Sentenced to COVID-19

Spotlights like this one provide original commentary and analysis on pressing criminal justice issues of the day. You can read them each day in our newsletter, The Daily Appeal. These days, I spend a lot of energy thinking about how to keep my child and my parents safe from the coronavirus. But if my child, or […]

|

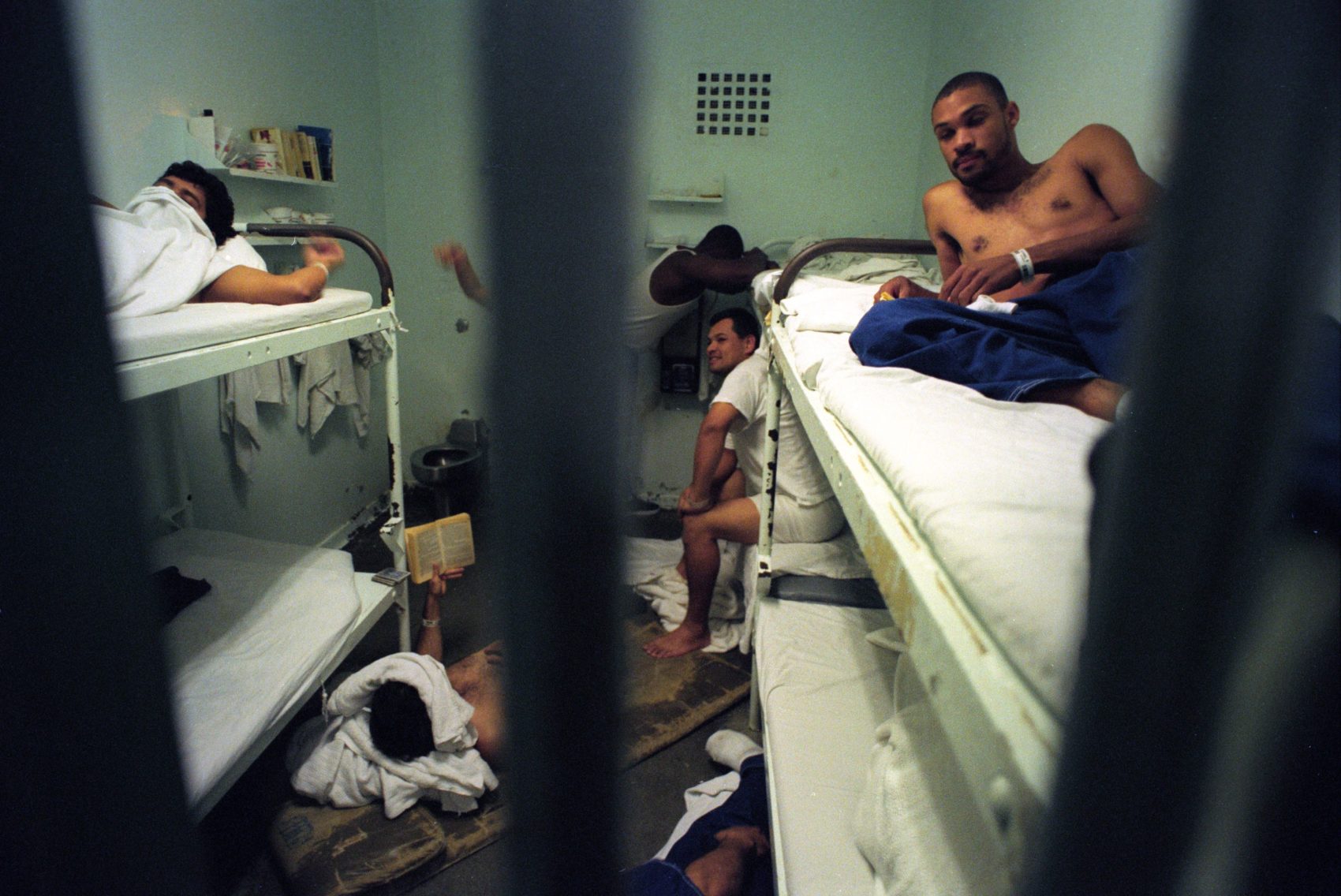

Spotlights like this one provide original commentary and analysis on pressing criminal justice issues of the day. You can read them each day in our newsletter, The Daily Appeal. These days, I spend a lot of energy thinking about how to keep my child and my parents safe from the coronavirus. But if my child, or one of my parents, were incarcerated, I couldn’t do this. I would have no control. Corrections officers, sheriffs, and wardens decide whether to stock up on soap, whether to allow access to sinks, whether to clean common areas or even allow prisoners to scrub their own areas with disinfectant. And, judging from the past, the answer would almost always be no. Prison officials over the years have shown staggering indifference to human life, and the quality of life, depriving prisoners of books, greeting cards, chalk, and, as has recently been reported, hand sanitizer, in the name of “security.” There would be no reason to believe that anyone would be looking out for the health and safety of my family member, because that is not how life works in prisons and jails. “The danger of infection is high in these crowded, unsanitary facilities—and the risk for people inside and outside of them is exacerbated by the ‘churn’ of people being admitted and released at high rates,” writes Premal Dharia in Slate. “In Florida alone, more than 2,000 people are admitted and nearly as many are released from county jails each day.” In 2018, five cases of mumps in immigration detention centers ballooned to nearly 900 cases among staff and detainees. Normally, crowded jails overlook prisoners’ medical problems and find it difficult merely to separate people based on their security classification, Homer Venters, the former chief medical officer of the New York City jail system told Mother Jones. Adding quarantines and sequestration of high-risk prisoners to the task will make managing a COVID-19 outbreak “almost impossible,” he said. “For jails and prisons that are already filthy, and have, generally speaking, a low standard of clinical care, and are trained to take care of one person at a time … this will be a very, very difficult process.” Even if a person is not incarcerated at all but has pending charges and is making regular appearances in court, the outcome might not be different. Courts are crowded, dirty, and similarly indifferent to the well-being of defendants. All of this means that a sentence of a day, a year, or even just an arrest can really mean a sentence to infection. In other systems, criminal punishments are explicitly confined to the loss of liberty itself. The Finnish Sentences Enforcement Act of 2002, for example, states: “Punishment is a mere loss of liberty. The enforcement of the sentence must be organised so that the sentence is [only the] loss of liberty. Other restrictions can be used to the extent that the security of custody and the prison order require.” Finland, Norway, Sweden, and Germany try to make the prison experience as close as possible to the outside environment. In the law review article “Progressive Alternatives to Imprisonment in an Increasingly Punitive (and Self-Defeating) Society,” law professors Sandeep Gopalan and Mirko Bagaric argue that this approach “is achieving outstanding results, with recidivism levels of prisoners after they are released as low as 20 percent.” That’s a fraction of the recidivism rate in the U.S. When it comes to all the punishment inflicted on those in the criminal system in the U.S., the loss of liberty is the tip of the iceberg. There are plenty of corrections officers, police officers, prosecutors, and even judges who miss no opportunity for punishment and degradation. When we draw people into the system, we sentence them to malnutrition. To senseless violence. To neglect. To isolation. To boredom. To labor. We sentence their children to grow up without parents. During my years as a public defender in New York City, not a week went by that I did not talk to a panicked parent, promising to do everything I could to help ensure their child’s safety at Rikers Island. But I couldn’t do much. These clients were all being held in on bail, having not been convicted of anything, but they were enduring punishment that was just as real as anything post-conviction. I spent countless hours on the phone with jail staff, begging them to care. One of my young clients, because of the block where he grew up, was repeatedly attacked by people from a rival neighborhood. Some of the attacks were serious. Once, his throat was slashed. His mother called me every day, and I called the jail every day, trying to get him to safety. If he were out, she said, she could keep him home when he wasn’t working. But with him at Rikers, she could only pray. “I’m not even religious,” she told me, “but what else do I have?” Another client, a transgender woman, was being abused by guards, sometimes sexually. She was having suicidal thoughts. I asked for her to be placed in protective custody—which at Rikers is essentially solitary confinement—and placed on suicide watch. She was isolated and miserable, but the abuse did not stop. Another client, whose girlfriend was going to give birth any day, had a breakdown because he couldn’t be present for the birth of his first child, and couldn’t support his partner. He called me saying he had swallowed a handful of pills he’d found. I spent seven hours trying to convince someone to check on him, but all I got was the same line: “Counsel, we’re on lockdown. There’s nothing we can do.” Another client, who was incarcerated at age 16, quickly developed an ulcer. The judges who were responsible for these people’s incarceration would never have said that they sentenced my clients to slashings, sexual abuse, a breakdown, or an ulcer, but they certainly didn’t order their release when I told them what was happening. These outcomes were not mandated, or intended, but they were certainly permissible. It comes with the territory. There is no reason that we need to accept these outcomes as inevitable. We do not need to shrug our shoulders when told that an outbreak of COVID-19 is probable in jails and prisons. In Denver, for example, and in jails across the country, officials could make an exception to the arbitrary rule that hand sanitizer is contraband and give people a chance to protect themselves inside. We can also just lower our incarcerated population, as Iran did. Yesterday, Brooklyn District Attorney Eric Gonzalez, along with criminal justice advocates and public health experts, asked New York Governor Andrew Cuomo to grant emergency clemencies to elderly and sick prisoners. In Santa Clara County, California, which has had 45 confirmed cases of COVID-19, Sheriff Laurie Smith told the county’s board of supervisors this week that the possibility of an outbreak in local jails was a “huge concern.” Her department is considering “paroling inmates considered ‘criminally low-risk,’ releasing them with ankle monitors, or placing them in alternative custody arrangements such as private residences or residential drug-treatment programs,” reports Mother Jones. And Smith is looking at ways to slow the flow of people into custody in the first place. She said she is planning to ask the probation department to limit probation violations and is encouraging officers to only book suspects for felonies, not misdemeanors. There isn’t much of a silver lining to the COVID-19 pandemic, but it would certainly be an improvement if, in the future, law enforcement and judges consider what a sentence actually entails. |