Mother Of Slain 4-Year-Old Says Pennsylvania Should Release Death Row Prisoner With COVID-19 Symptoms

Sharon Fahy, whose daughter was murdered in 1988, asked the court to release Walter Ogrod, the man convicted in her killing.

Sharon Fahy, whose daughter was murdered in 1988, asked the court to release Walter Ogrod, the man convicted in her killing.

People are dying in jails and prisons because elected officials hesitated at the worst possible moment.

Michigan was one of several states requiring registrants to report to local police stations in person despite the risk to public health from coronavirus.

Louisville, Kentucky judges are ordering people with COVID-19 who have allegedly defied quarantine to wear GPS ankle monitors, raising ethical questions about the government’s role in a pandemic.

Twenty-eight people were to attend weeks-long drug treatment programs after violating parole. The COVID-19 pandemic nearly trapped them in jail indefinitely.

On the intersection of two public health crises: housing and COVID-19.

Public defenders are working with the courts to secure release for people incarcerated in the Florida county, many of whom are jailed for low-level offenses.

They make roughly half the average national income, and they’re at risk of COVID-19 exposure as they continue to work to ensure shelves are restocked and communities fed.

Experts are urging large-scale releases. But the Department of Justice often operates contrary to expertise.

‘They’re not supplying us with masks, they’re not supplying us gloves, they’re not supplying us with decent cleaning supplies.’

Despite risks to incarcerated people and the public, Florida is sending prisoners to perform hard labor.

‘We literally held an election during a pandemic.’

In Alabama and elsewhere, canceled hearings and new procedures are complicating the parole process for people hoping to be freed.

It took a prisoner’s death ‘just for them to pass out a single extra bar of soap,’ one incarcerated man said.

As infections and deaths mount, state leaders and law enforcement are turning to tough-on-crime tactics in the face of the COVID-19 outbreak.

In Austin and across the country, service providers are dealing with spikes in demand, new logistical challenges, and mounting uncertainty about the months ahead.

Bail will be set at $0 for most misdemeanors and low-level felony offenses.

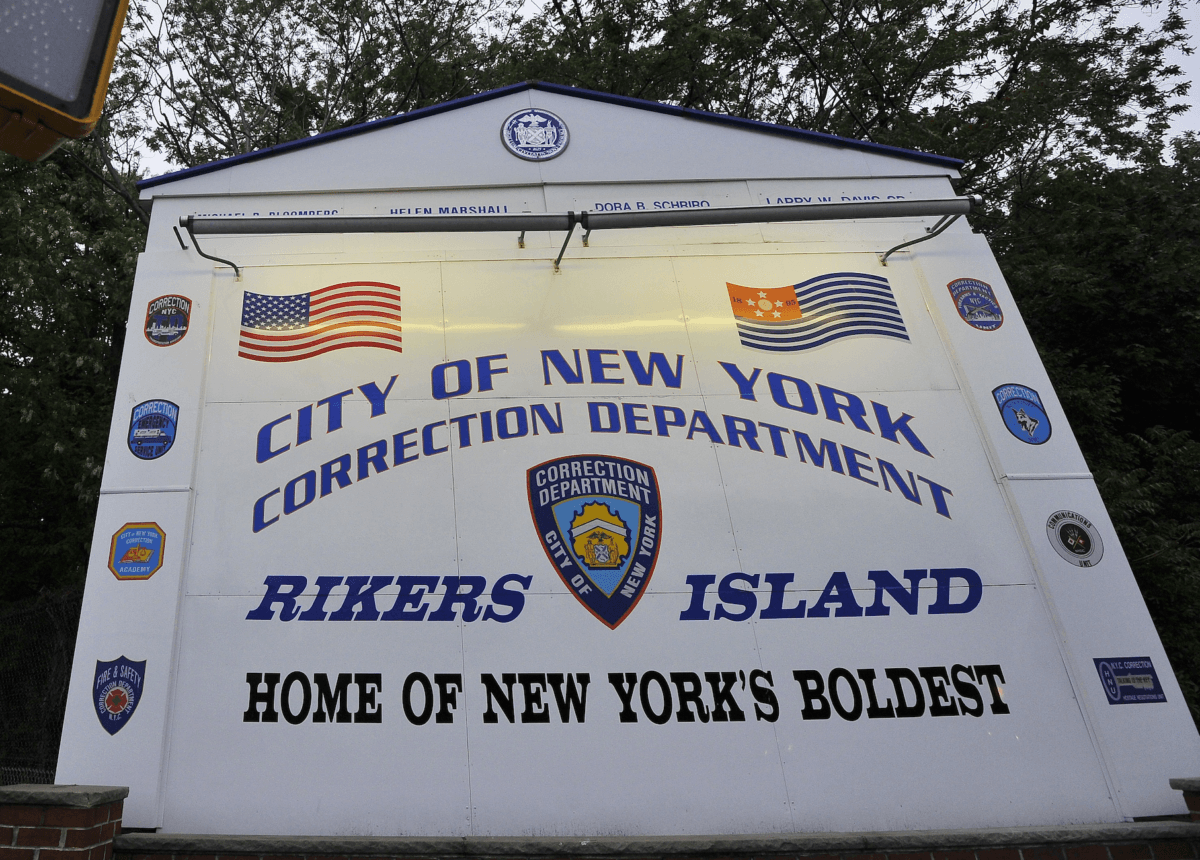

The state, which accounts for roughly one-third of all positive COVID-19 cases in the country, is facing a rapid spread of the disease in its jail and prison systems.

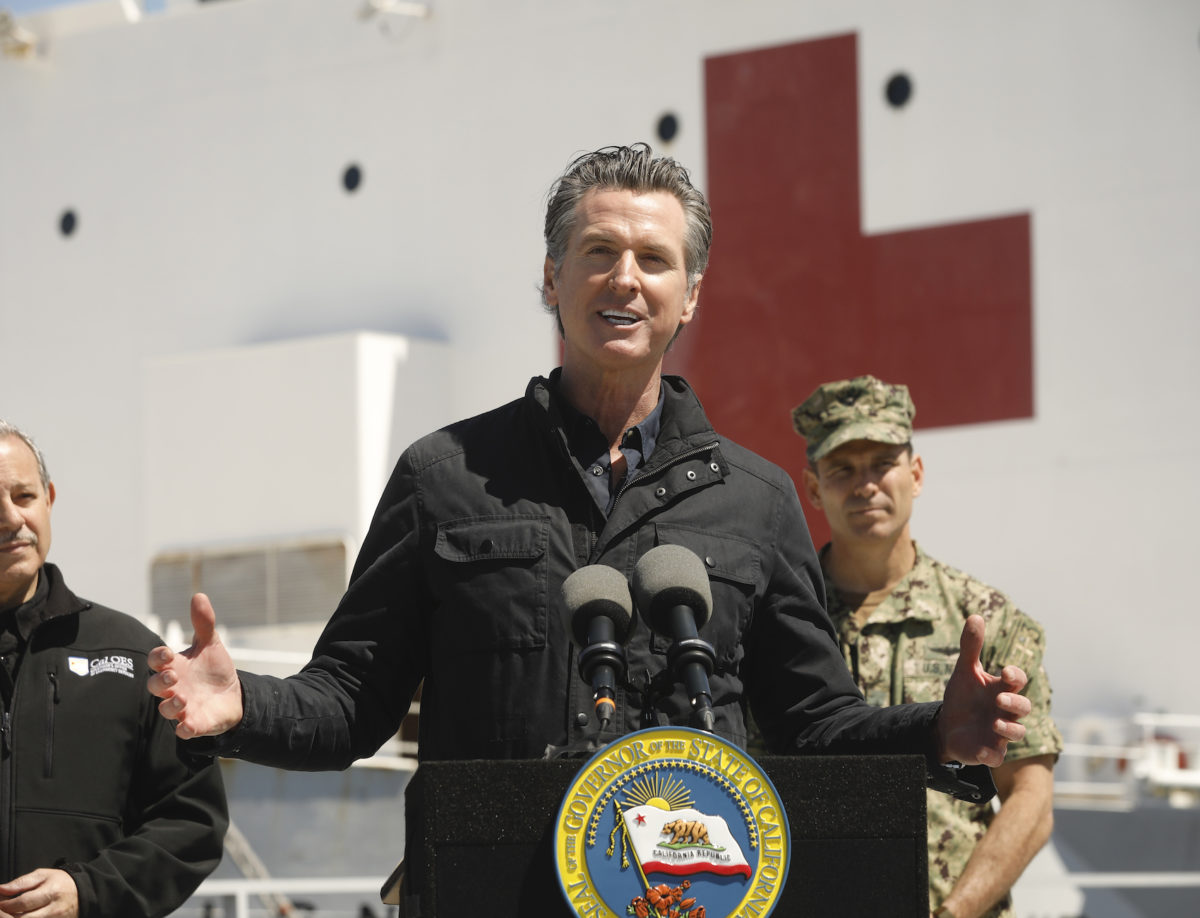

The emergency program seeks to release a select group of prisoners but does not go far enough to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in prisons, experts and Democratic lawmakers say.

Incarcerated people, corrections officers, and their families and communities are bound together by the threat of a deadly and fast-moving disease. The sooner we recognize this, and take decisive action, the more lives we will save.

Lawyers, judges, and advocates for migrant children wonder what it will take to close all 69 immigration courts. ‘I hope that it won’t take a death, but I worry that it will,’ one lawyer said.

Inconsistent rules nationwide mean some people are still registering and reporting in person despite public health directives meant to control COVID-19.

Men in Unit B-2 at the Shawangunk Correctional Facility say staff members have harassed and abused them since they possibly came into contact with an infected officer.

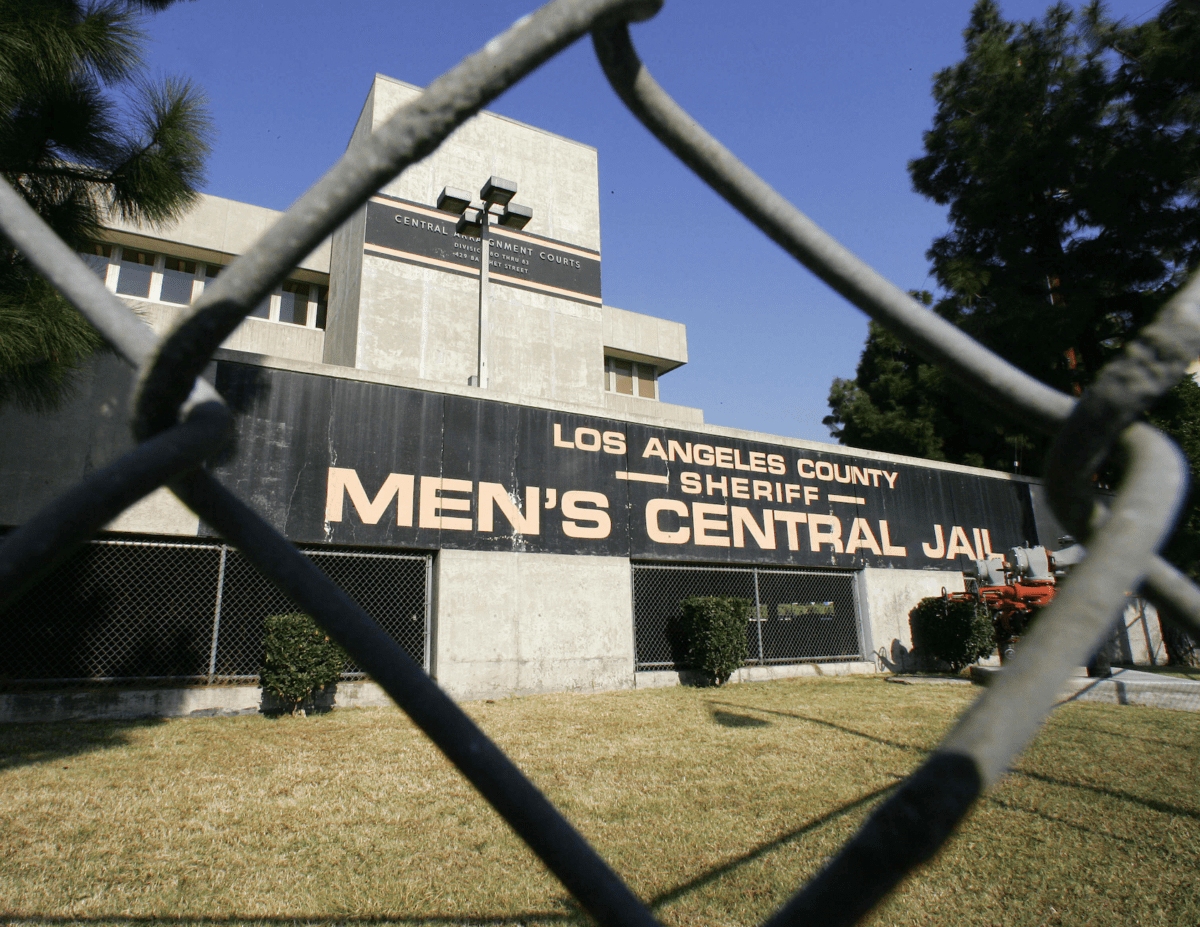

Los Angeles County judges must move quickly to release a broad group of people in custody.

Telecommunications companies that serve prisons and jails, like Securus Technologies and Global Tel Link, are offering a limited number of free calls, but families say it’s not enough.

Conservative lawmakers are using emergency measures to restrict access to care.

As the novel coronavirus spread in the state, a Solano County judge denied numerous motions to continue a troubled double kidnapping and rape case marred by allegations that a Vallejo police detective withheld exculpatory evidence.

Public defenders in Fairfax County say their clients are being sent into harm’s way.

Delaying trials will mean more people stay in jail while a life-threatening disease spreads throughout the state.

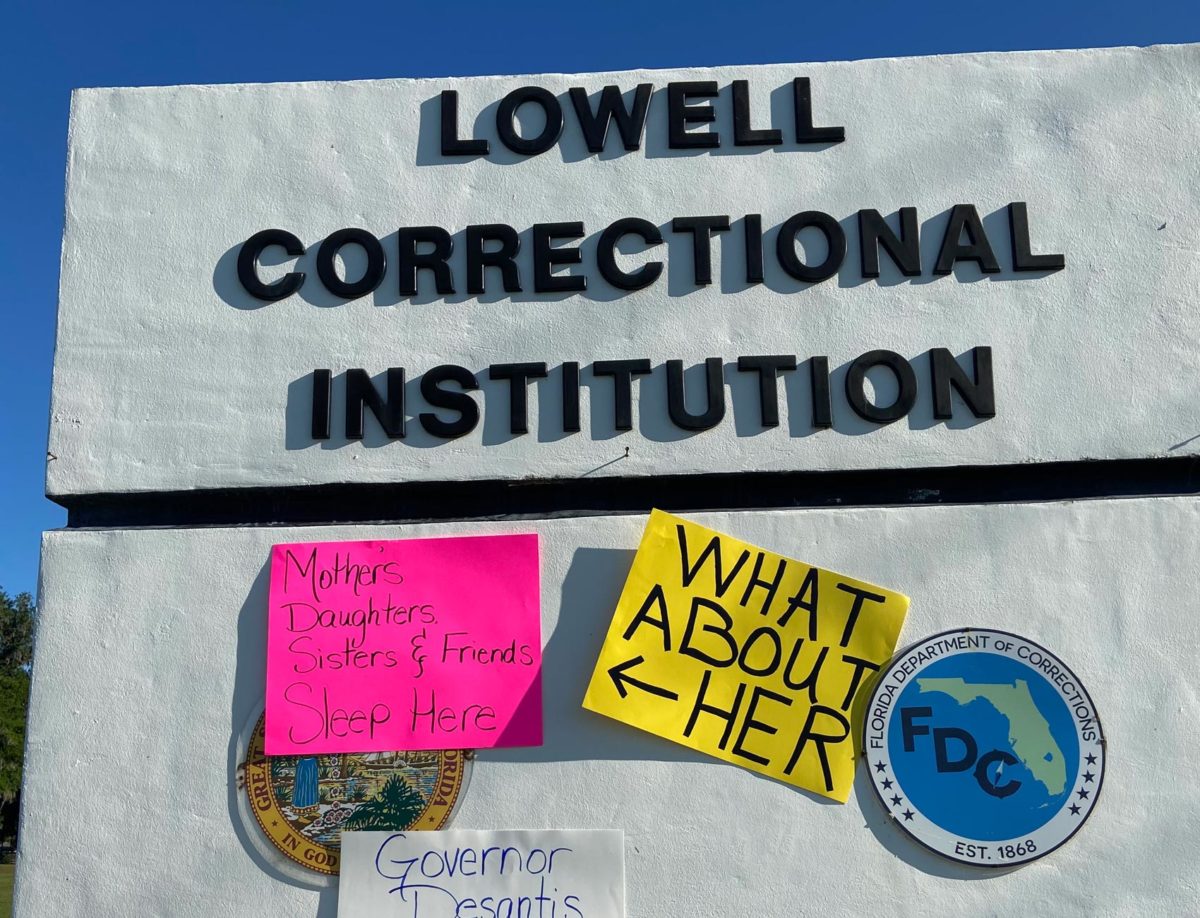

With COVID-19 rapidly spreading across the state, there’s heightened concern that the conditions inside Lowell Correctional Institution, coupled with the prison’s sizable elderly and pregnant population, could foster a deadly outbreak.

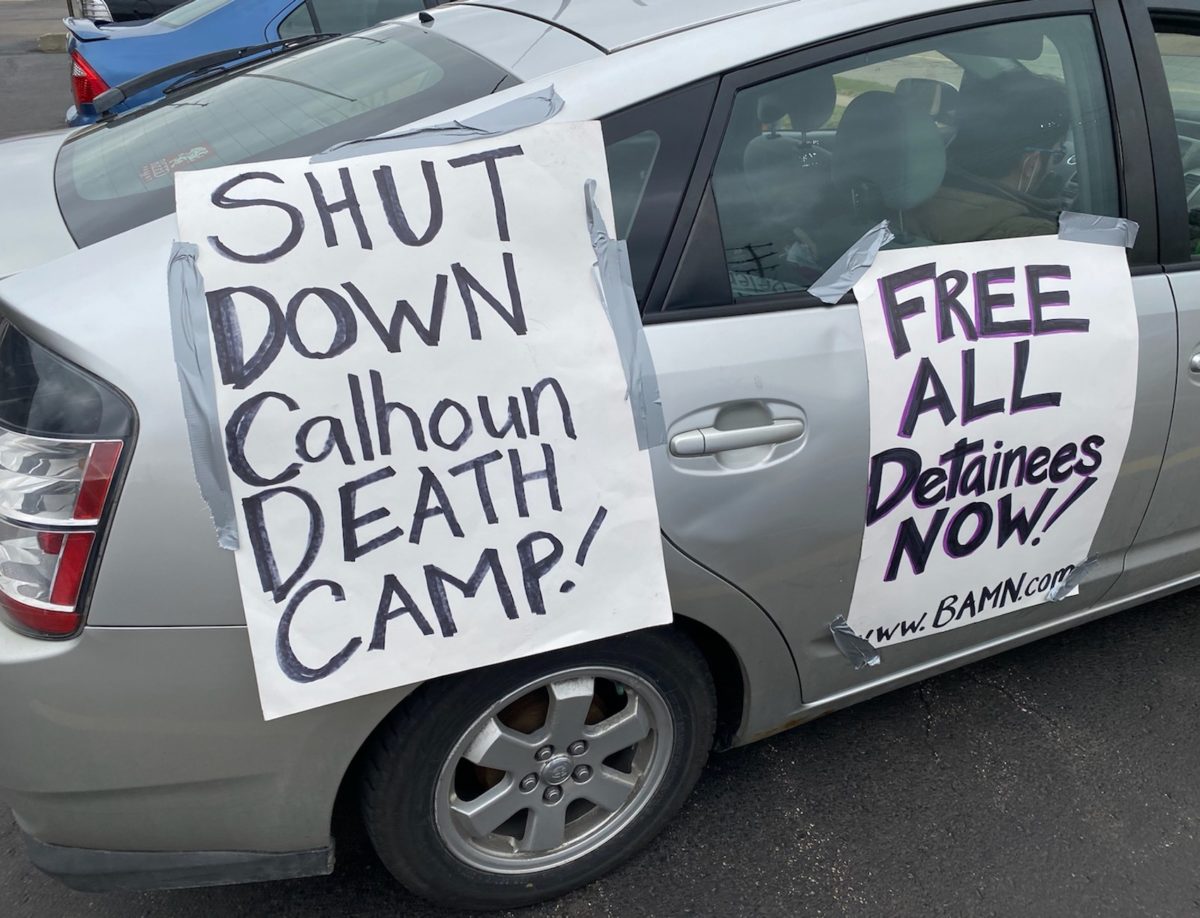

ICE has adopted no policies aimed at releasing any of the 38,000 people it keeps in county jails and private detention centers across the country.

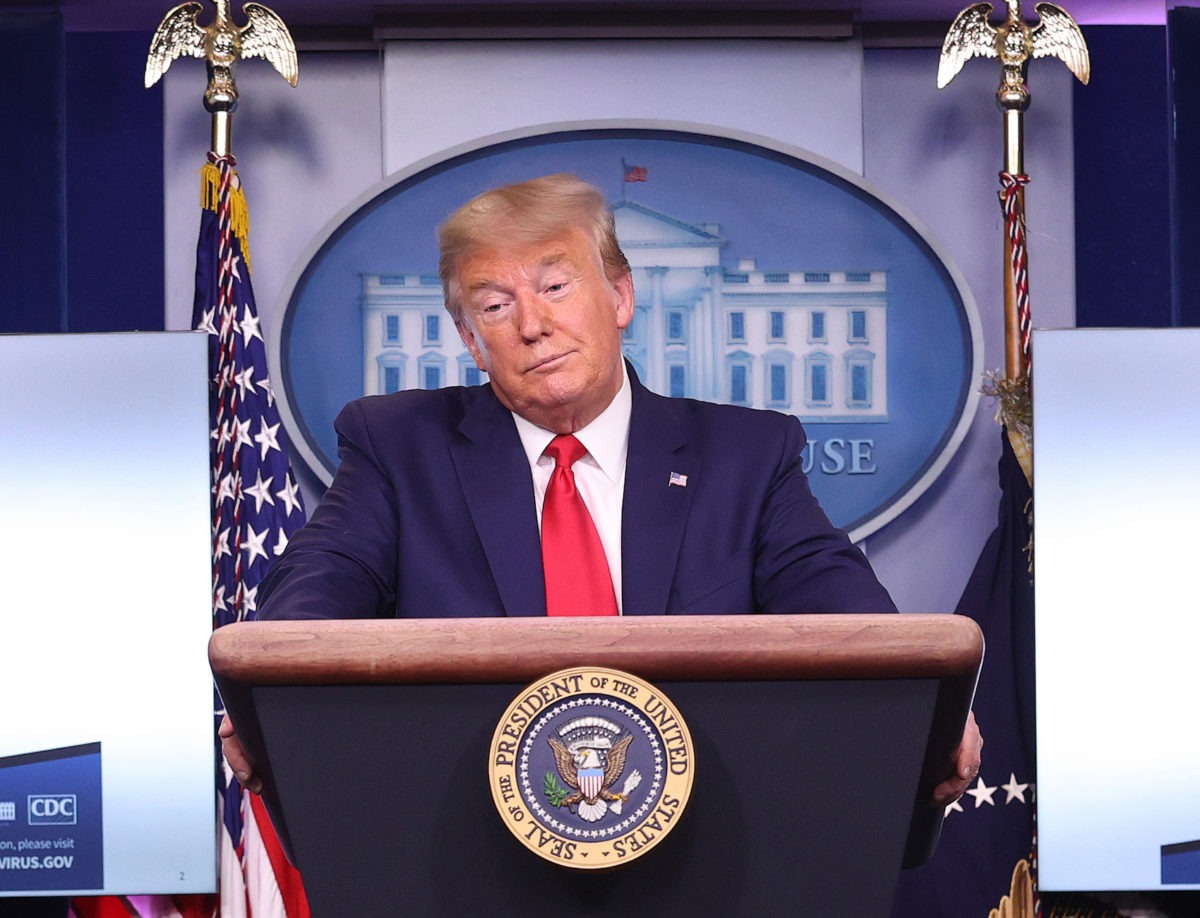

There are no good reasons for the president to keep vulnerable people behind bars any longer.

Residents have been told to stay in their homes to slow the spread of the novel coronavirus—but little has been done to ensure they can afford to stay there, activists say.

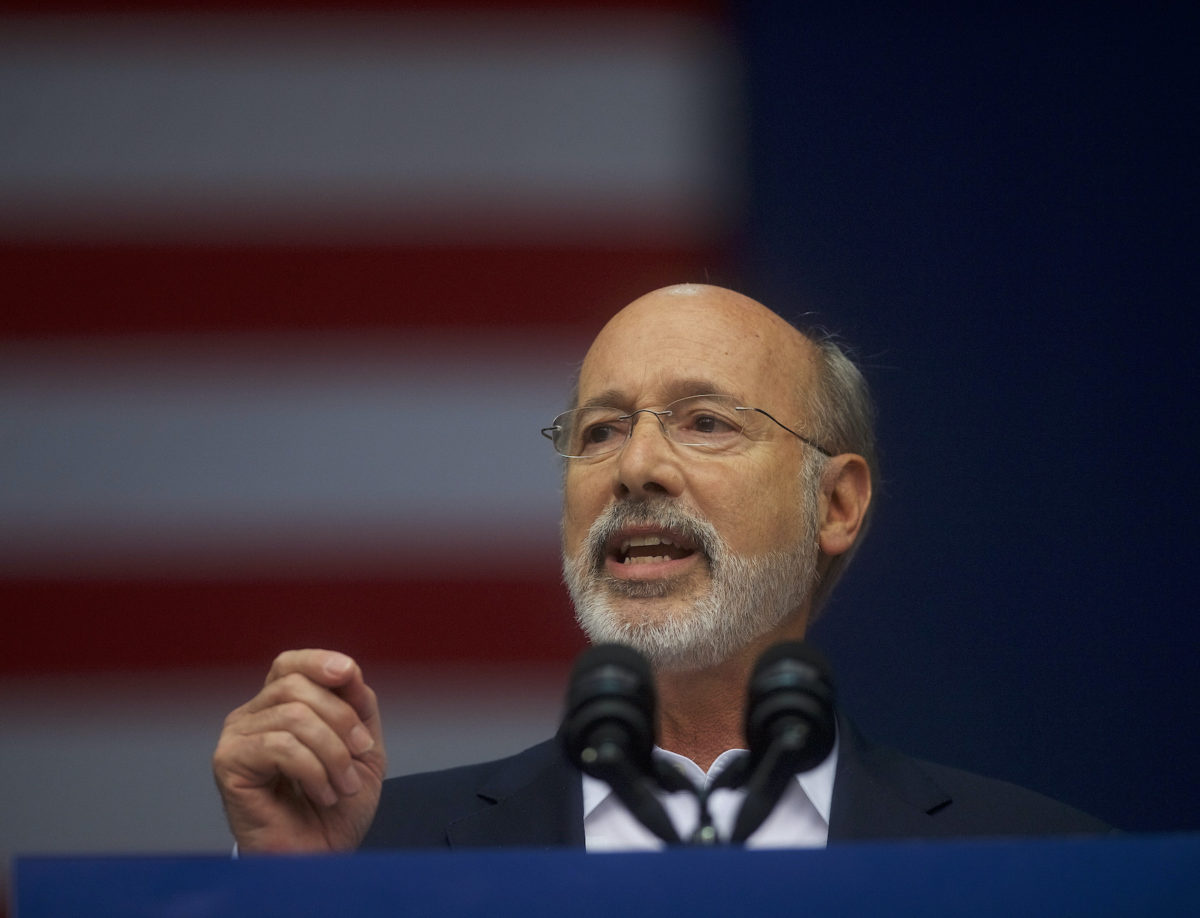

The Office of General Counsel determined that the governor could likely use reprieves to release vulnerable people from prison to control COVID-19’s spread, but the office is advising against it, according to internal emails obtained by The Appeal.

‘It is progressively getting worse, exponentially worse,’ a resident of one halfway house told The Appeal as part of a survey of facilities. ‘Something is going to happen and it’s not going to be good.’

There’s still a chance to make sure some of the most vulnerable people can benefit from the federal stimulus bill.

We can’t allow “violent criminal” rhetoric to justify leaving some of the most vulnerable people in dangerous conditions.

People held in Bristol County are ‘extremely agitated and panicking’ due to unsanitary conditions and overcrowding amid the coronavirus outbreak.

‘Continuing to maintain these youths in this hotbed of contagion poses an unconscionable and entirely preventable risk of harm,’ one lawsuit states.

Decisive action by governors and the President now can save lives — of incarcerated people, correctional and medical personnel, and nearby community members. Business as usual will not.