End Corporate Tax Avoidance and Tax Competition – Collect the Tax Deficit of Multinationals

Tax systems have too often worked toturbocharge the inequalities associated with our modern economy.

Introduction

(((A longer version of our arguments is available via SSRN here. This proposal solely reflects the authors’ views and builds upon previous tax reform ideas presented by the authors in book format for the broader public. See Clausing, Kimberly. Open: The Progressive Case for Free-Trade, Immigration, and Global Capital. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019 and Saez, Emmanuel and Gabriel Zucman. The Triumph of Injustice: How the Rich Dodge Taxes and How to Make them Pay. New York: W.W. Norton, 2019.)))In recent decades, governments have steadily lowered corporate tax rates in an attempt to gain jobs, investment, and tax base at the expense of other countries. Between 1985 and 2020, across the world, the average corporate tax rate fell from 49% to 23%. In the United States, the average effective tax rate on corporate profits has fallen from close to 50% in the 1950s to 17% in 2018.(((For statutory rates, see OECD Statistics, Statutory corporate income tax rates, weighted by GDP. For effective tax rates, see U.S. National Income and Product Accounts. Detailed statistics on tax rates relative to national income are compiled in Piketty, Saez, and Zucman (2018).)))

These dynamics cause workers to shoulder more of the tax burden associated with funding governments, even as economic changes in recent decades have brought declining labor shares of income (the share of GDP that is paid in wages) and large increases in income inequality. Unfortunately, instead of seeking to counter such trends, tax systems have too often worked to turbocharge the inequalities associated with our modern economy.(((Such shifting burdens are not just inequitable; they also interfere with the larger goals of an efficient and well-administered tax system. Since capital often goes untaxed at the individual level and capital income often represents rents–or excess returns to capital–adequate business taxation is essential for a fair and efficient tax system. In the United States, 70% of U.S. equity income is not taxed by the U.S. government at the individual level; see Burman, Clausing, and Austin (2017).)))

Further, international tax avoidance has also become a pressing problem. Corporate tax avoidance costs the United States government about $100 billion a year in lost tax revenue; these revenues could be a vital source of funding for many urgent priorities such as education, healthcare, infrastructure, or investments toward climate change mitigation.(((For several estimates on the size of U.S. government revenue lost due to international tax avoidance, see Clausing (2020): https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3274827.)))

We propose ending this race to the bottom in corporate taxation through a negotiated system of coordinated minimum taxation. Such negotiation takes time, but in the meantime, unilateral adoption of minimum taxes by large countries can help protect the corporate tax bases of both adopting and non-adopting countries. We also suggest steps for responding to non-adopting countries. (For additional detail, please see our full working paper.)

It is not an exaggeration to say that minimum taxes could change the face of globalization. With a high enough tax floor, the logic of international competition would be turned on its head. Once taxes are out of the picture, companies would go where the workforce is productive, infrastructure is high quality, and consumers have enough purchasing power to buy their products. Instead of competing by slashing rates, countries would compete by boosting infrastructure spending to make their locations an attractive place to move to, by investing in access to education, and funding research. Instead of focusing solely on the bottom line of shareholders, international competition would contribute to more equality within countries.

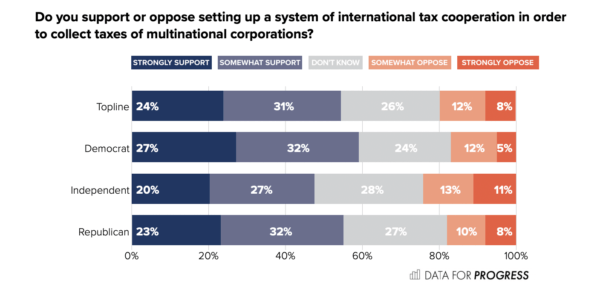

A recent national poll conducted by Data for Progress and The Justice Collaborative Institute shows strong bipartisan support for coordinated minimum taxation:

- 55% of respondents said they somewhat supported or strongly supported setting up a system of international tax cooperation, with only 20% somewhat or strongly opposed.

- Partisan differences were small. Among Democrats polled, 59% were somewhat or strongly in favor, and 17% were somewhat or strongly opposed, while among Republicans, 55% were somewhat or strongly in favor, and 18% somewhat or strongly opposed.

The Current Problem of Eroding Tax Bases

Multinational companies respond to disparities in corporate tax rates across countries by moving jobs and investment toward low-tax destinations and, to a far greater extent, by shifting paper profits toward their lightly-taxed subsidiaries, especially those incorporated in tax havens with rock-bottom tax rates. This is a large-scale issue. In 2017, for example, multinational companies that are headquartered in the United States reported offshore accumulated earnings of $4.2 trillion, of which $3 trillion was recorded in tax havens.(((Tax havens are jurisdictions with very low, often near zero, tax rates; a small number of havens are disproportionately important. For U.S. companies, just nine havens account for $2.8 trillion of the $3 trillion in haven earnings. Of these nine havens, four are independent European jurisdictions (Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and Switzerland), four are island jurisdictions with close affiliations to the United Kingdom (Bermuda, Jersey, and the Cayman Islands) or the United States (Puerto Rico), and the other is Singapore. The $3 trillion figure includes a broader group of smaller havens beyond those nine, including Isle of Man, Gibraltar, Macau, St. Lucia, St. Kitts and Nevis, Barbados, and Mauritius.)))

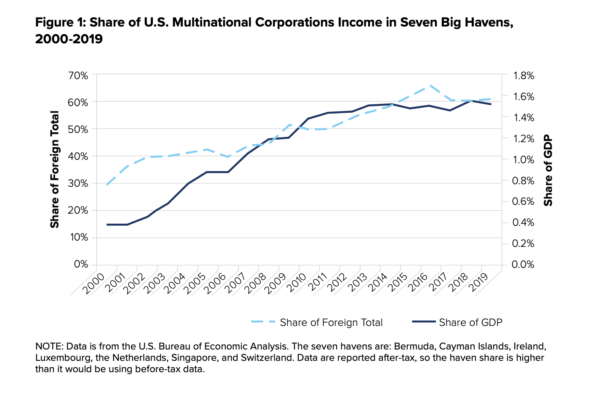

International attention on this issue led to a multi-year effort by countries party to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the G20 countries, to reduce profit shifting. While these efforts have resulted in many helpful guidelines and efforts, there is unfortunately little evidence that profit shifting is subsiding. In 2019 data, U.S. multinationals reported the same share of their foreign direct investment earnings in havens as they did in recent years.(((. The share of U.S. multinational company income booked in havens has been steady since about 2011, although it was rising steeply in years prior. For U.S. multinational companies, perhaps the OECD/G20 process reduced the increase in the size of the problem, but it does not seem to have diminished the problem yet. Likewise, the tax act of 2017 (TCJA) in effect in 2018 and 2019 does not appear to change these trends.)))

Exemplarity

Our plan has three pillars: exemplarity, coordination, and defensive measures against noncooperative tax havens. We illustrate our proposal using the United States as an example, but other countries could implement the same plan. Exemplarity means that the United States (and any country that wishes to do so) should collect the tax deficit of its multinationals, which we define as the difference between what a corporation pays in taxes abroad and what it would have to pay if taxed at the agreed minimum tax rate in each country.

Minimum taxation would mean that the United States would impose country-by-country taxes so that any U.S. multinational’s tax rate, in each of the countries where it operates, equals at least 21%.(((We use 21% since that is the current U.S. corporate tax rate; of course, other rates could be chosen.))) In other words, the United States would, for its own multinationals, play the role of tax collector of last resort: It would collect the taxes that foreign countries chose not to collect. For example, imagine that Apple books $10 billion in profits in Ireland—taxed there at 5%—and $3 billion in the British dependency Jersey—taxed there at 0%. The United States would then apply a minimum tax by taxing Apple’s Irish income at 16% and Apple’s Jersey income at 21%.

Applying minimum country-by-country taxes would have far-reaching consequences. With a high enough rate, this policy would remove tax incentives for U.S. multinationals to shift earnings or move jobs and investment to low-tax places, because lower taxes abroad would be offset by higher taxes owed in the United States. Moreover, since there would not be incentives anymore for multinationals to operate or book earnings in lowtax places, there would be no point anymore for these countries to offer low rates in the first place. Today’s tax havens would find it advantageous to increase their tax rates. In other words, with high enough country-by-country minimum taxes, the race to the bottom which has characterized globalization since the 1980s could be replaced by harmonization upward.

In our longer paper, we discuss the design issues of such a tax in detail. It is important, for example, that the United States (and other countries) apply such taxes on a country-by-country basis, especially if the minimum rate on foreign income is set below the normal corporate tax rate. It is also important that all foreign earnings be subject to the tax. The United States has tried a feeble minimum tax since 2018, but it does not tax all income, is set at a low rate, and allows tax credits from higher-tax countries and territories to offset minimum tax due, so is not expected to raise much revenue. Nor is there any sign of diminished profit shifting because of this tax. (See Figure 1.)

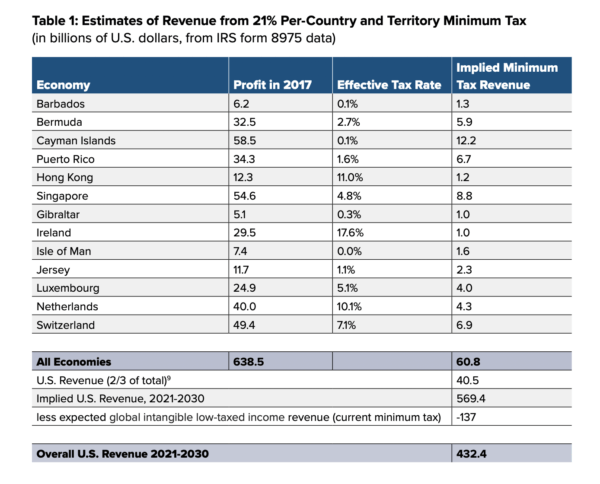

If the United States imposed a 21% country by-country minimum tax, it would generate a sizable amount of revenue. Table 1 shows the total revenues from such a tax, including detail on the 12 tax havens that, even by a conservative estimate, could each be responsible for more than $1 billion in minimum tax revenue in the United States.(((These estimates are conservative since effective tax rates abroad are likely to be overstated, and income understated, since companies with losses are included in this data series. For more detail, see the full working paper.)))

Not all of these revenues will ultimately be recorded as minimum tax revenues. Indeed, the point of the minimum tax is to discourage profit shifting, and collecting minimum taxes should cause the location of profits to more accurately reflect the location of economic activities. Thus, the revenues in Table 1 are the total effect of both minimum tax revenue and the growing corporate tax base that can be expected as profit-shifting decreases.

(((Because a minimum tax will reduce profit shifting from all jurisdictions toward tax havens, some of the income that would have been shifted by U.S. multinational companies from other foreign countries to tax havens “belongs” to those countries rather than the United States. We assume 2 /3 of the excess haven income truly belongs to the United States, since about 2 /3 of U.S. multinational company economic activities are based in the United States. )))

(((Because a minimum tax will reduce profit shifting from all jurisdictions toward tax havens, some of the income that would have been shifted by U.S. multinational companies from other foreign countries to tax havens “belongs” to those countries rather than the United States. We assume 2 /3 of the excess haven income truly belongs to the United States, since about 2 /3 of U.S. multinational company economic activities are based in the United States. )))

International Coordination

The second pillar of our plan is international coordination. The goal should be a global agreement in which all countries agree to jointly adopt a country-by-country minimum tax. Tax haven countries that have benefited from international tax avoidance are likely to be opposed to this type of cooperation, but many other countries stand to gain. One possibility would be to embed such negotiations in modern, worker-focused trade agreements. Such agreements could begin with a transatlantic effort between the United States and the European Union, or collaboration could focus on OECD or G20 countries, or even the 10 economies that together headquarter about 80% of multinational company profits.(((In 2019 (the year reported in the 2020 Forbes list), only 8% of the Forbes Global 2000 companies are outside of the economies of the OECD, India, China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. The 10 largest headquarter economies together account for 81% of the total profits for these companies. The top ten headquarter economies are (in order) the United States (587 companies), China (266), Japan (217), the United Kingdom (77), Canada (61), South Korea (58), Hong Kong (58), France (57), Germany (51), and India (50).))) One could build on current efforts through the OECD/G20 process, suggesting a simple, comprehensive minimum tax that would address instances of under-taxation for all multinational companies.

Even if an international agreement was initially limited to developed countries, such an agreement would be of great benefit to developing countries. With a sufficiently high minimum country-by country corporate tax rate, developing countries are free to increase their own corporate tax rates without creating incentives for multinationals to move activity, or profits, abroad. Since developing countries lose a particularly high share of their tax bases to profit shifting, a dramatic reduction in profit shifting incentives would be immensely beneficial.

Corporate tax coordination is a key issue for the future of the world economy. For globalization to be sustainable, it is critical to demonstrate that globalization can be reconciled with fair taxation of the winners from globalization. The risk, otherwise, is that more and more voters, falsely convinced that globalization and fairness are incompatible, will fall prey to protectionist and xenophobic politicians, eventually destroying globalization itself. Both trade and immigration have the potential to provide immense benefits to workers throughout the world, but care must be taken to help those that are disrupted by international competition, technological change, market power, and other forces. Adequate corporate taxation can help provide the resources to ensure that those harmed by all sources of economic disruption are made whole.

Defensive Measures and Sanctions Against Tax Havens

Although the ideal solution involves a great deal of international coordination, considerable progress can be achieved by a few leading countries—or even through unilateral action. Indeed, unilateral action can lead to new forms of international cooperation. A striking example is the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA), signed into law by President Obama in 2010, which required foreign financial institutions to report on the foreign assets held by their United States account holders, and which caused many other countries to take similar steps. The automatic sharing of bank information has since become a global standard. A new form of international cooperation, deemed utopian only 15 years ago, swiftly became reality. The OECD recently showed that $11 trillion of offshore accounts came to light in the 100 countries that applied this new exchange of information.(((See OECD, 2020 “International community continues making progress against offshore tax evasion”, online at http://www. oecd.org/tax/transparency/documents/international-community-continues-making-progress-against-offshore-tax-evasion.htm)))

In the context of corporate tax, the United States and other participant countries could impose sanctions on non-cooperative tax havens, perhaps imposing taxes on financial transactions with uncooperative havens, akin to taxes imposed on countries that did not comply with FATCA.

Another possibility would be for the United States to take defensive measures against multinationals incorporated in non-cooperative jurisdictions. The United States could collect a fraction of the tax deficit of multinationals headquartered in uncooperative states amounting to the share of their global sales made in the United States. For instance, for a company incorporated in the Cayman Islands making half of its sales in the United States, the United States would collect half of its global tax deficit. This policy would only increase taxes for companies that pay less than the agreed minimum tax threshold in at least one foreign country. For other companies, nothing would change.

Conclusion

In the end, removing tax competition pressures is a laudable goal for tax systems, but it also serves other important aims. Cooperative collective behavior on tax can buttress goodwill and productive collective action on other fronts, such as climate change and public health. Collective efforts to counter harmful tax competition can further a more equitable globalization, reducing counterproductive backlashes against trade and migration. And, with tax competition set aside, countries can compete based on economic fundamentals that are too often neglected—in part due to fiscal constraints—but make a great deal of difference in residents’ quality of life, such as infrastructure, education, and research.

Polling Methodology

From 7/31/2020 to 8/1/2020, Data for Progress conducted a survey of 1,098 likely voters nationally using web panel respondents. The sample was weighted to be representative of likely voters by age, gender, education, race, and voting history. The survey was conducted in English. The margin of error is +/- 3 percent.