff and inmates.” Regarding how many hours per day prisoners were kept in their cells, he said, “The exact amount time during a 24 hour period will vary depending on services such as mail, visitation, telephone calls, showers, medical care or other services.” He acknowledged that there were plates over the windows in some units “to combat contraband.”

The prison strike call-to-action outlined four activities prisoners could participate in—work stoppages, hunger strikes, boycotts, and sit-ins—to open the opportunity to all prisoners, not just the ones who work. Eddie said JLS members at his prison have been focusing on boycotting the commissary.

He said he hopes the strike will “raise awareness among the prisoners as to what the issues really are. What are the conditions that are shaping and fomenting the violence amongst us back here? And what are some of the issues we really need to be coming together on to address as a collective?”

Eddie places the blame for the state of America’s prisons on lawmakers at the state and federal level. “What’s happening inside these prisons, lawmakers created it. … They created these conditions,” he said. “If we keep on this same track, we’re going to have issues far worse than they’ve ever seen, far worse than Attica.” The strike is timed to end on Sept. 9, the same date as the Attica rebellion in 1971.

Jailhouse Lawyers Speak members have decided to remain anonymous in their interactions with the public to try to prevent the type of retaliation launched against leaders of the 2010 work strike across six prisons in Georgia, as well as the leaders of the Free Alabama Movement, a group that helped call for a 2016 national prison strike and organized several work stoppages within the Alabama prison system. Several guards beat alleged strike leader Terrance Dean unconscious after the Georgia strike. “The system is not a game to be played with,” Eddie said. “The one thing [JLS] always said was don’t put your face out there, don’t put your name out there under any circumstances because if we’re doing five or 10 years [in a] supermax, there’s nothing [the public] can do” to prevent reprisals.

The strikers’ demands, which Eddie described as “the immediate problems we have right now,” include better-funded rehabilitation services, reinstating Pell grants, an end to racist gang-enhancement laws, an end to prison slavery, restoring the voting rights of all confined citizens, and an end to the racial overcharging, over-sentencing, and parole denials of Black and brown people.

“For us, it’s just a matter of life and death actually, just to be blunt. That’s kind of where we’re at.”