Rep. Rashida Tlaib: The Case For An Emergency Responder Corps

As the coronavirus crisis continues to expand, it is clear that America needs a robust assistance program for the most vulnerable, such as the elderly and physically disabled, to ensure they have what they need to survive. The health, safety, and stability of all communities depend on it. This research and analysis is part of […]

As the coronavirus crisis continues to expand, it is clear that America needs a robust assistance program for the most vulnerable, such as the elderly and physically disabled, to ensure they have what they need to survive. The health, safety, and stability of all communities depend on it.

This research and analysis is part of our Discourse series. Discourse is a collaboration between The Appeal, The Justice Collaborative Institute, and Data For Progress. Its mission is to provide expert commentary and rigorous, pragmatic research especially for public officials, reporters, advocates, and scholars. The Appeal and The Justice Collaborative Institute are editorially independent projects of The Justice Collaborative.

The current public health crisis and national emergency caused by COVID-19 in our country has shed light on just how broken our current systems are for people in distress. Like all large-scale changes, the people who were the most vulnerable in society before the pandemic are now its most likely victims – the elderly, folks who are mentally ill, people experiencing homelessness, the working class, people of color and people with disabilities. Here in Michigan, for instance, Black people make up 14 percent of the state’s population, they account for 33 percent of COVID-19 cases and a staggering 40 percent of deaths.

Congress has already authorized some payments to citizens, but the benefits are not bold or aggressive enough. This $2 trillion stimulus package provides for one-time cash payments. This acknowledges that people need cash in their pockets to survive, but alone, it falls short.

We need to do more and with a sense of urgency that still seems lacking in policy making. There should be more cash benefits throughout the next year and beyond, enough to help people get back on their feet — like those proposed by my Automatic BOOST to Communities (ABC) Act. The benefits need to be automatically distributed and easily accessible through a debit card. Too many of our neighbors are unbanked and underbanked.

But we have to go even further. We need a government that reaches out to the most vulnerable and ensure they have what they need. These are our neighbors without internet access or cell phones, or hard to reach places. I’ve been all over my district — the third poorest in the country — and know that many of my families are struggling to access the information they need to survive.

Throughout the crisis, it has been inspiring to see the number of people willing to put themselves in harm’s way to protect their neighbors. There are the health workers and hospital staff working through the night to save lives. There are small local collectives of people who want to do more. They are delivering groceries to those who are most at risk of contracting COVID-19, the elderly and the sick. They are checking on each other and asking, “What do you need?”

There is only one inescapable fact — we must be together even in the moments where we must stay apart. Too often, people in need of help get a list of phone numbers. They pay the toll when government fails them.

We need transformative approach that is focused on saving lives. I’m proposing the Emergency First Responders Corps, which will perform affirmative outreach, knocking on every door, using mobile resource stations, and actively striving to reach people who are the most vulnerable. The woman on disability who can’t leave her apartment because there is no elevator. The working mother with young children who doesn’t have time in her day to go to government offices during work hours. The recent immigrant concerned about whether accessing resources will put their family in jeopardy. The veteran who was diagnosed with mental illness, lost his home, and cannot get his prescription filled.

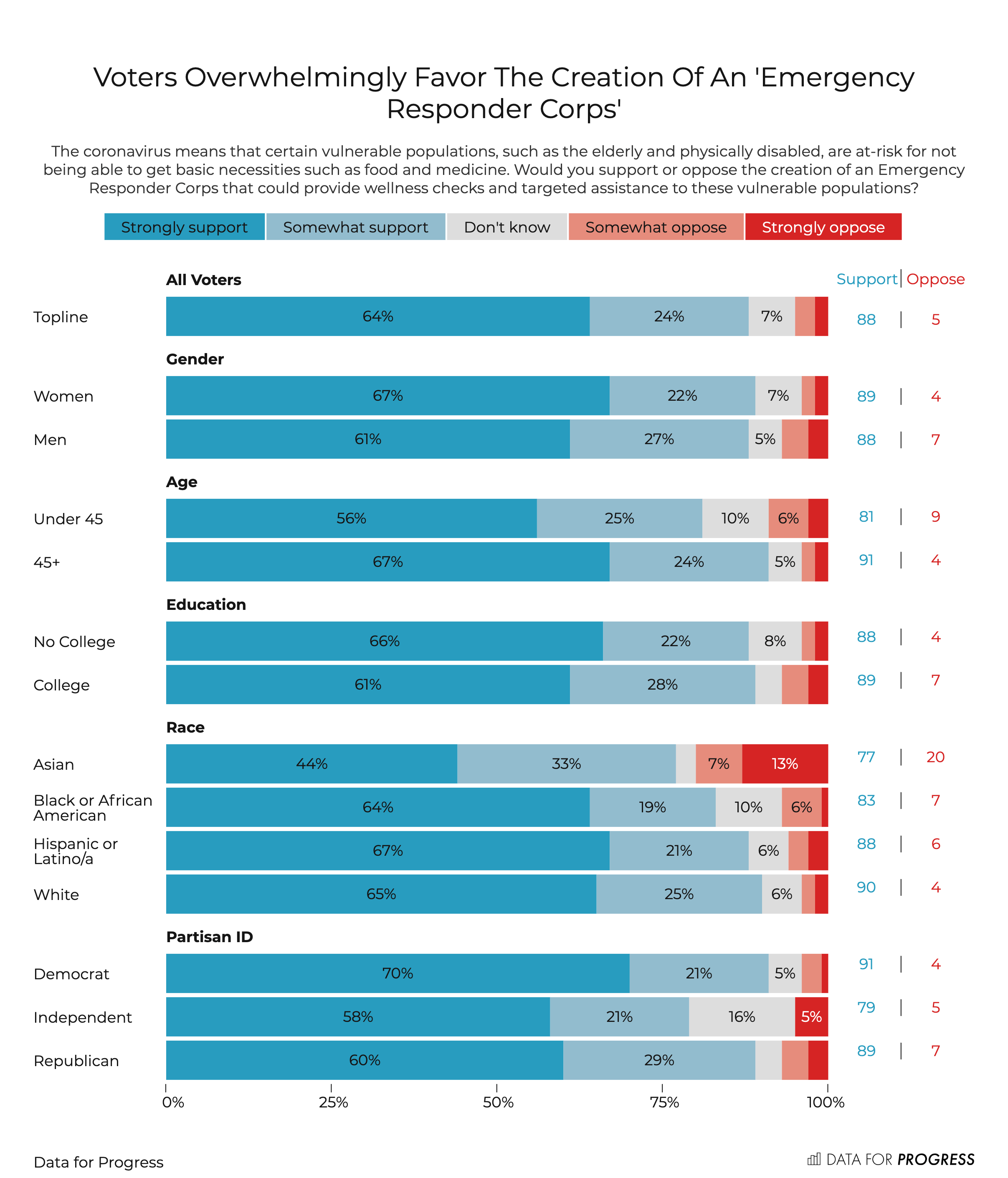

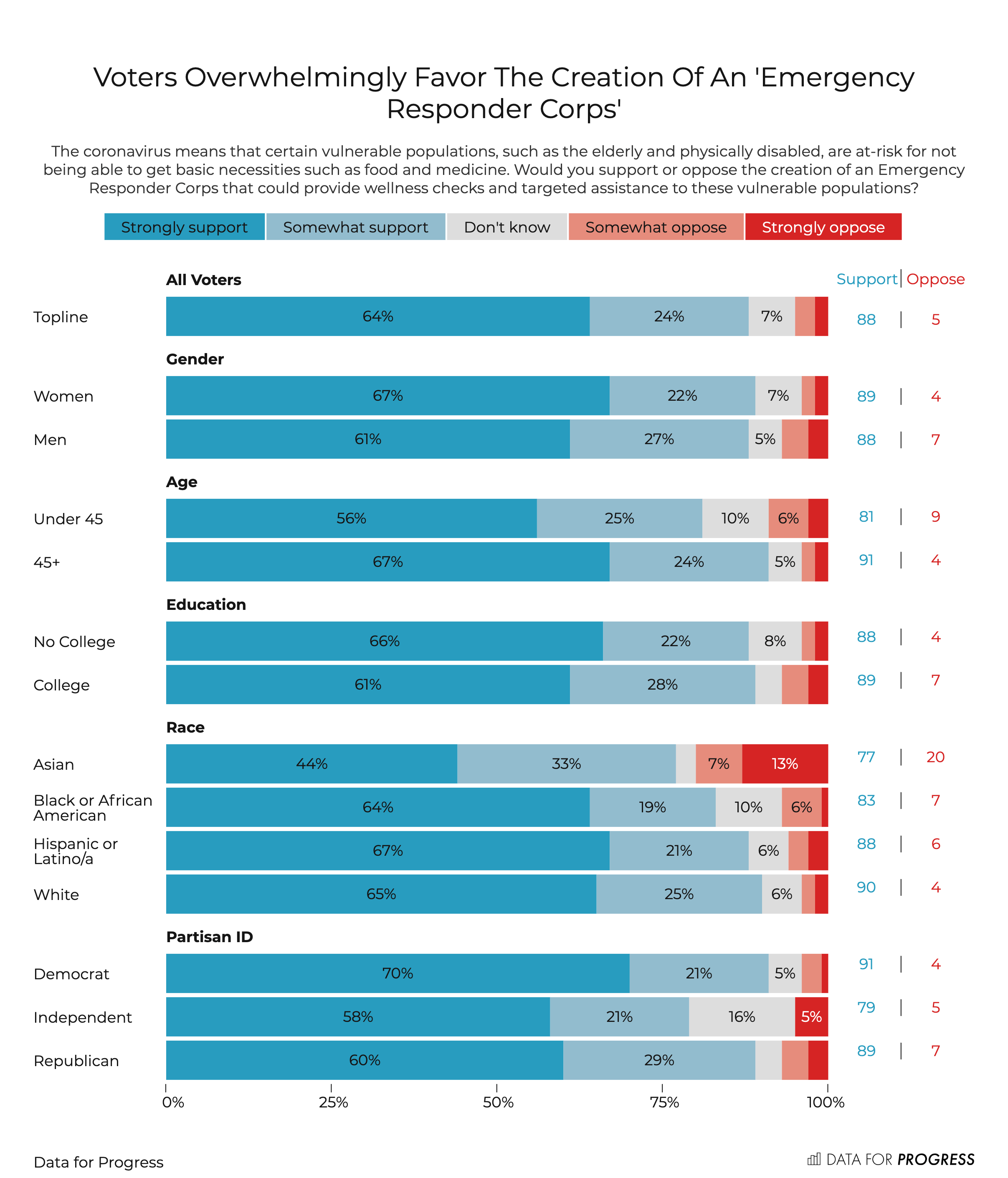

New polling from The Justice Collaborative Institute and Data for Progress has found that an overwhelming percent of respondents — 88 percent — supported the creation of an Emergency First Responder Corps to conduct wellness checks and assist the elderly and disabled. This isn’t a surprise. People understand that communities need each other, and this has only become more obvious in a time of crisis.

The ABC Act is intended to give people across the country stability, reliability of income and housing, and information about available resources. Modeled on the community outreach and neighborly assistance people have been doing for centuries, an Emergency First Responder Corps will ensure that the provisions in the ABC Act actually reach the people they are intended to help.

Why an Emergency First Responder Corps?

The Emergency First Responder Corps is an important way to ensure that everyone can access government benefits, like those in the ABC Act, which give prepaid debit cards to everyone, regardless of income tax filing status. The only way to ensure all of these benefits reach the most vulnerable people is to have real live humans who can specifically target assistance for those most in need.

The most important part of the ABC Act includes debit cards which contain money people can use to pay bills, rent, and food. The Emergency First Responders Corps will make sure that the pre-loaded debit cards get to isolated people and those who are so medically vulnerable they cannot leave their homes.

Members of the Emergency First Responders Corps will also ensure that people have access to the full array of available assistance. This is about providing a foundation of stability for everyone; stabilizing people economically and providing additional one-on-one assistance for the most vulnerable.

And, as COVID-19 has revealed just how difficult it is for many people to access traditional health care, the Emergency First Responders Corp will also bring health care resources. According to a 2016 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report, about 17 percent of patients don’t have a regular place to access health care. Until there’s universal health care, the current system leaves out a lot of people: those of color, immigrants, the uninsured, the unemployed, the elderly, and those with disabilities. We need proactive solutions that meet people where they are, not ones that force people to face a dangerous virus by waiting in crowded emergency rooms.

Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic is not just a health crisis — it’s also revealing just how vulnerable some people really are. Among the elderly, for example, the New York Times found that a vast majority 1 in 4 elderly Americans’ greatest fear is dying alone. Because of the nature of a viral pandemic, the sick and vulnerable are isolated, treated by masked doctors, and separated from friends and family. There are good health reasons for this, of course. But it’s also terrifying and heartbreaking.

COVID-19, in particular, strikes the elderly and those who live in crowded conditions, like nursing homes, which makes it particularly dangerous for people who need help. For example, the New York Times described how COVID-19 has run rampant through homes for the disabled, who live in group settings like the elderly and are unable to even communicate their symptoms. In Detroit, nursing homes are struggling to keep up as cases spread and claim lives at staggering rates.

Under current stay-at-home orders, it’s extremely difficult for many people to access basic needs. Some public health experts argue that even the minimal contact required for getting basic necessities puts people in danger. Anyone who’s tried to order groceries knows that either delivery is unavailable or unaffordable, especially for the people who are most vulnerable. While some people are able to rely on family members or neighbors, there are many who are alone. In fact, they may be so isolated that they don’t have information about COVID-19, an understanding of available resources, nor even a number to call.

What would an Emergency First Responders Corps look like?

The most important aspect of the Emergency First Responder Corps is that it must be civilian and designed to help people. The idea isn’t novel — it is something neighbors have been doing for centuries, and the time is now to take comprehensive approach to formalizing it to help our most vulnerable communities.

A good model of this exists in Eugene, Oregon, CAHOOTS — Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets — has worked for decades to help people in crisis. They deal with those who are suicidal, houseless, infirm, or just having trouble getting the basics they need to survive. It’s fully integrated into the local service community. And they are effective. In 2018, CAHOOTS responded to 24,000 calls. CAHOOTS and the White Bird Clinic were recently awarded federal funding to expand telemedicine access during the current pandemic.

An Emergency First Responders Corps can also provide additional services that close the gap for the working poor, people who don’t qualify for some programs but who need assistance with housing or health needs. We must fund programs that provide on-the-spot services and help people sign up for additional benefits. This gives busy families a link to service without waiting in the lobbies of a government office or clogging the phone lines of an overtaxed state hotline.

One of the most important aspects of any outreach is a complete severance from law enforcement and the fines, fees and incarceration that follows. Decades of pouring money into cops, jails, and prisons has left the criminal legal system as the only option in many places. But, we know that law enforcement members are not properly trained to conduct welfare checks. The results are often ineffectual and sometimes deadly. Almost half of all police encounters ending in a civilian death involve someone in a mental health crisis.

An Emergency First Responders Corps would sever that link between police and interactions that are primarily health-related. Alternatives that include trained behavioral health experts could dramatically reduce incidences of violence, reduce arrests, and minimize dangerous interactions between law enforcement and people whose problems are best treated with non-jail solutions. By diverting money that would otherwise go to the bloated system of mass incarceration, federal and local governments could instead fund a first response program solely dedicated to the distribution of resources and assisting the most vulnerable. This would have long-term safety benefits for the community.

Americans support an Emergency First Responders Corps

Polling shows that nearly all respondents (88 percent) supported the formation of an Emergency First Responders Corps that would conduct wellness checks and assist the elderly and disabled. Support remained high for all categories.

- 89% of respondents who identified as Republican supported or somewhat supported the idea.

- 91% of respondents who identified as Democrats supported or somewhat supported the idea.

The worldwide emergency created by COVID-19 has shown most people just how fragile life can be. Many of us can remain housed, fed, and healthy through the help of support groups. But, the nature of modern society means that some people are left out. Among them are those most vulnerable to COVID-19, the elderly and disabled.

Providing assistance to those who cannot help themselves has near universal support. It’s not surprising to hear that — I see examples of this love and solidarity in my community all the time. While lawmakers and governors may suggest that we should sacrifice our grandparents to re-open the economy, that’s not what people want. Communities know that everyone is stronger when we stand together.

From March 27, 2020 to March 28, 2020, Data for Progress conducted a survey of 2022 likely voters nationally using web panel respondents. The sample was weighted to be representative of likely voters by age, gender, education, urbanicity, race, and voting history. The survey was conducted in English. The margin of error is ± 2.1 percent.

U.S. Congresswoman Rashida Tlaib represents the 13th District of Michigan.