How the Supreme Court Has Turned False Narratives on Policing into More Police Power

Introduction Late one night in September 1980, New York City police officers chased Benjamin Quarles to the back of a grocery store. There, officers detained Quarles and frisked him, finding an empty shoulder holster. After securing Quarles with handcuffs, one officer asked him where the gun was. Quarles nodded toward some empty cartons and replied, […]

Introduction

Late one night in September 1980, New York City police officers chased Benjamin Quarles to the back of a grocery store. There, officers detained Quarles and frisked him, finding an empty shoulder holster. After securing Quarles with handcuffs, one officer asked him where the gun was. Quarles nodded toward some empty cartons and replied, “The gun is over there.”

Later, the Supreme Court decided whether Quarles’ statement could be used against him at trial. Ordinarily, once someone is in custody the police must provide Miranda warnings, advising the suspect of the right to remain silent, before starting an interrogation. But in New York v. Quarles the Court created an exception: police officers can freely question someone about an ongoing threat to public safety—in this case, a gun discarded in a grocery store waiting to be found—and any responses can later be used as evidence, even without a Miranda waiver.

In his majority opinion, Chief Justice William Rehnquist dispensed with concerns about creating an incentive for police to routinely disregard Miranda under the guise of public safety. Not to worry, he said, “police officers can and will distinguish almost instinctively between questions necessary to secure their own safety or the safety of the public and questions designed solely to elicit testimonial evidence.”

In dissent, Justice Thurgood Marshall called this “wishful thinking.” Instead, Marshall wrote, the new “public safety exception” to Miranda “expressly invite[s] police officers to coerce defendants into making incriminating statements.”

Marshall came at cases involving the police with unique experience. The Court’s first Black Justice, he had worked as a civil rights and criminal defense lawyer, often defending people in race- based prosecutions. As a Black lawyer working in the Deep South, Marshall had personally faced threats and intimidation from law enforcement, and stood shoulder-to-shoulder with clients who had, as Fourth Amendment scholar Anthony Amsterdam wrote in 1974, “seen the policeman from the nightstick end.”

On the Court, Marshall’s colleagues recognized the value of this perspective. “At oral arguments and conference meetings, in opinions and dissents, Justice Marshall imparted not only his legal acumen but also his life experiences,” Justice Sandra Day O’Connor later said.

And yet there hasn’t been a Supreme Court Justice with significant criminal defense experience since Marshall retired in 1991. Indeed, throughout the federal courts, and under both Democratic and Republican presidents, “prosecutor” has long been a common resume line among judges, while civil rights lawyers and public defenders have been the rare exception.

Quarles illustrates one result of this disparity: In many cases involving the police, the outcome turns on assumptions about policing that embed an attitude of trust and deference toward the police (and skepticism of civil liberties for the policed). As a result, criminal procedure jurisprudence has been imbued with a decidedly one-sided and often factually-flawed narrative of policing: that policing is supremely dangerous; that police officers, under siege and sacrificing for the public good, cannot be second guessed; and that even when fundamental constitutional rights are at stake the police are owed great deference and should be trusted.

It’s a vision of American policing—and a body of constitutional law based upon it—at odds with our national reckoning over police brutality and racism. Today, bodycam and cell phone videos of police officers killing defenseless Black people are ubiquitous. In some places, officers

lie in court so often officers call it “testilying.” One recent investigation documented racist and violent social media posts by officers across the country, and another showed that officers fired for misconduct by one agency are often rehired by another. There’s also growing consensus that police officers are ill equipped to handle many situations they are called to address, including people experiencing homelessness or mental health crises. Given this reality, Supreme Court opinions often read like decisions made in, and for, an alternate universe.

How can federal courts make better informed decisions? Decisions that consider not just the interests of police, but the often brutal reality of the people subject to their control? One (albeit incomplete) solution is both straightforward

and popular: Diversify the lived experiences of those sitting on the federal bench, including by appointing more public defenders and civil rights lawyers—legal professionals who have made a career of challenging rather than defending the police perspective.

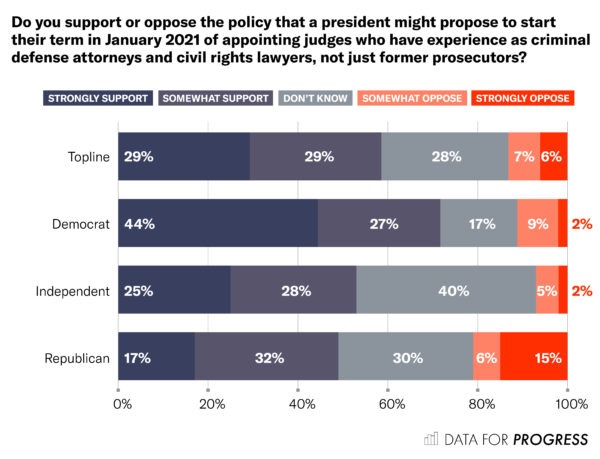

According to new national polling from Data for Progress and The Justice Collaborative Institute, 58% of voters—including about half (49%) of Republicans—support “appointing judges who have experience as criminal defense attorneys and civil rights lawyers, not just former prosecutors.”

Judicial Viewpoint and Building Police Power

One need not reject the notion that judges aspire to decide cases based on objective application of the law to understand that a judge’s background and experiences matter. Judges often have discretion to act within a range of possibilities, and must make judgment calls about the application of imprecise legal standards to the unique facts of every case. A substantial body of research shows that judges, like the rest of us, will perform those tasks while subject to a range of cognitive biases—described in one UCLA Law Review article as the brain’s “oddly stubborn tendency to anchor to … judgments, or assessments to which we have been exposed and to use them as a starting point for future judgments—even if those anchors are objectively wrong.”

When it comes to the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence governing policing, pervasive features of the Court’s decisions reflect and reinforce a “tendency to anchor to” perspectives that privilege and defer to police interests, at the expense of civil liberties. Two features of the Court’s decisions in this arena illustrate the point.

First, as former police officer turned law professor Seth Stoughton discusses in his article, “Policing Facts,” the Supreme Court’s Fourth Amendment decisions—which govern police arrests, searches, and use of force—frequently rest on untested, unsupported, and inaccurate or incomplete factual assumptions about how policing works in practice. These assumptions almost uniformly skew toward deference to police.

To begin with, Stoughton writes, the Court has declared “law enforcement … a dangerous business,” observing, for example, that “American criminals have a long tradition of armed violence” against police. The Court has also deemed certain police activity especially risky, including traffic stops, approaching stopped vehicles, and investigative detentions—characterizations that empirical analysis has shown to be inaccurate.

The Court also valorizes officers themselves, imbuing them with special talents and insights. On top of the “instinctive” abilities asserted in Quarles, the Court believes police can discern when even perfectly lawful conduct is a sign of imminent danger or criminality. With the “experience and specialized training” that officers receive, the Court has said, they can “make inferences from and deductions about the cumulative information available to them that ‘might well elude an untrained person.’” And the Court assumes that these abilities are generally used in good faith. According to the Court, “police forces across the United States take the constitutional rights of citizens seriously.”

But as Stoughton explores elsewhere, American law enforcement has adopted a “warrior” mentality, with officers trained to stay hyper- vigilant and treat every person as a lethal threat. With that approach, a frisk for weapons becomes an inevitable part of every stop, not the result of some specialized expert analysis.

This view of the police—perpetually under threat, highly skilled, well-trained, and committed to respecting civil liberties—gets baked into Fourth Amendment doctrine, whether in rules about searches and seizures or the use of force.

For example, faith in officer training and their intuition guides decisions on whether officers have “reasonable suspicion” to stop and frisk someone, or whether they have “probable cause” to conduct a search. On these issues, the Supreme Court has instructed courts to defer to the “experience and specialized training of the police.” But the finely- tuned “intuition” ascribed to officers can provide cover to target people randomly without cause— or, worse, based on their race or where they live, as we have seen in the destructive stop-and-frisk policing tactics deployed disproportionately in Black and brown communities across the country.

Similarly, when the Supreme Court reviews the police use of force, it insists that “police officers are often forced to make split-second judgments— in circumstances that are tense, uncertain, and rapidly evolving.” This court-created description of police work, first introduced in 1989, has been repeated in more than 2,300 judicial opinions. As a result, law professor Michael Avery has written, “many of the lower federal courts have become mesmerized by the concept that police officers are forced to make decisions about the use of force in split seconds.”

But as Stoughton explains, this assumption has little basis in reality. “The vast majority of the time,” Stoughton writes, “officers use force aggressively, not defensively. That is, they act forcefully to establish control over a suspect rather than to defend themselves, a third party, or the suspect from some imminent harm.” And “considering that the vast majority of use-of- force incidents involve the use of aggressive force by police officers … the Court’s description of ‘split-second judgments’ is simply wrong almost all the time.”

Second, another layer of law enforcement deference is the Supreme Court’s doctrine of qualified immunity. The Court invented this doctrine to protect police (and other public officials) from civil liability when they violate people’s constitutional rights. Officers get immunity unless there’s a prior case showing that their conduct was clearly illegal. The idea is that officers should have notice of impermissible conduct before they’re held liable for it, but the Court has increasingly raised this standard to near impossible levels. Again and again, the Court has rejected the claim that prior case law “clearly established” a rights violation unless the cases involve nearly identical facts.

While in theory police officers are expected to know that some conduct is unlawful “even in novel factual circumstances,” the Court has repeatedly admonished that “clearly established law should not be defined at a high level of generality,” and that courts should give police extra leeway when they are alleged to have used excessive force. In that context, “the Court has recognized that it is sometimes difficult for an officer to determine how the relevant legal doctrine … will apply to the factual situation the officer confronts.”

In other words, qualified immunity is a doctrine of extraordinary police deference, one that puts the costs of police brutality on the people who are victimized by it. The rule assumes that aggressive policing, including violence that pushes and even exceeds constitutional boundaries, is, on the whole, in society’s interest. In one dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor lamented that qualified immunity “sends an alarming signal to law enforcement officers and the public. It tells officers that they can shoot first and think later, and it tells the public that palpably unreasonable conduct will go unpunished.”

And lower courts have frequently proven Sotomayor correct. For example, this year the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals dismissed a civil rights lawsuit against a police officer who shot an unarmed man in the back after he broke away from the officer’s attempt to arrest him. Police had conducted a pat down that revealed no weapons, and the law was already clear that police cannot shoot a fleeing suspect unless they have reason to believe the person poses a risk of death or serious injury to the police or others. But that wasn’t clear enough. Instead, the court said, the officer was entitled to immunity because no prior decisions specifically said that police officers cannot shoot someone after a pat down reveals no weapons. Judge Jane Kelly, a former public defender, dissented.

Diversify the Branch

How did this empirically flawed and highly deferential view of policing take root?

In a 2016 article, law professor and criminal procedure scholar Andrew Crespo points to one explanation: “[I]n the [last four] decades … the Supreme Court has seen a threefold increase in the number of its Justices with experience working as criminal prosecutors prior to their ascension to the bench.” Indeed, as law professor Benjamin Barton’s prior research on Supreme Court justices has demonstrated, the Roberts Court represents an all-time low of justices with experience representing private clients at all (and the vast majority of that representation has been of corporations, not people). During that same time, the Court lost its only member “with direct familiarity of modern-day policing and prosecution, as they are so often experienced by the stopped, the frisked, the arrested and the accused,” when Justice Marshall retired.

This trend has also played out on the federal trial and appellate courts, where former prosecutors outnumber former public defenders four to one. For example, only 14% of President Obama’s district court nominees had worked in public defense, while 41% of his nominees had worked as prosecutors. President Trump’s record is even worse. Currently, only about 1% of appellate judges spent the majority of their careers as public defenders or legal aid attorneys.

The result is a judiciary with ample professional experience defending the poorly supported presumptions of law enforcement expertise and deference, and comparatively little (or, in the case of the Supreme Court zero) experience contesting those narratives and advocating for the interests of individuals who bear some of the most direct costs of law enforcement action. The point is not that former prosecutors or former defense attorneys are of one mind with regard to policing, or that judges’ views are the reductive product of their prior professional experience. Indeed, Justice Sotomayor, a former prosecutor in the Bronx, has led the charge against untested assumptions that defer to police and minimize the damage done by law enforcement practices. Nevertheless, experience matters.

Over the last few months, at the height of national protests against police brutality, we’ve seen what the impact of judges with different perspectives— different life experiences and different backgrounds—can look like.

In the Southern District of Mississippi, Judge Carlton Reeves, the second Black person to serve on the federal bench in Mississippi, wrote an impassioned plea for the Supreme Court to eliminate qualified immunity for the police. Reeves’ opinion opens with a long list of innocuous circumstances—walking home from work, driving with a broken taillight—under which police have killed Black people, and it details the history of state-sponsored violence against Black Americans from Reconstruction to the present, putting the Supreme Court’s failure to hold police accountable squarely in that context. The opinion challenges not just the doctrine of qualified immunity, but the false narrative of American policing that has driven Supreme Court decision making for decades, offering in its place an account grounded in the history and reality of racist police violence.

Conclusion

The vision of American policing reflected in the Supreme Court’s criminal procedure jurisprudence—a vision of expert crime-fighters under siege and deserving of judicial deference—is neither empirically grounded nor inevitable. It is a construct. And it should come as no surprise that a bench whose professional life has been overwhelmingly dedicated to defending, rather than contesting, the judgments of police would create such a construct. Diversifying the federal bench with lawyers that have insight into the perspectives of those who are the targets of law enforcement action is an important, and politically viable, corrective.

Polling Methodology

From October 30 to October 31, 2020, Data for Progress conducted a survey of 997 likely voters nationally using web panel respondents. The sample was weighted to be representative of likely voters by age, gender, education, race, and voting history. The survey was conducted in English. The margin of error is ±3.1 percentage points.