Voters in Harris County, TX Want Alternatives to Policing, New Approach to Public Safety

Harris County voters want alternatives to policing that enhance public safety and reduce unnecessary encounters with armed police, according to new polling.

Voters in Harris County, TX want to invest in alternatives to policing that are known to enhance public safety while reducing unnecessary encounters with armed police, according to a new poll from Data for Progress and The Lab, a policy vertical of The Appeal. The results show that:

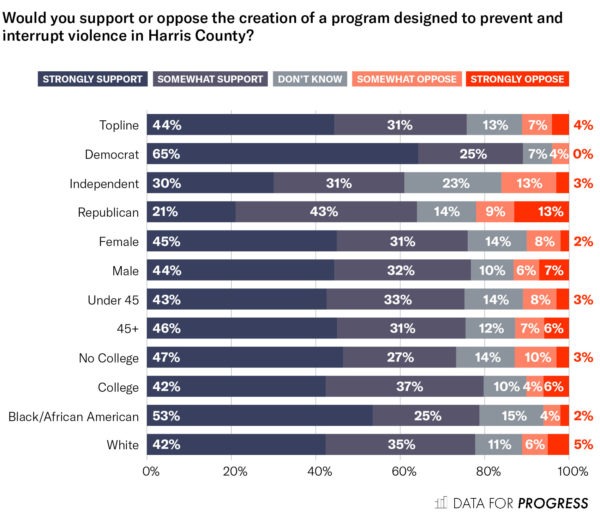

- 75% of voters—including 90% of Democrats, 61% of independents, and 64% of Republicans—support launching a violence interruption program, a preventative approach to gun violence that involves identifying potential conflicts and working with community members to proactively resolve them. Strong majority support for such a community-based program further cut across age, education, gender, and race.

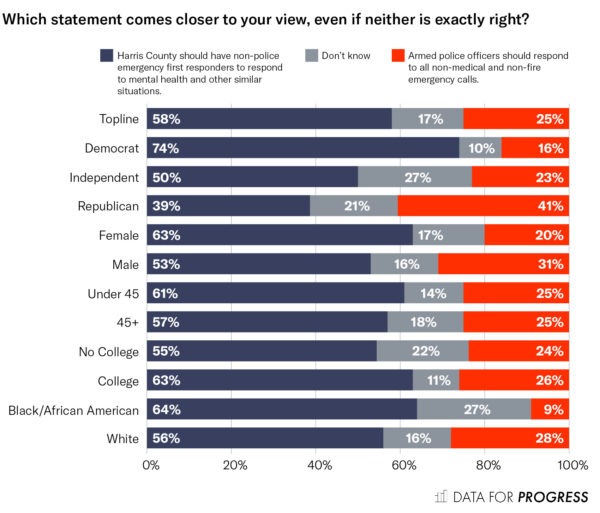

- 58% of voters—including 74% of Democrats and half of independents—agreed that Harris County should have non-police emergency first responders to respond to mental health or substance use crises, or similar situations. By contrast, just 25% of voters would rather have armed police continue to respond to such emergencies.

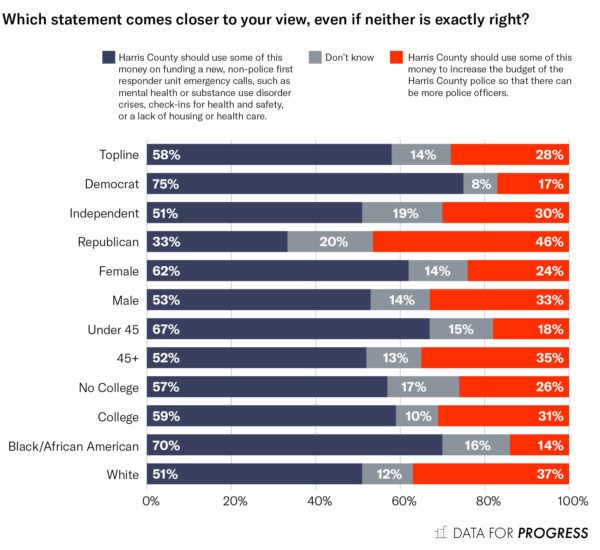

- Asked about the influx of money allocated to state and local governments through the American Rescue Act, 58% of voters—including 75% of Democrats and 51% of independents—agreed that Harris County should use some of those funds to invest in non-police first responders. By contrast, 28% of voters agreed that new federal funding should go to the Harris County police so there can be more police officers.

Programs such as non-law enforcement first response and community violence interruption have grown out of a recognition that armed police are ill-suited to address root causes of crime, and encounters with police too often fuel cycles of violence and insecurity. Harris County is considering implementing both programs.

Poll Results

Many cities and counties have community-based programs designed to interrupt and prevent violence before it happens. By working with communities to identify situations that could turn deadly, interruption can effectively decrease gun violence. Harris County is now considering launching a violence interruption program.

Over the past few years, many cities and counties have changed the way they handle emergency situations that result in 911 calls. In these cities, many emergency calls, such as mental health or substance use disorder crises, check-ins for health and safety, or a lack of housing or health care are now handled by non-police first responders who are experts in addressing mental health and other related issues. These first responders do not carry firearms.

The American Rescue Plan, a recently passed pandemic relief bill, will provide money to state and local governments, some of which Harris County will receive.

Key Context

Across the U.S., elected leaders are grappling with the limitations of addressing complex social problems like homelessness, mental illness, and substance use disorder with the single and often violent tool of policing. For society’s most vulnerable people, encounters with police not only fail yield the support they need, but can also initiate a cycle of harm and result in deadly use of force. According to data from the Washington Post, nearly a quarter of the 6,163 people shot and killed by police since 2015 had a documented mental illness.

In response to this crisis, several cities and counties have adopted alternative public safety models that reduce the intervention of armed police officers. Eugene, Oregon first implemented a non-law enforcement first-responder program—known as Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets (CAHOOTS)—thirty years ago. The program, which has been replicated by other cities and states, involves rerouting some 911 calls to behavioral health clinicians who are trained to address crises involving mental health or homelessness. Last November, San Francisco launched a Street Crisis Response Team (SCRT), which similarly allows behavioral health clinicians and paramedics to respond to certain 911 calls, rather than police officers. Cities like Denver, Los Angeles, and St. Louis, among others, have piloted or implemented similar changes. These programs are broadly popular, backed by nearly 7 in 10 voters nationwide.

Violence interruption programs have also proven effective as a popular alternative to surveillance, arrests, and other policing tactics that fail to prevent shootings and present their own risk of violence. These programs are based on the reality that gun violence is typically concentrated within small social networks, and is often fueled by cycles of conflict and retaliation. Interruption programs enlist the help of outreach workers from communities to provide peer-based mentorship, and also may involve job training and other social supports to disrupt cycles of violence. Studies have shown that mistrust between law enforcement and communities exacerbates gun violence, and that communities are often more effective than police at addressing the problem.

In Harris County, efforts to study the viability of such programs have been approved by the County Commissioner’s Court, with the implementation of pilot programs in progress. County officials are assessing which 911 calls might be routed to behavioral health first responders, as opposed to police officers, and which public health techniques might be incorporated into new community-based programs to interrupt violence independent of law enforcement.

While some municipalities have financed such programs through cuts to their police budgets, advocates have pointed to the massive influx of federal coronavirus relief funds as another opportunity to fund better public health and safety systems. Harris County and Houston are expected to receive $900 million and $615 million, respectively, from the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan, which President Biden signed into law on March 11. According to local officials, half of the money will be available in 2021, with the remaining half available in 2022.

Polling Methodology

From March 19 to March 26, 2021, Data for Progress conducted a survey of 466 likely voters in Texas using web panel respondents. The sample was weighted to be representative of likely voters by age, gender, education, race, and voting history. The survey was conducted in English. The margin of error is ±5 percentage points.