The Case for Temporary Guaranteed Income for Formerly Incarcerated People

Temporary guaranteed income would provide the economic stability necessary to make reintegration more likely while providing benefits to taxpayers.

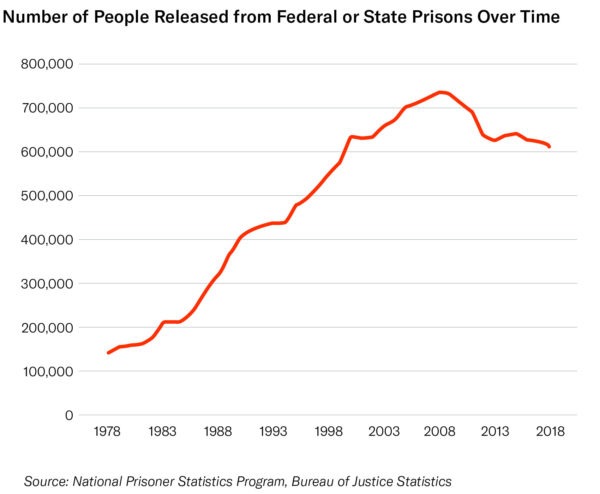

Over 600,000 people are released from U.S. prisons each year, up from about 158,000 in 1980. Along with the notable rise of mass incarceration, we have witnessed massive growth in the number of people exiting prisons and reentering communities across the nation. Unfortunately, reentry rarely equals reintegration. This population of formerly incarcerated people faces significant structural barriers to success, often leading to severe poverty and additional periods of incarceration. In particular, those who have been to prison suffer from Depression-level unemployment rates, homelessness that far outpaces the general public, and a three-year re-arrest rate of 68 percent. In this way, the United States’ reentry system reflects a sustained failure of federal, state, and local policy.

Fortunately, policymakers have practical tools to address the artificially manufactured barriers to reintegration that formerly incarcerated people face. One such tool is to provide a temporary guaranteed income (TGI) directly to those exiting prison as a transitional buffer against the inherent vulnerabilities created by reentry. Shown to be effective in a range of contexts, TGI would provide the economic stability necessary to make reintegration a more likely outcome while also providing positive social and fiscal benefits to taxpayers.

The Problem of Reentry

In 1980, fewer than 330,000 people were incarcerated in prisons across the United States. Today, that number has risen to almost 1.5 million, with a prison incarceration rate of about 639 per 100,000 – far outpacing the rest of the world. Similarly, because nearly everyone leaves prison, the number of releases over this period has also increased (by roughly 284 percent) to over 600,000 per year and current estimates suggest that nearly 5 million living people have been to prison at some point in their lives. While prison release is widely viewed as a “second chance” opportunity, the collateral consequences associated with incarceration and criminal records often preclude formerly incarcerated people from accessing essential resources that would otherwise lead to social and economic stability.

Nationwide, nearly 45,000 legislative policies regulate the lives of people with criminal records. These policies operate to ban this population from jobs, disqualify them for loans, regulate where they can go or live, and determine their access to a host of opportunities and resources that are otherwise available to United States citizens.

One of the most significant reentry-related issues is the remarkably consistent pattern of recidivism across time and space. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, roughly 44 percent of people exiting U.S. prisons are rearrested within just one year, while 68 percent are rearrested within three. Both community supervision and socioeconomic factors appear to play significant roles in shaping such high recidivism rates.

For example, roughly 25 percent of all prison admissions are due to a technical violation of community supervision, such as missing an appointment with a parole officer or failing a drug test. Rather than assisting people with the transition out of prisons, contemporary parole supervision focuses on heightened surveillance and enforcing behavioral conformity. Most people released on parole must abide by numerous conditions that may include passing drug tests, refraining from contact with others who have criminal records, attending anger management therapy, regularly meeting with parole officers, and abiding by curfews. Violating these conditions can—and often does—lead to re-arrest and incarceration, even though such behaviors would not normally result in imprisonment among people who are not on parole supervision.

Additionally, a range of social and economic factors directly impact recidivism. Gainful employment, in particular, plays a significant role in shaping post-imprisonment trajectories. But formerly incarcerated people face Depression-level unemployment rates of almost 30%. Part of the problem is that very few people leaving prisons have the skills or credentials necessary to make them attractive to employers (particularly as employers have required more skills and credentials relative to previous decades).

Furthermore, numerous studies have demonstrated that employers actively discriminate against individuals with criminal records, regardless of their human capital. In a series of audit studies, sociologist Devah Pager and colleagues sent out trained job “applicants” who varied only on race and the presence or absence of a criminal record (e.g., each job applicant was given a fictitious resume with the same educational and work history). These studies repeatedly showed that a criminal record reduced the rate at which employers called applicants back for interviews by about half, while also demonstrating that Black applicants with criminal records face the greatest amount of labor market discrimination.

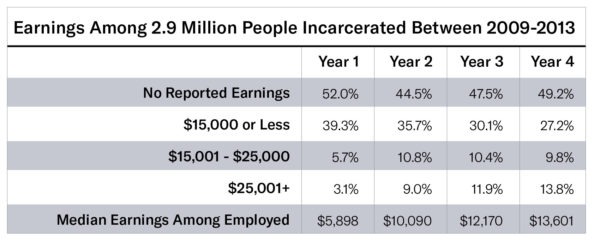

Even when formerly incarcerated people find employment, they are typically relegated to the most precarious jobs. According to a recent analysis of IRS data, roughly 52 percent of formerly incarcerated people reported making no earnings in the year following release. Of those who did report earnings, the vast majority made less than $15,000.(((It is important to note that criminalization tends to exacerbate already existing labor market disadvantages. Most people entering prisons had already experienced high levels of poverty prior to prison. Reentry, then, should be conceptualized as one component of a larger cycle of disadvantage. This proposal seeks to interrupt such cycles through TGI. ))) Notably, research suggests that these labor market difficulties contribute to the high rates of recidivism we observe nationally.

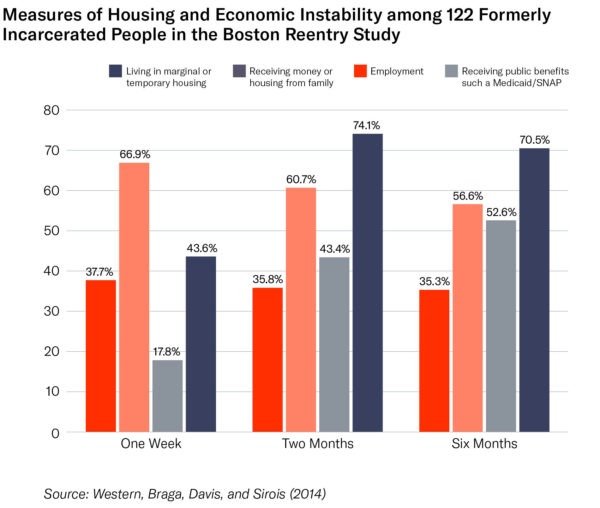

Beyond recidivism, however, the economic disadvantages experienced by formerly incarcerated people illustrate how the reentry process undermines overall wellbeing. In one example from a state with relatively generous reentry supports, researchers conducting the Boston Reentry Study documented overlapping social and economic hardships among a sample of formerly incarcerated people:

High rates of unemployment, medicaid and SNAP receipt, and housing insecurity suggest that the reentry process, particularly in the most immediate stage (when the risk of recidivism is also highest), presents numerous structural barriers to success. Along with these obstacles, people exiting prisons also face markedly higher rates of infectious disease, substance use disorder, serious mental health issues, and even death, compared to the general public; illustrating the need for greater access to health and social services.

Unfortunately, many of these issues go unaddressed due to the piecemeal nature of reentry service provisioning and the precariousness of post-imprisonment life. The following section addresses how a broad-based temporary guaranteed income (TGI) program would improve the wellbeing of formerly incarcerated people, while simultaneously benefitting the general public through long-term cost savings and enhanced public safety.

The Case for Guaranteed Income

Reentry support in many communities is limited and overtaxed, and where substantial resources do exist, they are largely filtered through fragmented nonprofit programming aimed at addressing human capital and behavioral issues. These inconsistent and often complicated webs of reentry provisioning lead to inefficient delivery and the underutilization of important services. Further, the broad emphasis on individual-level deficiencies, such as inadequate skills, motivational issues, or “thinking errors”, neglects various structural barriers to reintegration—like widespread racial and criminal record discrimination—while placing significant demands on ex-prisoner time.

While it is true that many people exiting prison would benefit from job skills, credentials, and various forms of therapy, these (often mandated) interventions may conflict with more immediate needs such as housing and income. For example, consider a formerly incarcerated person made to attend twice-weekly anger management classes as a condition of their parole supervision, while simultaneously lacking the ability to afford stable housing. In this scenario, more immediate housing and income-related needs may outweigh the mandated (and even the desire to attend) therapy; ultimately increasing the risk of a parole violation.

On the other hand, if the individual on parole attends their mandated anger management classes, it is not difficult to imagine how each session might reallocate valuable time away from housing and job searches (or jobs themselves). Even when reentry services are not mandated—as in the case of voluntary skills training programs—investing time into human capital development can be viewed as a risky proposition for those who are systematically excluded from decently paying occupations.

There is, however, a simple yet powerful policy solution that would help to alleviate the problem of overlapping reentry barriers: providing a temporary guaranteed income (TGI). For those leaving prisons, unrestricted direct payments would ease the immediate economic burden of reentry, while providing formerly incarcerated people with the personal stability necessary to address their unique combination of needs.

The most recent evidence for the positive impact of guaranteed income comes from the Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration (SEED). SEED provides $500 per month for two years to 125 randomly selected residents of Stockton, CA, who reside in neighborhoods with below median income ($46,033). In a one-year follow-up study, researchers found that those who received the cash assistance reported improved mental health, greater financial stability, and were actually more likely to find a full-time job compared to those who did not receive cash assistance.

Participants used the guaranteed income primarily to pay for household necessities (such as food, utilities, and transportation) and as a buffer against economic precarity. Additionally, the cash payments allowed participants to complete “internships, training, or coursework that lead to full-time employment or promotions.”Whereas many low-income individuals survive on a patchwork of temporary and inconsistent jobs that impede their ability to invest in themselves, the SEED experiment demonstrates that a steady income supplement allows individuals to focus on developing their skills and attaining credentials that would make them more successful in the labor market. Receiving guaranteed income payments provided SEED participants with more time and increased their ability to plan for the long term. According to the report authors, “as bandwidth increased, capacity for risk-taking, new goal setting pathways, and some freedom from forced vulnerability emerged.”

A host of other guaranteed income experiments are being proposed or are currently underway, such as Y Combinator’s Basic Income Experiment and various city-level pilots affiliated with Mayors for a Guaranteed Income. One such program, The Magnolia Mother’s Trust, which provides $1000/month to Black mothers living in Jackson, MI, saw substantial improvements in participant ability to pay bills, take advantage of educational opportunities, and seek professional medical help for health issues—demonstrating the positive impact on personal agency that direct cash payments can make.

For formerly incarcerated people, a guaranteed income would provide many of the same benefits, including less income volatility, improved physical and mental wellbeing, and a greater ability to take advantage of educational opportunities. Additionally, a more consistent income would reduce the inherent contradictions imposed by overlapping reentry demands. TGI would increase the capacity of formerly incarcerated people to work on individual-level issues (such as substance use disorder, serious mental health problems, or a lack of skills) while mitigating more immediate, economic-based needs such as food and housing.

For the wider community of taxpayers, guaranteed income for formerly incarcerated people would also provide fiscal benefits. According to the Vera Institute of Justice, the average yearly cost of incarcerating just one person (adjusted to 2021 dollars for inflation) amounts to nearly $38,000/yr. By comparison, $500-$1000 monthly cash payments would aggregate to $6,000-$12,000/yr (not including administrative expenses). Combined with evidence that a more stable income would improve the capacity of individuals to address their unique barriers to reintegration, the cost difference between guaranteed income programs and incarceration implies potentially significant taxpayer savings as fewer formerly incarcerated people return to prison after release.

Implementing Guaranteed Income for Those Exiting Prison

Despite empirical support for financially assisting those leaving prisons, practical concerns around implementation remain significant: Where might policymakers find the money necessary to fund such a program? For how long should payments be made? And should payments come with conditions?

To be sure, many of the answers are context dependent. Each prison across the U.S. is part of a larger federal or state correctional system, which is then embedded in yet a larger governmental structure with specific budgetary constraints. The disaggregated nature of our correctional and governmental bureaucracies prohibit a one-size-fits-all approach. However, there are strategies that would facilitate smooth implementation in a range of contexts:

- Implement TGI as an equity provision within marijuana legalization. The Congressional Research Service estimates that legalizing marijuana nationally would result in nearly $7 billion in tax revenue. From 2014 to 2017, Colorado alone collected six hundred million dollars in tax revenue from the sale of legalized marijuana. As a population that has historically faced criminalization for the possession, consumption, and distribution of an increasingly legal substance, funneling tax revenue to formerly incarcerated people would minimize the short-term economic burden of TGI and repair a semblance of the harm done by the war on drugs. States should conceive of marijuana legalization and equity provisions as components of a justice reinvestment strategy aimed at reducing crime, economic costs, and over-criminalization.

- Implement TGI as a transitional buffer: As the name implies, TGI is conceptualized as a transitional provision aimed at easing the reintegration process. Since ample social, economic, health, and recidivism data suggests that the first year post-release presents the highest risk for negative outcomes, states should consider distributing TGI payments for a minimum of twelve months.

- Determining TGI payment amounts: Recent guaranteed income experiments have varied in the amounts paid to recipients, but have typically clustered around $500-$1000/month. Rather than making ambiguous decisions around TGI payments, states should consider minimum payment amounts of $500/month and adjust upward for state-specific costs of living. States should also ensure that TGI recipients are not penalized or disqualified from receiving other forms of assistance for which they qualify. For example, to address this issue, project leaders from the SEED program pursued waivers exempting guaranteed income payments from being included in benefit eligibility calculations.

- Distribute TGI payments unconditionally: It is often assumed that conditional assistance best supports behavioral change, yet research suggests that these paternalistic forms of aid may actually inhibit positive outcomes, increase administrative costs, and promote widespread stigma. Further, poor households receiving direct cash payments tend to spend primarily on basic necessities such as housing, food, and personal hygiene items. As conceived in this proposal, TGI’s primary goal is to improve agency and self-sufficiency. That is, TGI’s greatest benefit lies in its ability to provide formerly incarcerated people with the time and economic stability necessary to work on the personal goals and issues of their choosing. TGI payments should be made unconditionally, as a temporary aid designed to promote long-term self-sufficiency, not as a tool for short-term behavioral compliance.