Decades of Federal Policies Turned Local Police On Immigrant Communities. Here’s How Biden Can Stop That.

To make real progress on immigration, the president must address not just four years of bad policy, but the last 40 years.

Introduction

When it comes to immigration, the Biden-Harris promise to “Build Back Better” will begin with the mass demolition of several signature Trump-era policies and the unveiling of new immigration legislation. But it cannot end there. Immigrant communities have already been waiting decades for Congress to act. The Biden administration can and should take immediate executive action to dismantle decades of failed policies that unleashed the tools of mass incarceration—policing, prosecutions, and prisons—on immigrant communities.

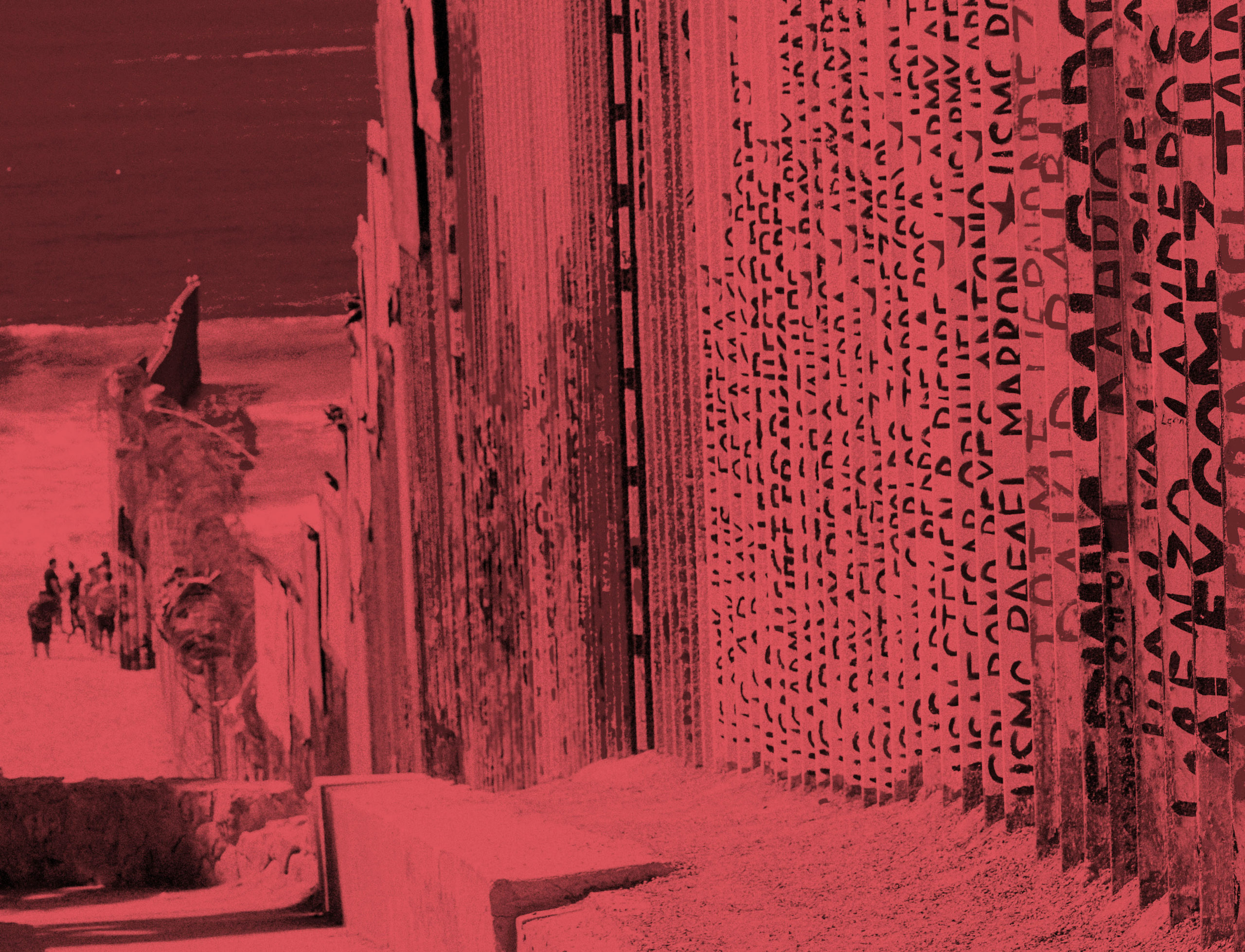

Over the last four years, through more than 400 executive orders, the Trump administration constructed an architecture of cruelty designed to criminalize immigrants of color, redefine citizenship in ethnonationalist terms, and vilify those seeking refuge and opportunity in the United States. It separated families at the U.S.-Mexico border despite knowing that hundreds of children could be forever lost to their families. It banned immigrants to the U.S. from African and majority-Muslim nations under the guise of national security. It repeatedly sought to remove protections for nearly 700,000 people who arrived undocumented in the U.S. as children, and even vowed to end the birthright citizenship guaranteed by the 14th Amendment.

President Joe Biden has pledged to undo these measures and others, which he condemned as “draconian” and “grounded in fear and racism.” But the racism built into our modern immigration system far precedes Trump’s scorched-earth application of it. If the last four years have proven anything, it’s that the groundwork had already been laid for the massive criminalization of immigrants at and within our borders. If Biden is serious about just immigration reform, he will not allow a return to a pre-Trump consensus that leaves intact the machinery of racist enforcement and detention.

Criminalized by Bipartisan Design

Until 1965, racist national origin quotas excluded most immigrants of color from our borders. With the abolition of quotas, immigration restrictionists turned to a new tool to control and punish immigrants: mass incarceration.

By the 1980s and 1990s, Democrats and Republicans alike embraced policies that dangerously entwined immigration with the tools of the carceral state. Programs like the Criminal Alien Program, the 287(g) program, and Secure Communities, among others, amplified the known racial biases of local policing and led to an explosion in the number of people facing detention and deportation with Latinx and Black immigrants facing disparate and discriminatory actions.

The Reagan administration launched the Criminal Alien Program in the late 1980s to facilitate federal immigration enforcement through partnerships with local corrections departments. The program resulted in vast data collection and, in many cases, the physical presence of federal immigration officers in or near jails and prisons. As mass incarceration expanded, so too did the sweep of the Criminal Alien Program, leading to staggering racial disparities without any evidence of improving public safety. A three-year study of the program during the Obama administration showed that more than 90 percent of those deported through the Criminal Alien Program were from Mexico, Honduras, Guatemala, or El Salvador—even though people from those countries make up less than half the noncitizen population in the U.S. Moreover, 80 percent of them had either no conviction or a minor conviction.

The 287(g) program, named after a section of the Immigration and Nationality Act, authorizes the federal government to deputize local police and corrections officers as immigration agents at the request of localities. Although it was enacted under the Clinton administration in 1996, no locality made such a request until 2002. The majority of localities that initially entered into 287(g) agreements shared a common trait, and it wasn’t a higher-than-average crime rate: 87 percent of localities who sought 287(g) agreements experienced a higher-than-average increase in its Latinx population. These agreements allow local police to identify people for deportation through routine encounters such as traffic stops. As a 2011 study demonstrated, roughly half of those targeted through 287(g) were convicted of misdemeanors or traffic offenses. The broad and unchecked powers given to police by this provision encouraged racial profiling, sparking Department of Justice investigations in places like Maricopa County, Arizona and Alamance County, North Carolina.

Then came Secure Communities, a George W. Bush administration pilot program that the Obama administration expanded nationwide. Secure Communities ensures that any fingerprints taken during a local arrest are shared with the Department of Homeland Security, triggering a detainer if ICE suspects the individual is subject to deportation. Like 287(g), the rollout of Secure Communities was strongly correlated with large Latinx communities, and 93 percent of people arrested through the program are Latinx. The majority of those deported through the program were convicted of misdemeanors or traffic offenses, or had no convictions at all.

ICE’s reliance on local policing to identify people for deportation has also had a disparate impact on Black immigrants, who make up 7.4 percent of the noncitizen population but 20 percent of those facing deportation on criminal grounds.

Latinx and Black immigrants are also overrepresented in immigration detention—a sprawling system of mostly private prisons and county jails. The fact that the U.S. government routinely detains immigrants at all in modern times is a vestige of racist policies created to spurn Haitian and Cuban refugees in the 1980s. In the decades prior, as the U.S. Supreme Court observed in 1958, detention was “the exception, not the rule,” and release on parole or bond was the presumption. Today, immigration detention is used at both the border and inside the country. The number of people in detention has exploded over the last four decades, due in large part to mandatory detention policies that categorically deny bond hearings to people with certain types of criminal records. Black immigrants in particular are more likely to face punitive measures in immigration detention like solitary confinement.

These policies were designed to enlist local law enforcement as a “force multiplier” for interior immigration enforcement. In reality, however, they proved only to be a dragnet for deportation—a multiplier of fear and racial injustice.

Justice Through Executive Action

To create a truly just immigration system, the Biden administration must disentangle the criminal legal apparatus from immigration. The promised repeal of Trump’s interior enforcement executive order is a start. As next steps, the Biden administration can and should exercise executive authority to cancel all 287(g) agreements, dismantle the discriminatory Secure Communities and Criminal Alien programs, cancel immigration detention contracts, and release people from immigration custody.

Lesser reforms have been tried and failed. In 2014, for example, the Obama administration attempted to reform Secure Communities, renaming it the Priority Enforcement Program. The Priority Enforcement Program continued to require automatic fingerprint sharing at the front end, while limiting ICE’s authority to issue detainers in some cases. Without ending automatic fingerprint sharing, however, these reforms could not resolve underlying racial disparities. Local policing still placed immigrants on ICE’s radar, inviting future enforcement through raids—including home raids, worksite raids, and raids in sensitive locations like health care facilities, schools, courthouses, and places of worship.

ICE has marketed these types of programs as necessary for public safety. However, studies have concluded that they have had no impact on crime rates. If anything, the entanglement of local policing and federal immigration enforcement has harmed public safety by sowing fear of local police, including among immigrant residents who may be victims or witnesses of crime.

Taking bold executive action to end these programs not only protects immigrants who would otherwise be targeted, but also helps to stabilize families and communities in a country where at least 16.7 million people live in a mixed-status family. For example, a study of 287(g) found that enrollment of Latinx children in public school dropped significantly in localities with these agreements. A study of Secure Communities demonstrated a correlation with lower enrollment in social safety net programs for mixed-status families. Other research shows that Secure Communities has a negative impact on the labor force for immigrant men and women in certain sectors. Detention and deportation generally have destructive psychological and financial impacts on the children, families, and communities of the people detained and/or deported.

Support for bold executive action is evident in successful local and state fights to end involvement in immigration detention and adopt “sanctuary” policies that limit detainers and other forms of collaboration with ICE. These efforts are not limited to more liberal states and localities. Thanks to local organizing, pro-287(g) sheriffs in conservative counties within Arizona, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia have lost re-election. After years of being targeted through these programs, communities of color will not accept the status quo.

Neither should the Biden administration. The time to disentangle federal immigration enforcement from local policing is now.

Conclusion

That Biden has made immigration reform a day-one priority, after President Barack Obama deferred action to his second term, is an overdue change of pace. Some of the measures he introduced would be groundbreaking if enacted. A legislative fix that provides a pathway to citizenship for nearly 11 million undocumented Americans, such as the one proposed on Wednesday, has long eluded Congress.

Still, close attention must be paid to any legislative barriers to citizenship based on contact with the criminal legal system, and Congress should turn to legislative proposals like New Way Forward to provide an inclusive blueprint for immigration reform. Similar vigilance is necessary with respect to any border security measures that threaten human rights. Done right, however, immigration legislation can provide the lasting change that immigrant communities need.

But it is not enough to rely on the legislative process. Obama allowed unjust immigration enforcement to continue within the country while waiting for Congress to act, and the result was a record-breaking number of deportations that still exceeds, year-for-year, that of the Trump administration. The disparity is due largely to Obama’s initial embrace of programs like Secure Communities to identify people to deport.

Biden has promised executive actions—including initiatives to extend Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or the DACA program, and implementing a moratorium on deportations for the first 100 days. Advocates hope that the moratorium will extend past deportation and cover all immigration enforcement, including arrests and detention. These types of actions would provide some relief for millions who live in fear of state violence. It also ensures that people are not detained and deported before they can benefit from potential legislative reforms, which enjoy wide popularity. According to a Pew Research poll conducted last summer, three-quarters of U.S. adults, including 89 percent of Democrats, support a pathway to status for all undocumented immigrants.

As Biden begins to announce his executive actions, communities of color will pay close attention to how inclusive these policies are. Will people who have had contact with the criminal legal system remain targets for draconian immigration enforcement? Will the tools of mass incarceration continue to fuel the deportation machine? The new administration must now decide whether to break the 40-year cycle of criminalization that has turned agents of the state into enforcers of a discriminatory and destructive immigration policy that has sacrificed millions of people of color to detention and deportation.

Alina Das is a professor of clinical law and co-director of the Immigrant Rights Clinic at NYU School of Law.