The Case For Moving Beyond Probation, And How To Do It

Radical change requires developing alternatives to probation that do not steer people into prison.

Probation is a problem masquerading as a solution. A core part of the American criminal legal system for more than 50 years, probation has created steady pathways into prison for an enormous percentage of incarcerated people. It is a key reason why only a handful of criminal cases are decided by jury trial, the most democratic element of the criminal legal system, and it has eroded the “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard, a mainstay of liberty and a protection against government excess. And yet, probation remains a popular option for addressing the crisis of mass incarceration.

In the campaign to reduce harsh sentences, it is easier to see probation for what it is not, rather than for what it is. The appeal of probation is both obvious and important: It allows people to remain in the community—taking their children to school, going to their jobs, and supporting their friends and family. Probation, in other words, is understood as “not prison.” Its attractiveness as a supposed alternative creates understandable pressure for individuals to bargain away their rights in a guilty plea. On a wider scale, the same pressures make expanding probation—or using probation as a default sentence—an alluring proposal in the drive for reform.

But probation is already the default sentence. It is not a path to transformation. Mass probation and mass incarceration are part of the same cycle.

Instead, the most promising opportunity to reduce mass incarceration—along with many other problems plaguing the criminal legal system—is to reduce the number of people on probation. Radical change requires developing alternatives to probation that do not steer people into prison. We need alternatives that disrupt, rather than facilitate, the carceral state.

Probation Corrupts the Rehabilitative Agenda

Devised to attack the root causes of crime through rehabilitation, probation once promised to keep people out of prison and reduce recidivism. In practice, however, the conditions of probation are arbitrary and burdensome, leading to high levels of control and surveillance. For example, a supervising officer is charged with ensuring that the person on probation abides by an average of 10 to 20 conditions a day, many of them designed to control non-criminal behavior. Often, these conditions have nothing to do with addressing the underlying needs of the individual, and in many cases, they create new hardships. The judges and law enforcement administering probation have too much discretion to set conditions that define and enforce their own version of “rehabilitation,” a slippery concept in the best of circumstances.

Not only are people assigned a litany of rules, they are given few meaningful resources to follow through on requirements that may last for many years. Vast numbers of people placed on probation will return to prison not for new offenses, but for violating the conditions of their release, often due to economic or health difficulties. Instead of offering stability and opportunities for advancement, probation too often functions as a trap, keeping people—and disproportionately Black people—under system control and locking them up when they cannot comply. In these circumstances, probation serves as a force for debilitation, not rehabilitation.

Too Many People Are Already on Probation

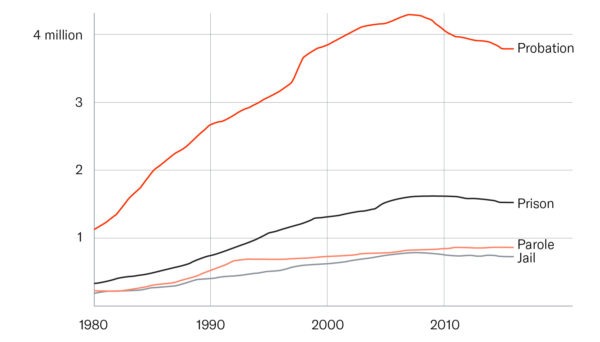

More people are sentenced to probation than any other form of criminal legal sanction. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, by the end of 2018, 3.54 million people were on probation. By contrast, approximately 1.6 million people were serving a sentence in U.S. prisons and jails. (Most people in jail are held pretrial, which means they have not been convicted.) The graph below, from a new report by Human Rights Watch and the ACLU, demonstrates the extent to which criminal courts have imposed probation as the dominant outcome over many decades.

These numbers show why sentencing even more people to probation will not transform the criminal legal system. As the prison population has skyrocketed, the probation population has grown even more. Mass probation has flourished in symbiosis with mass incarceration.

Too Many People on Probation (and Parole) Go To Prison

Probation is not a disruptor of prison. Instead, probation—and its close cousin parole—draw staggering numbers of people into prison. In 2019, the Council of State Governments reported that 23 percent of state prison admissions nationwide are due to violations of probation. Violations of parole, a form of community supervision that comes after a prison sentence, separately account for 22 percent of state prison admissions. To the extent that community supervision mechanisms like probation and parole are supposed to be alternatives to prison, they are failed alternatives: They account for 45 percent of prison admissions in states around the country.

Moreover, roughly half of this figure is attributable to technical violations, such as missed appointments, broken curfews, or failed drug or alcohol tests. Technical violations of probation account for 11 percent of all state prison admissions, and technical violations of parole account for 14 percent of state prison admissions. Together, the non-criminal rules of probation and parole pull roughly 1 in 4 people into state prisons.

Probation Undermines Core Legal Protections

Mass probation has also perverted criminal procedure and diminished important protections for accused individuals. In a 1968 case, the U.S. Supreme Court emphasized that jury trial is a right granted to criminal defendants in order to prevent oppression by the government. The Court explained that “providing an accused with a right to be tried by a jury of his peers gave him an inestimable safeguard against the corrupt or overzealous prosecutor and against the compliant, biased, or eccentric judge.” But today, 94 percent of state court convictions are the result of guilty pleas. All those who plead guilty forgo their right to a jury trial, and most plead guilty in exchange for the promise of probation, not for a reduced term of incarceration.

Probation has long functioned as the engine of guilty plea culture. Probation originated in Massachusetts in the first half of the nineteenth century as a way to grant prosecutors (and later judges) more power to control case outcomes. The legal foundations of probation involved an exchange: a person would agree to plead guilty to a crime in exchange for a promise that the person would not go to prison as long as they followed the rules set by the prosecutor and/or judge. It turns out that a number of psychological factors encourage people to accept almost any condition of probation in exchange for the promise of avoiding prison. Because people discount future risk, for example, they will put themselves at great risk of incarceration in the future to secure a promise that they will not go to prison today. These psychological dynamics help explain why so many people “agree” to be bound by broad and intrusive conditions that make them so vulnerable to incarceration as soon as they go on probation.

For prosecutors, having someone “on probation” makes it much easier to charge and punish that person going forward. Most Americans are familiar with the “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard, which requires the prosecution to prove its case to a high bar of certainty before a person can be found guilty. But once a person agrees to plead guilty in exchange for probation, the prosecutor no longer needs to prove future violations of probation conditions “beyond a reasonable doubt.” Instead, violations (whether technical or criminal) need only be established by a preponderance of the evidence or sometimes much less. These shifts in the burden of proof are deeply significant: The “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard is the main instrument for protecting the presumption of innocence, and it helps validate the moral force of the criminal law.

Probation also creates too many opportunities for low-visibility abuse by law enforcement. A person on probation meets privately with their probation officer, who is given a great deal of discretion and decision-making authority in determining whether a person has adequately complied with numerous conditions. The person under supervision generally has no ability to push back on a probation officer’s demands.

Considering the number of people on probation, these reduced protections and enhanced controls significantly undermine the criminal legal system as a whole.

Reevaluating Probation to Create True Alternatives to Prison

Probation in its current form cannot be saved. In place of a system that pretends to curb incarceration but only drives it forward, we need alternatives to prison that provide opportunities for better outcomes. Meaningful change requires taking steps that radically reduce our dependence on probation.

Shrink the Parameters of Probation

State legislatures can significantly reduce the probation population by declaring certain categories of offenses, including many misdemeanors, off limits for probation supervision and cutting the length of supervision terms so that they are measured in months, not years.

But this will only work if probation is not replaced by something that is even more punitive. Federal, state, and local government officials should enact alternatives to probation that do not provide mechanisms for funneling people into prison, such as unconditional discharges, flexible community service, or community-driven support systems. They should develop these alternatives in consultation with research from scholars, policy specialists, victims’ groups, and those who have spent time on probation. The research must be attuned to the expressive values (or symbolic meanings) that the public attaches to different kinds of sentences, while seeking to shape those values at the same time. Alternatives should function as determinate and proportionate punishments, not as vehicles for cyclical and discriminatory debilitation.

Increase Protections for Those on Probation

A different way to reduce the number of people on probation would be to raise the procedural protections that apply to revocation proceedings. Probation would be much less attractive to prosecutors if they could not rely on quick and easy hearings to convict people of violations.

By raising the procedural standards, policymakers could cut the probation population and improve the integrity of the adjudication process at the same time. State lawmakers could pass statutes requiring prosecutors to prove violations of probation beyond a reasonable doubt if they want to rely on those violations to send someone to prison. Courts could require that juries (rather than judges) weigh the evidence and resolve factual disputes to expand the democratic legitimacy of the revocation process. In a 2019 case, for example, the U.S. Supreme Court nullified a five-year mandatory minimum prison sentence that a trial judge had imposed in a revocation hearing. The Supreme Court found that the imposition of this mandatory minimum penalty—for a violation of a condition of supervision—had violated the defendant’s jury trial rights.

Given the expansive nature of modern conditions, enhanced procedural protections may not be sufficient to alter the dynamics of revocation. Revocation hearings often involve breaches of simple rules like failing to report on a schedule created by a probation officer. Violations of these kinds of rules are easy to prove under any standard.

Reform measures should therefore limit the kinds of conditions that can serve as the basis for custodial sanctions. Judges and probation officers should not be empowered to set conditions based on their own individual notions of what “rehabilitation” means. Courts should rethink their reliance on conditions, like drug testing conditions, that lack research support and reliably lead to over-incarceration and over-criminalization.

Provide Treatment Outside the Structure of the Criminal Legal System

Another method of reducing the number of people on probation would be to adopt a public health approach to treatment. Courts and legislatures should disentangle needed services (such as mental health counseling and drug treatment) from the threat of prison sanctions. Rather than placing everyone who needs treatment on probation, treatment could be handled outside the criminal legal system in a manner that better fosters reintegration and wellbeing. This approach could emphasize the continued delivery of treatment, as well as other services around education and employment, without using incarceration as a backstop. It would ensure that people would not be sent to prison if they were late to a treatment appointment or had difficulty overcoming an addiction on a timeline created by a court official with no public health expertise.

Laws that separate treatment from punishment would respond to longstanding criticisms of probation advanced by preeminent scholars of the rehabilitative model. Writing in 1981, for example, Francis Allen emphasized that in the “rigorous competition” between the rehabilitative and punitive purposes of U.S. sentencing over many decades, rehabilitation was generally “outmatched in the struggle” even when a sentence was said to be focused on rehabilitation. Rather than serving rehabilitative ends, the system deployed the language of rehabilitation to “camouflage punitive measures that might otherwise produce protest in the community.”

Lawmakers could move to a more public-health oriented approach by enacting a sweeping reform endorsed by EXiT, an influential group of probation executives. EXiT is pushing to end what it terms the “vicious cycle of reincarceration” for “administrative rule violations.” This group, which includes current and former heads of probation systems, recommends eliminating incarceration for all technical violations. A clear reform like this would have a far reaching impact, including by preventing law enforcement officials from using incarceration to enforce rules and expectations that they (rather than public health experts) have devised for treatment programs.

Conclusion

Probation creates open-air prisons. The lack of walls makes the punitive power of probation less visible and harder to grasp. Probation’s role in building the penal state is disguised so effectively that it can present itself in the role of a potential savior even as it grinds down legal protections and drives up incarceration. It is time for a new approach, one that focuses both on keeping people out of prisons and on improving individual outcomes and stability.