Why We Need a New Civilian Conservation Corps—And How to Do It

New polling shows that Americans overwhelmingly support the creation of a CCC-like program to tackle today’s economic, social, and environmental crises.

Introduction

The United States currently faces three deepening and converging crises. The first and most obvious is the health crisis produced by COVID-19, which has killed more than 200,000 people nationwide and resulted in acute social isolation for millions of Americans. Second, the state and local lockdowns imposed to stem the virus’ spread have sparked the worst economic slump since the Great Depression. Finally, huge fires across California, Oregon, and Washington state, as well as multiple hurricanes bearing down one after another on the Gulf Coast, all serve as constant reminders that climate change has exacerbated extreme weather events that will only increase in number and severity.

While this convergence of social, economic, and environmental emergencies feels unprecedented, Americans during the 1930s faced a similar triple threat. The Great Depression crippled the stock market, increased the unemployment rate to 25%, and forced 9,000 banks across the country to close. Without work and a steady paycheck, millions of Americans struggled psychologically and physically, often unable to put food on their families’ tables. At the same moment, President Franklin D. Roosevelt became alarmed by several environmental disasters, including flooding along major rivers, extensive deforestation, and, in 1934, the infamous Dust Bowl, which stripped fertile topsoil from farms throughout the Great Plains and blew it as far as the East Coast.

To tackle these crises simultaneously, Roosevelt created several New Deal conservation programs, including the Tennessee Valley Authority, the Soil Conservation Service, and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), which was undoubtedly the most popular of the three. “In creating the Civilian Conservation Corps, we are killing two birds with one stone,” the president explained in one of his early fireside chats. Corps workers would develop state and national parks, manage national forests, plant trees, and prevent and fight wildfires. This work would not only invigorate the national economy, but also conserve the country’s timber and soil while helping to rejuvenate the young men performing such work. As a result, Roosevelt explained, “we are conserving not only our natural resources but also our human resources.”

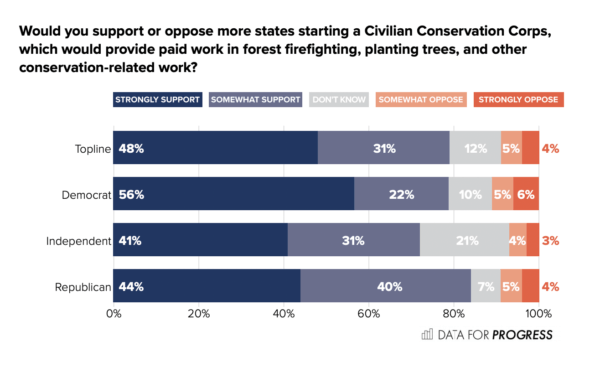

New polling from Data for Progress and The Justice Collaborative Institute shows that Americans overwhelmingly support the creation of a CCC-like program to tackle today’s economic, social, and environmental crises, with 79% of likely voters—including 78% of Democrats and 84% of Republicans—in support:

Would you support or oppose more states starting a Civilian Conservation Corps, which would provide paid work in forest firefighting, planting trees, and other conservation-related work?

Yet for such a program to succeed today, it must build on the original program’s accomplishments while avoiding its pitfalls.

The Successes and Failures of the Original CCC

President Franklin D. Roosevelt established the Civilian Conservation Corps by executive order on April 5, 1933, one month after his inauguration. During its nine-year existence, the CCC provided work to young, unmarried men between the ages of 18 and 25 whose families were on state relief rolls.(((In 1935, the CCC expanded these age restrictions to allow men aged 17-28 to enroll. See Robert Fechner, Summary Report of Director, Fiscal Year 1936 (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1936), 22–23, located at RG 35: CCC, Entry 3: Annual, Special, and Final Reports, NARA.))) These “enrollees” were stationed in approximately 1,400 camps, each housing 200 men, that were overseen by the military and scattered across the country, primarily in state and national parks and forests, as well as on public land in agricultural regions. While the CCC at first undertook mostly forestry work—earning the nickname “Roosevelt’s Tree Army”—it gradually expanded its efforts to include soil conservation, recreational infrastructure development, and a host of other conservation-related projects. Congress halted funding for the CCC in June of 1942, soon after the U.S. entered World War II.

Throughout its existence, the Corps proved enormously successful on the economic, environmental, and social fronts. Financially, the CCC gave jobs to more than 3 million unemployed Americans who earned approximately $700 million (more than $10.5 billion today), the great majority of which was sent back home to each enrollee’s family.(((By law, $25 of each enrollee’s $30 monthly paycheck was mailed back home to each enrollee’s family.))) The program was also an economic boon to local communities, which took in $32 billion (more than $486 billion today) by supplying nearby CCC camps with goods and services.(((According to CCC studies, each Corps camp pumped approximately $5,000 per month back into the local economy through the purchases of goods and services. On monthly expenditures by CCC camps in nearby economies, see Robert Fechner, Third Report of the Director of Emergency Conservation Work: For the Period April 1, 1934 to September 30, 1934, RG 35: CCC, Entry 3: Annual, Special, and Final Reports, NARA, 7.))) The Corps was equally successful in its conservation efforts, planting more than 2 billion trees, slowing soil erosion on 40 million acres of farmland, and creating 800 new state parks while developing dozens of national parks across the country. All told, conservative estimates indicate that CCC work projects altered more than 118 million acres, an area larger than the state of California.(((For these final totals, see James McEntee, Federal Security Agency, Final Report of the Director of the Civilian Conservation Corps, April 1933 through June 30, 1942, RG 35: CCC, Entry 3: Annual, Special, and Final Reports, NARA.))) Last but not least, the Corps’ physical labor helped to restore the physical and psychological health of its enrollees, who on average gained between 11 and 15 pounds while in the CCC. “The actual work, digging, chopping, walking,” explained one CCC enrollee in the mid-1930s, “are splendid means of bodily development and a sound body means a sound mind.”(((Frederick Katz, “How the Civilian Conservation Corps Has Benefitted Me,” Record Group35: CCC, Entry 99: Benefit Letters, 1934-1942, Folder: Misc. Benefit Letters, NARA.)))

Yet the original CCC also made significant missteps. It excluded women and older men, assigned African American enrollees to segregated camps, and placed Native people into a separate program, without residential camps, to perform conservation work on reservations.(((One exception involved hiring what the CCC called “Local Experienced Men,” who were older than the 26-year-old age limit, to train enrollees in forestry skills. Each Corps camp hired approximately 5 LEMs.))) The CCC stumbled environmentally as well, with some ecologically destructive projects such as draining swamps for mosquito control, introducing certain invasive species for soil control, and building roads through wild areas for recreation and fire prevention.(((For a more extended examination of these ecological blunders, see Neil Maher, Nature’s New Deal: The Civilian Conservation Corps and the Roots of the American Environmental Movement (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008), especially chapter 5.))) Even on the economic front there were problems. The great majority of the local communities that benefited financially from nearby Corps camps were in rural areas, where most CCC work took place, and were predominately white. City residents—many of whom were people of color, and who faced a different set of environmental problems involving tainted water, toxic waste, and polluted air— failed to benefit economically or environmentally from nearby Corps camps.

The Solution: A New and Improved CCC

A revived Civilian Conservation Corps must acknowledge and improve on this complicated history. First and foremost, it needs to be more socially inclusive and accept enrollees regardless of gender, age, and marital status, as well as fully integrate its enrollee camps. Doing so is also a matter of economic justice, as today’s unemployment rates for women, older Americans, and Black, Native and nonwhite people remain higher than the national average. A new CCC must also diversify geographically, locating its enrollee camps more equitably throughout the country, to ensure that urban and suburban communities can also benefit financially from having a Corps camp nearby. The work of a revived Corps must be guided by scientific experts, as well, in order to avoid the environmental blunders of the original program, and also account for the local knowledge and needs of residents in communities near CCC camps. Finally, to avoid concerns, prevalent during the 1930s, that the military’s role in overseeing enrollee camps might “militarize” America’s youth, a revived CCC should be administered by a civilian government agency.

An updated CCC should also expand its efforts to tackle a host of new environmental problems that have arisen since the 1930s, many of them in urban neighborhoods. Remediating toxic waste sites, mitigating pollution, and developing urban outdoor recreational spaces and gardens are just a few examples of such projects. Perhaps most importantly, a new CCC should focus on the most pressing environmental problem of our age: climate change. To help communities adapt to the effects of climate change, contemporary enrollees could build climate resilient infrastructure by, for instance, restoring wetlands along rivers and floodplains or by constructing green stormwater management systems that capture more rainfall in urban areas. They could also help mitigate climate change by developing green energy systems, from solar panel installations across the Sunbelt to wind farms in the former Dust Bowl. Today’s enrollees could also do as their forebears did and plant trees to sequester carbon. All of this work would also help train those joining the program for jobs in the emerging green energy sector.(((The original CCC educated its enrollees through on-the-job training during work hours and also through after-work educational classes. On the overall impact of the Corps’ education program on its enrollees, see Maher, Nature’s New Deal, 86-91.)))

Contemporary Examples and Recent Policy Proposals

Recently, federal lawmakers have proposed reviving the national CCC, guided in part by successful state-level programs. In 1976, California Governor Jerry Brown created the California Conservation Corps, which today is the largest and most successful state program modeled on the original CCC.(((Other states besides California that created CCC-like programs in the post-World War II period include New Hampshire, Arizona, Montana, Washington, and Michigan.))) The men and women who enroll in California’s program perform CCC-style conservation work, such as planting trees and halting soil erosion; undertake cutting-edge climate change adaptation and resiliency projects; and respond to natural and human-made disasters, such as the state’s recent spate of devastating fires. The program has also proven effective at protecting enrollees during the coronavirus pandemic, since many of its residential camps are located in remote areas and thus help to isolate the enrollees from more populated locales. Within the camps, however, a sense of community and shared civic engagement is the norm. “It builds on the best part of human beings working together for a greater cause,” Brown recently said of his state’s program. “This is a unifying experience,” he added, one “that’s very important in America today with all the separation and the ideologies that are dividing us.”

On the national level, Illinois Senator Dick Durbin recently submitted the RENEW Conservation Corps Act. The bill proposes putting 1 million unemployed Americans to work on conservation and recreational projects over the next five years. The bill improves on the original CCC in several important respects: All citizens and legal permanent residents over the age of 16 would be eligible to enroll; projects would involve the conservation of natural resources as well the mitigation of climate change; and camps would be located in rural, suburban, and urban communities. Just as important, by ensuring that participants in the new program “reflect the demographics of the area” where projects are being undertaken, the bill encourages local input and community participation. Finally, in exchange for one year of service, all enrollees receive credits they can use towards their postsecondary education.

This bill expands on proposed legislation from Colorado Congressman Joe Neguse, the “21st Century Conservation Corps for Our Health and Our Jobs Act,” which would provide billions of dollars in federal funding to invigorate rural, outdoor economies and support wildfire prevention and preparedness. Like Durbin’s legislation for a new national CCC, this bill would fund job training and hiring for conservation and restoration efforts.

Conclusion

The RENEW Conservation Corps Act would create a new and improved CCC to tackle many of the environmental and social justice crises Americans face today. A revived Corps could implement protocols that would allow it to function during the COVID-19 crisis, would generate jobs to revive the economy, and would undertake the necessary work to fight the effects of climate change. It would also greatly benefit those involved, not only by providing them with a paycheck, credit for their education, and skills for jobs in the private sector, but also with a sense of personal accomplishment, community involvement, and civic purpose.

Polling Methodology

From 9/4/2020 to 9/5/2020 Data for Progress conducted a survey of 1,231 likely voters nationally using web panel respondents. The sample was weighted to be representative of likely voters by age, gender, education, race, and voting history. The survey was conducted in English. The margin of error is +/- 2.6 percentage points.