The Case for Prioritizing COVID-19 Vaccines in Prisons and Jails

By prioritizing incarcerated people and correctional officers in COVID-19 vaccine plans, we will better be able to stem the virus, protect our most vulnerable, and our community at large.

Introduction

Prisons and jails across the country have been breeding grounds for COVID-19. Built to house scores of people in a confined setting, correctional facilities have accounted for a majority of the largest single-site, cluster outbreaks across the country. Nearly 20 percent of the nation’s prison population has tested positive for COVID-19, with an infection rate more than five times higher and an age-adjusted mortality rate three times higher than that of the general population.

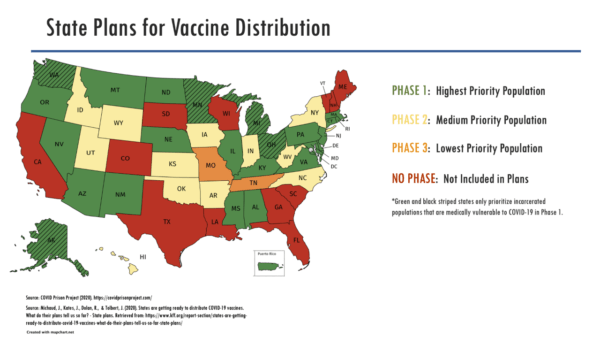

Despite the clear danger to public health, correctional facilities have not always been included in public health pandemic planning and mitigation strategies; the same is true with vaccine distribution plans. Unlike nursing homes and other congregate living facilities, which are also sources of large outbreaks, prisons and jails have not been consistently prioritized for vaccine distribution, even though most of the nation’s prison population is older, has underlying health conditions, and has inadequate access to quality health care. A review of the available vaccination plans for all states and Puerto Rico, conducted by the COVID Prison Project, shows significant variation, with some states prioritizing incarcerated people in phase 1, others vaccinating them in phase 3, and many not explicitly designating them in any phase (See Figure 1). In addition, many jails and prisons have not received the same federal support for vaccine allocation provided to long-term care facilities. This failure of federal backing has forced the distribution burden onto local health departments and the facilities themselves, making large-scale deployment of the vaccine even more difficult.

Fig. 1. Interim plans for vaccine distribution in state prison systems, as of February, 2, 2021

Background

In the first weeks of 2021, the vaccine rollout began in earnest across the country. While there is no national platform or mandate for states to report on vaccine distribution in jail and prison systems, at least 20 states have begun vaccinating incarcerated people as of February 1, according to an analysis of media reports. Vaccine rollout to this population has been slow, with media accounts indicating that even in states that prioritized incarcerated people in phase 1, only a small number of doses have been given. However, mass vaccination campaigns in correctional settings are not only possible, they are effective. In some states where vaccination has begun, initial reports suggest that acceptance rates are high.

But correctional systems urgently require higher levels of vaccine uptake in order to control outbreaks and slow the spread of disease. The transmission dynamics of COVID-19 in correctional environments are associated with higher infectivity, due to facility overcrowding and congregate settings, poor ventilation, high population turnover, and correctional officers who commute daily between the facilities and their homes in the community. Early in the pandemic, in the only study of infectivity in correctional systems to date, our team found a basic reproduction number of 8.44 in a large jail system, meaning that, on average, each person with COVID-19 would infect eight other people, considerably more than estimated for the general population. That figure equates to an estimated herd immunity threshold of 88 percent (based on the equation (1-(1/Ro)). As new, more transmissible variants of COVID-19 continue to emerge, this immunity threshold may be even higher in correctional facilities.

To be sure, competition for a scarce resource creates a number of dilemmas. The vaccine rollout in the U.S. has been slow and logistically complicated, with millions of Americans waiting their turn in line while they worry about their own health. It can be difficult to discuss prioritization of certain groups, especially those who are often stigmatized or considered less worthy. But approaches to vaccine prioritization should not be about perceived “worth”, they must focus on epidemiologic control of illness to protect those who are most vulnerable, as well as the community as a whole. Prioritizing the vaccine for incarcerated populations is thus a straightforward, common-sense public health response.

Recommendations

Vaccinate incarcerated people and correction staff now

We have and continue to recommend the approach from the National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM), which uses the following criteria to justify prioritization of populations at severe risk of COVID-19, taking into account the risk levels of the following:

- acquiring infection

- severe morbidity and mortality

- negative societal impact, and

- transmitting infection to others.

Because incarcerated people and correctional staff rank high in at least three of these criteria, NASEM gave high prioritization to both groups for the vaccine. Prioritizing vaccines for those who live and work in corrections will reduce serious complications from COVID-19 in correctional settings and may also reduce transmission to surrounding communities. The American Medical Association has also affirmed that designating correctional staff and incarcerated people as high-priority populations for the vaccine will protect them and their communities from COVID-19 outbreaks.

Coordination with public health officials is essential for maximizing potential of vaccination efforts

The logistical challenges inherent in vaccine deployment should not dissuade public health and correctional administrators from acknowledging the public health imperative to prioritize incarcerated people and working to achieve this goal.

Both of the vaccines that have concluded phase 3 clinical trials—Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna—require the vaccines to be delivered at recommended low temperatures and as two shots separated by three to four weeks. This poses a challenge for correctional systems with high levels of population turnover. Jails hold people on average for 25 days, often too short a time to administer a second dose of vaccination. Implementation plans will need to account for follow-up shots in the community for individuals who are released prior to receiving the second dose. Historically, this has been done for other infectious diseases that are prevalent in incarcerated populations and can affect community transmission rates, such as hepatitis B, where vaccination is started during incarceration and completed in the community.

However, even if coordination for second doses cannot be confirmed, it is still important to administer the first dose. A randomized trial of the Pfizer-BioNtech vaccine demonstrated that just one dose of the vaccine reduced the relative risk of severe COVID-19 disease by 50 percent The benefit of even one dose of the vaccine is significant enough to merit distribution and prioritization in high-risk settings, like prisons and jails, even if the entire vaccine schedule cannot be completed.

Further, the responsibilities for vaccine distribution and administration should not be left entirely to correction departments or local jails, many of which have staffing shortages and inadequate health services. Public health departments at the state and local level should be working with carceral facilities to ensure prioritization of the population and to develop plans to administer second doses of vaccine after release.

Develop strategies to overcome vaccine hesitancy in carceral settings

Strategies to address vaccine hesitancy and increase vaccine acceptance have not been robustly studied in correctional settings, with a recent systematic review of international prison vaccination rates finding only 28 total studies on vaccination coverage, including just five from the U.S. vaccine coverage rates for influenza vary widely, with rates ranging from less than 10 percent to 70 percent among incarcerated people, and quite low among correctional workers, ranging from 25 to 37 percent. Widespread acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines in correctional facilities may be even more unlikely, especially given the disproportionate incarceration of Black and Latinx individuals. In a national survey of vaccine hesitancy, as of September 2020, just 14 percent of Black adults and 34 percent of Latinx adults reported trusting that a hypothetical COVID-19 vaccine, if offered free of charge, would be safe. Past experience indicates that improving vaccine acceptance requires a multilevel approach, including addressing systems-level barriers to vaccine delivery, individual provider communication, and patient attitudes.

There is an urgent need to develop effective strategies to address COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in correctional systems in order to improve health outcomes in these facilities and in the communities to which people return and in which correctional staff live. The FDA has been working with the Vaccine Confidence Project to increase vaccine uptake, mainly through focus groups with underrepresented communities. The ethos espoused by this group centers on the following tenets: listen, engage, innovate, and co-create. Following this guidance and including incarcerated people, correctional staff, and correctional leadership in planning will ensure more successful deployment of vaccines and increased uptake.

Conclusion

By prioritizing incarcerated people and correctional officers in COVID-19 vaccine plans, we will better be able to stem the virus, protect our most vulnerable, and our community at large. Vaccine priority, distribution, and acceptance is a test of our pragmatism and commitment to fairness. For these reasons, vaccinating people in prisons and jails is an urgent priority.