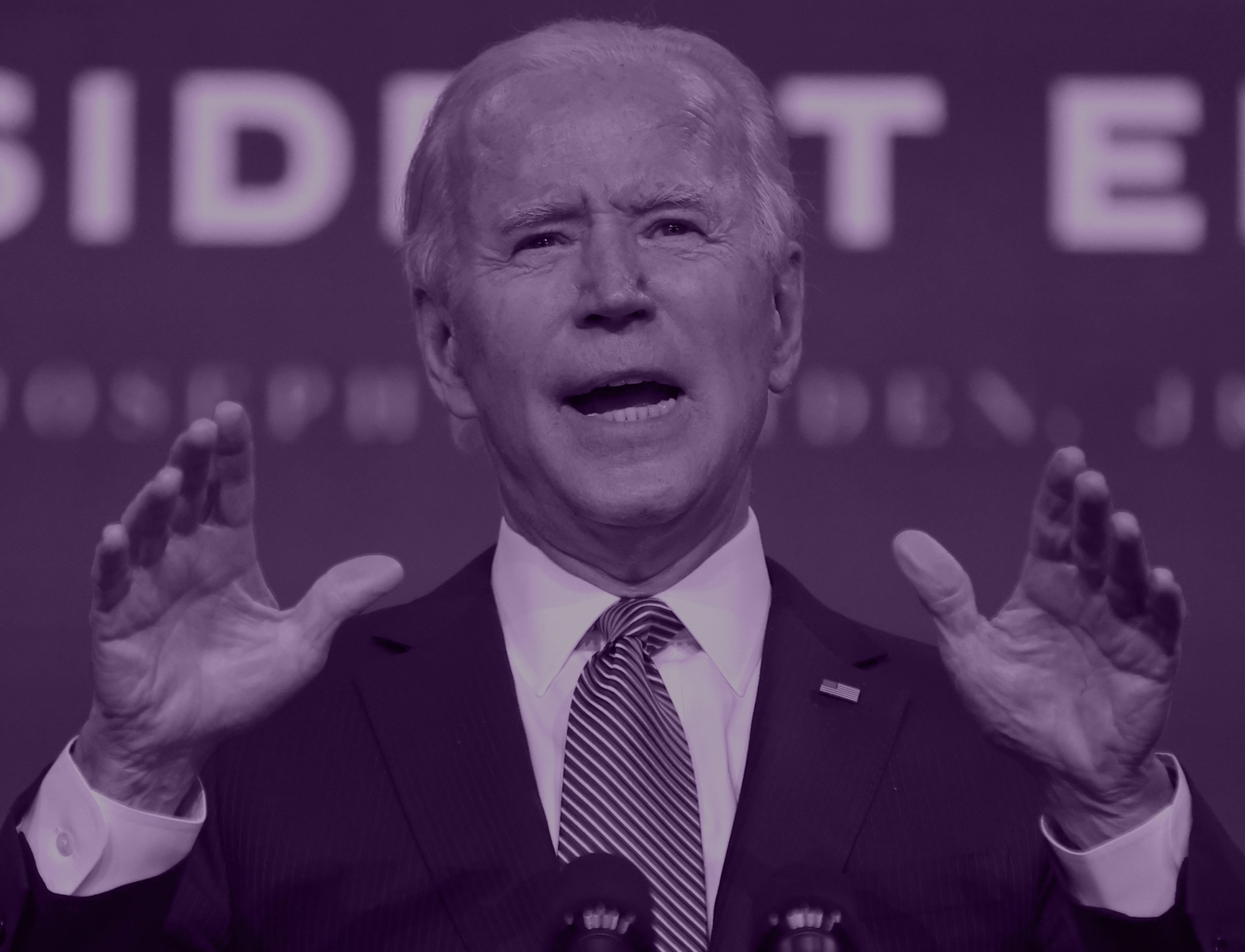

How Joe Biden Can Fix The Broken Clemency Process

There is also a growing bipartisan consensus that we send too many people to prison for too long, and clemency is one tool that can be used to limit the carceral state. Unfortunately, the process by which clemency petitions are evaluated is fundamentally broken.

Executive Summary

Presidential clemency is the constitutional process for national forgiveness. That forgiveness is urgently needed, as nearly 20 percent of the federal prison population is now over the age of 50 and has effectively aged out of commiting crime. There is also a growing bipartisan consensus that we send too many people to prison for too long, and clemency is one tool that can be used to limit the carceral state. Unfortunately, the process by which clemency petitions are evaluated is fundamentally broken. That process has failed many presidents, and it has failed the people confined to federal prison well beyond the time there was any conceivable reason to keep them there. Because of this broken process, the number of people who receive grants of clemency has significantly declined.

Clemency is one of the broadest areas of executive power afforded to any president. Article II, § 2, cl. 1 of the U.S. Constitution vests the president with the “Power to grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offenses against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment.” This unambiguously broad grant of power to the president makes clemency a uniquely powerful tool to ensure that the enforcement of criminal law reflects the president’s priorities while allowing the president to ameliorate both systemic and individual miscarriages of justice.

Presidential pardons were once commonplace, even frequent. But over time, the exercise of this power has been constrained and stymied by artificial bureaucracy within the U.S. Department of Justice, even though the Constitution reserves the clemency power as the “prerogative for the president alone to exercise.” A reorganization of the clemency function would allow the president to reassert their authority to the fullest extent consistent with the Constitution and more directly fix injustices inherent within the criminal legal system.

The causes of modern-day pardon paralysis are two-fold. First, the placement of the clemency process within the Department of Justice allows prosecutors too much influence—sometimes amounting to veto power—over decisions in individual cases. And these are cases in which the DOJ has an obvious conflict of interest, with prosecutors asked to second-guess the very sentences they themselves sought. Second, the process is grossly bureaucratic, requiring multiple layers of review—often by people with little criminal law experience—before a clemency petition even reaches the president.

Because these problems strike at the structure of the current process, the president should fundamentally reorganize it. The task of evaluating clemency petitions should be moved to an independent board of advisers chosen by the president outside the DOJ but within the White House. By placing responsibility for assessing clemency requests with such a board, a president can assert his full constitutional authority, streamline the process, remove any actual or perceived conflicts of interest, and enhance the objective assessment of individual cases.

Why Care About Clemency?

Article II of the Constitution makes it clear that the power to grant clemency is a core presidential power. The framers’ only limitation on the clemency power was to prevent its use in cases of impeachment.

Clemency is a vital part of the separation of powers. It allows a president to check both the legislative and judicial branches. When President Thomas Jefferson viewed the Alien and Sedition Acts as unconstitutional, his response was to pardon all those incarcerated under the Acts. The clemency power also allows a president to correct decisions of prior administrations with which the president disagrees. The clemency power thus allows the president to direct criminal justice policy without legislation.

A robust clemency power is essential to fairness in the criminal justice system. Previously, federal parole could address a variety of systemic and individual injustices arising from criminal prosecutions, such as wrongful convictions, overly harsh charging and sentencing determinations, and prison terms that extend well beyond the need for rehabilitation. But with the elimination of federal parole in 1984, there is no process for releasing those in federal prison who, through their rehabilitative efforts, no longer pose a threat to public safety. By reinstituting a forward-leaning clemency process, the system can more easily recognize those deserving of mercy.

Pardons are also critical to reintegrating the formerly incarcerated into society. A felony conviction dramatically reduces employment opportunities and earning potential. There are approximately 45,000 collateral consequences of a felony conviction imposed by federal, state, and local governments, ranging from the right to vote to access to housing. A full pardon can eliminate these consequences, and without it, economic and social opportunities for those who have supposedly paid their debts to society are foreclosed. At the same time, our economy is often deprived of an important source of labor: people coming out of prison.

The Current Process Is Broken

Under the current process, a clemency petition can be blocked anywhere along a lengthy line of decision points. It’s a system with a built-in bias against granting any form of clemency.

Currently, the Office of Pardon Attorney (OPA), located in the DOJ, gathers information and makes a recommendation on each individual clemency petition. Staff at OPA are required at the outset to seek the opinion of the local prosecutor who pursued the case. If that prosecutor recommends a denial, then petitions often receive negative recommendations at that point. The prosecutor can recommend a denial even though he or she might not have seen the clemency petitioner for decades while the petitioner was incarcerated in federal prison.

At the second step, the Pardon Attorney makes a recommendation. If the pardon attorney says no, the clemency petition will likely later die. The third stop is the desk of a staffer for the deputy attorney general (DAG), who does yet another review. The fourth stop is the DAG themself, who essentially supervises all criminal prosecutions at the DOJ and is a liaison between main DOJ and prosecutors. The DAG is probably the least likely person to second-guess the local prosecutor who recommends a denial, given the close working relationship between the DAG and prosecutors in the federal districts. By the time a recommended denial gets to staff of the White House Counsel, any hope for clemency is gone. The White House Counsel’s office has many other responsibilities, and it does not have the time or resources to run a full-blown clemency second-look operation. White House Counsel conducts the final review, with only favorable recommendations being presented to the president.

There are numerous problems with this process. First and foremost, it allows the DOJ to thwart the president’s clemency prerogatives. This is exactly what happened in the Obama Administration. President Barack Obama set criteria for his clemency power and his pardon attorney made numerous favorable recommendations. But his deputy attorney general, Sally Yates, overruled the pardon attorney’s favorable recommendations in many individual cases, and “secretly kept from the White House the contrary opinions of the DOJ Pardon Office.” Obama was not the only president to have his clemency power thwarted: As law professor Rachel Barkow observed, President George W. Bush “explicitly complained that he was not being provided with [clemency] grant recommendations when he sought them and urged President Obama to focus on fixing the clemency process.”

The current process poses an inherent conflict of interest; as Heritage Foundation scholar Paul J. Larkin Jr., has noted, “the current system leaves too much authority over clemency petitions to the Justice Department, the very agency that prosecuted every federal clemency applicant.” On occasion, the president and DOJ have different policy perspectives as to criminal legal issues, and, under the Constitution, the president’s views should prevail. Bringing the clemency process within the White House’s domain is the only way to ensure that the president’s prerogatives take precedence over those of the DOJ.

Even when the DOJ upholds the president’s policy prerogatives, the process is needlessly bureaucratic, requiring many rounds of sequential review by at least some people with little expertise in criminal law. For a single clemency petition to be granted, essentially seven different deciders must either agree on a favorable recommendation or at least move the petition to the next reviewer—seven people who institutionally have no consistent interest in doing so. There is a reason why successful businesses eschew this sort of vertical, sequential decision making in favor of horizontal decision making by boards.

Going, Going, Gone

Our country has a long history of both presidents and governors exercising executive clemency powers, often to “ordinary people for whom the results of a criminal prosecution were considered unduly harsh or unfair.” At the founding, most state governors possessed a restricted clemency power that was either limited in scope or subject to override by the state legislature. The Founders rejected all such restrictions when drafting the president’s clemency power, prohibiting only the granting of pardons in cases of impeachment.

Prior to the Civil War, grants of clemency were frequent, and the process was generally informal. Between the late 1800s and 1930, clemency was granted, on average, 222 times per year with 27 percent of applications receiving some form of relief. But despite the sweeping scope of the clemency power, grants of clemency have drastically decreased in recent decades. The creation of a more formalized pardons process caused a steep downward trajectory in clemency grants. Recent presidents have granted between 5-10 percent of these requests, with George W. Bush granting only 2 percent.

More disconcerting is the fact that while pardons and commutations have dropped precipitously, the number of federal crimes—and those convicted in federal courts—have grown by order of magnitude. When viewed in this context, the incredibly low number of granted petitions further highlights the inequitable balance and inefficiency of the current system.

Solutions

Restoring the president’s clemency power requires a fundamental reorganization of the clemency process. President-elect Joe Biden should move the Office of the Pardon Attorney into the Executive Office of the President (EOP) and create an independent advisory board that serves at the president’s pleasure. This reorganization will remove unnecessary bureaucratic layers of review that impede the president’s use of his clemency power, resolve the conflict of interest inherent in the current structure, and provide the president with greater agency in using the clemency power to enforce his values and priorities.

Why the EOP?

Clemency supervision should reside in the Executive Office of the President because the Constitution expressly vests the power in the chief executive. Removing the clemency process from under DOJ’s direct control also resolves the inherent conflict of interest of placing federal prosecutors in charge of second guessing their department’s own prosecutorial decisions. And moving the process to the White House better allows the president to establish and enforce his own set of priorities and preferences regarding how they want to employ the clemency power.

Composition and Structure

An independent advisory board is needed for several reasons. First, an advisory board eliminates the conflict of interest created by housing much of the clemency process within the DOJ.

Second, an independent board could mitigate any political concerns with using the clemency power. While the politics of crime have substantially shifted from the peak of the era of mass incarceration more than a decade ago—when each party wanted to look tough on crime—a bipartisan independent advisory board would insulate a president from whatever political concerns remain.

Third, an independent advisory board can provide the president with input from an array of important perspectives, many of which are missing in the current structure. The board should include representatives from a wide range of interests—not just current and former prosecutors. This could include public defenders, judges, probation officers, victims of crime, criminologists, academics, formerly incarcerated individuals, and policy experts. The board should be politically balanced with the shared, bipartisan goal of executing the president’s vision for his clemency power. And, of course, the board should receive significant input from the DOJ.

The board should also create reports and maintain data on the individuals given a grant of clemency, what charges they were convicted of, and whether they recidivated upon release. This structure would allow for data-driven clemency that focuses on promoting consistency and fairness in law enforcement. Capitalizing on their diverse perspectives, the board would be able to recommend many individuals for the president’s review, unencumbered by potential conflicts of interest that make for inconsistency in the review process.

Conclusion

There’s little dispute that the clemency review process is broken. It is bureaucratic and non-transparent, with a built-in bias against the granting of pardons or commutations. As a result, this broad presidential power has been artificially and unnecessarily constrained by the DOJ.

At its core, reforming the system must at the very least involve removing the Office of Pardon Attorney from the DOJ and removing the DOJ’s ostensible veto power over the process. The establishment of a bipartisan board to advise the president and make recommendations would not only improve the efficiency of the process, it would also bolster the public’s confidence in it. And by doing so, the new process would offer the president more opportunities to grant mercy and forgiveness to those who are worthy of it.