Poll: Marylanders Support Removing Governor’s Veto Over Parole Decisions

A new statewide poll shows that Marylanders support removing the governor from the parole process.

Maryland is one of only three states—along with California and Oklahoma—in which the governor has the final authority to accept or reject parole recommendations, an effective veto power that politicizes an otherwise thorough, deliberative process. For decades, governors of both parties have turned their backs on people recommended for release, all but abolishing parole for people serving life sentences. As a result, people who have demonstrated rehabilitation and who could safely return to their families and communities have needlessly languished in prison, in some cases for decades.

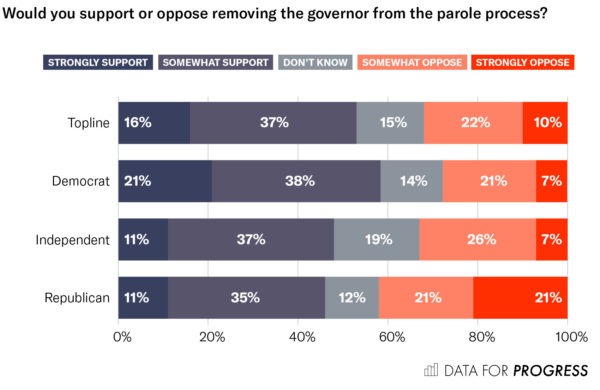

But as the state legislature advances a reform bill that would eliminate the need for governor approval, a new statewide poll from Data for Progress and The Lab, a policy vertical of The Appeal, shows that Marylanders support change: 53 percent of likely voters support removing the governor from the parole process, while only 32 percent oppose—a difference of 21 percentage points in favor of bringing Maryland’s parole process in line with the vast majority of other states.

The state House of Delegates passed the reform bill on March 4 with a 93-41 vote. The state Senate must also approve it before it goes to the governor’s desk.

Poll Results

Some in Maryland are proposing removing the governor from the parole process. Maryland is currently one of only three states where the governor has to approve parole recommendations.

Supporters of this policy say that the governor undermines the purpose of parole by unfairly adding politics to decisions that should be about promoting rehabilitation and public safety based on the individual facts and evidence in each case.

Opponents of ending this practice say that the governor provides important political accountability before people with violent records are released.

Key Context

Nearly 2,100 people in Maryland are serving parole-eligible life sentences, including about 340 people sentenced for crimes committed before the age of 18, and about 400 people who are age 60 or older.

Under state law, they all should have a meaningful chance for release—an opportunity that provides crucial hope for people otherwise sentenced to die in prison, and creates an incentive for people to pursue work, education, and treatment, and to stay connected with the communities to which they may someday return.

Before someone’s name even gets to the governor’s desk, the state’s 10-member Parole Commission conducts an exacting review process that includes risk assessments, in-person interviews, and medical and psychological evaluations. Only a tiny fraction of people serving parole-eligible terms earn the Board’s approval. Those that do must then be approved by the governor within 180 days (under a 2011 law, parole is also approved if the governor takes no action), a final step that, in practice, has virtually eliminated the possibility of parole.

In 1995, then-Governor Parris N. Glendening announced that “life means life” and that he would never grant parole for someone serving a life sentence, no matter what they did to earn it. He kept his promise. His successor, Bob Ehrlich, a Republican, likewise turned down every parole recommendation (although Governor Ehrlich did release five people serving life terms via commutation, including people whom the Commission previously endorsed for parole), as did Democrat Martin O’Malley, who succeeded Ehrlich in 2007 and served until 2015. Current Governor Larry Hogan, a Republican, has loosened the effective ban on parole, but only slightly. In November 2019, the Washington Post reported that Hogan had overruled the Parole Commission’s recommendation for release for all but three of 21 people who had been sentenced to life sentences as children. Overall, Hogan has granted release for just 29 people despite the Commission recommending parole in well over 100 cases.

Last week, former Governor Glendening wrote an op-ed admitting that he had been “completely wrong” to summarily foreclose the possibility of parole, and that his decision had been driven by politics, not evidence or public safety. “How can it not be political,” he wrote, “for a governor to hold all the power in the decision about whether to release someone who has been involved in a serious crime?”

Polling Methodology

From February 26 to March 2, 2021, Data for Progress conducted a survey of 669 likely voters in Maryland using web panel respondents. The sample was weighted to be representative of likely voters by age, gender, education, race, and voting history. The survey was conducted in English. The margin of error is ±4 percentage points.

CLARIFICATION: This piece has been updated to reflect that former Maryland Governor Bob Ehrlich used the clemency power to commute the sentences of five people serving life terms for murder, including people whom the Parole Commission previously endorsed for release on parole.