After Decades in Prison, Should Adults Convicted as Teens Get a Second Chance? A Growing Number of State Laws Say Yes

Second in a three-part series on a teenager with a tumultuous childhood who was sent to die in prison, and where his life would lead. The following narrative was compiled from interviews and court records.

This article is being co-published with The Imprint, a national nonprofit news outlet covering child welfare and youth justice. Read Part One of the series here.

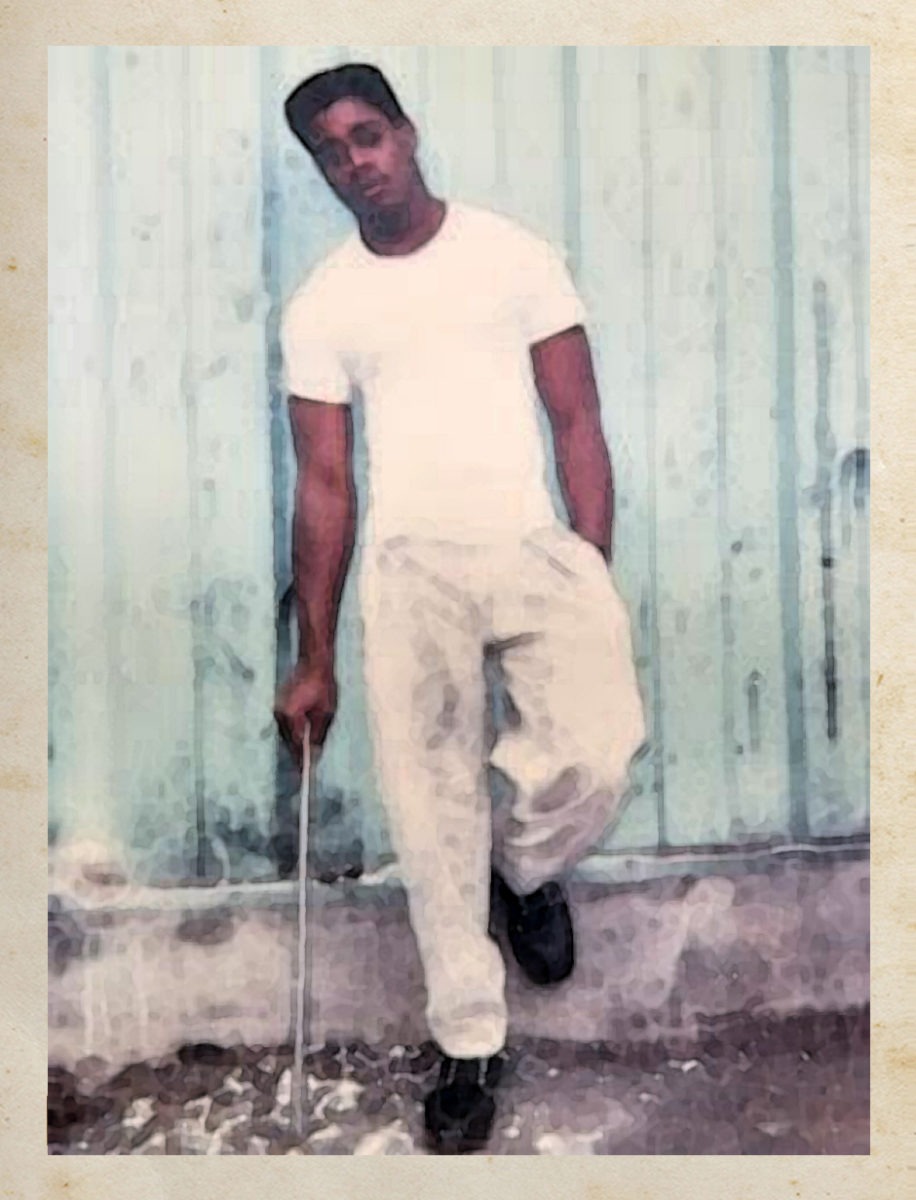

There was, understandably, no sleeping the night before. So when 5 a.m. arrived, Cordell Miller was eager to rise. Wearing his bright orange institutional shorts, he brushed his teeth and performed the customary ablution.

Next, he woke the other men on his unit at the D.C. Central Detention Facility, to kneel on colorful rugs in prayer. Miller converted to Islam a decade into his 97-year-to-life sentence. It was a time when the teen sent to die in prison desperately sought meaning.

He was 49 now and had spent 30 years locked up. On this day, Jan. 21, 2022, prayer was essential. Miller had to prove to Superior Court Judge Craig Iscoe of the District of Columbia that he was far from his 17-year-old self — the one charged with a triple homicide resulting from a drug dispute. It was Miller’s second time going in front of Judge Iscoe.

“What could I possibly say that would convince him that I should be released?” Miller asked himself.

COVID-19 complicated the already-Herculean task ahead. With the virus tearing through the jail where he was being housed at the time, his “re-sentencing” hearing would be held on Zoom. Miller’s friends, family, and supporters would not be filling the courtroom benches, but instead, appear in 40 thumbnail images on a flat screen.

Miller, brown-skinned, bald, and sporting a carefully lined salt-and-pepper beard, was too nervous to smile. But he listened intently, his hands folded in front of him as both sides presented their positions to Judge Iscoe about whether he should be eligible for imminent release.

For decades, there’s been little hope for those sentenced to life in prison in the U.S. But “second look” laws in the nation’s capital, California, Washington, Delaware, Florida, Oregon, and Michigan have changed the prospects for adults such as Miller, some of whom were charged with crimes in their youth — even serious and violent offenses.

Baltimore, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Boston, Philadelphia, Seattle, Prince George’s County, and Brooklyn launched sentencing review units to correct excessive and disproportionate sentences.

Washington, D.C.’s Second Look Amendment Act became law in April 2021. It allows incarcerated people who were convicted before age 25 and have served at least 15 years of their sentence to appeal to a judge for resentencing. The law expands 2017 legislation by extending the age cutoff from 18 to 25, and reducing the required time served in prison from 20 years to 15.

Still, achieving freedom is no small feat. Defendants have to illustrate that they aren’t a danger to society and that a new sentence would be in the “interest of justice.” They must show they’ve been rehabilitated in prison, kept a clean disciplinary record, and provide statements from supporters. Their attorneys must effectively counter arguments from victims and prosecutors.

Before ruling, judges in Washington, D.C., must also consider something that sets these cases apart from more typical parole and resentencing decisions: “The diminished culpability of juveniles and people under age 25, as compared to that of adults, and the hallmark features of youth.” Those features include “immaturity, impetuosity, and failure to appreciate risks and consequences, which counsel against sentencing them to lengthy terms in prison, despite the brutality or cold-blooded nature of any particular crime.”

Miller is one of more than 500 people eligible for resentencing under the D.C. law. According to the Second Look Project—an advocacy group that seeks relief from “extreme sentences”—under the recent iteration of the law, judges have ruled on approximately 67 such cases. Of those, 49 petitioners have been released on supervised probation.

Since the initial 2017 legislation was passed, a total of 145 cases have been decided, and 115 adults were granted release.

James Zeigler, founder and executive director of Second Look Project, describes the law as making D.C. “a more just and equitable place, and to try and remediate the mistakes of our overly punitive past.”

Federal prosecutors have argued the opposite. They say laws like these free “dangerous criminals” and deny victims a “sense of finality.” Describing the second look law in 2019, the U.S. Attorney’s Office of the District of Columbia said it “ignores how painful this process is for victims and will drastically increase the number of victims who must be re-traumatized.”

Prosecutors stated in a press release that it would make more than “500 violent criminals (including many rapists and murderers) immediately eligible for early release.” The prosecutors singled out judges’ ability under the then-pending legislation to release someone “despite the ‘brutality or coldblooded’ nature of the offense.”

‘An entirely different person’

At Miller’s January hearing, Safa Ansari-Bayegan, one of his court-appointed attorneys, presented first. Without minimizing Miller’s actions or the harm he caused, she told the court why — after serving 30 years behind bars — he is an ideal candidate for release.

“He’s an entirely different person today before the court, nearly 50 years old, than the misguided 17-year-old who took the lives of John Huff, Lester Cowen, and Adrienne Edmonds, and who also recognizes that he caused a lifetime of pain to their loved ones,” she said. Miller has channeled his “deep regret and his remorse into bettering himself and bettering those around him.”

Marc Howard, a professor of government and law at Georgetown University, where he directs the Prisons and Justice Initiative, described Miller as “extraordinary,” and “a committed leader.” Miller attended one of Howard’s classes in the Georgetown Prison Scholars Program, a class for incarcerated individuals and Georgetown students. Howard told Judge Iscoe that he’d happily offer Miller employment, would welcome him into his home, and introduce him to his wife and children.

Miller’s legal team also presented a psychiatric evaluation, letters, and additional witness testimony that drive home the point: He doesn’t pose a future danger to society.

Deputy District Attorney Pamela Satterfield, however, offered a thunderous rebuttal. Recalling prior testimony from a relative of one of the victims, she said they would be “horrified” that Miller wanted to get out early.

Five years earlier, the prosecution noted that Miller received a 37-year sentence reduction under a Supreme Court ruling that found juvenile life-without-parole sentences to be unconstitutional. That was more than enough relief, Satterfield said: He could still be released before he turned 80.

“Now we’re getting down to 11 years per human being, and we just think that further reduction is not in the interest of justice in this case,” she added.

Satterfield also noted a different danger: 41 months that had been tacked onto Miller’s life sentence in 1996.

Context is important for understanding that crime, his attorneys argue: At the time, his original offense had prompted several retaliatory death threats. Miller was stabbed in his head and shoulder by associates of his victims, according to court reports, and one of his co-defendants was murdered by a victim’s nephew. Then in 2007, a prisoner threatened to kill him. In a fight that followed, Miller stabbed the man.

Public safety arguments to keep people with lengthy terms locked up routinely challenge sentencing relief efforts in courts and legislatures. Lawmakers in at least 25 states have introduced Second-Look-style bills like the one in D.C., but have been unable to get them passed.

Challenges to Second Look laws abound

Opponents of early releases insist that people imprisoned for violent crimes, no matter their age at the time the crimes were committed, will likely re-offend if they are freed, and should carry out their full sentences.

In 2019, even before the bill became law, the U.S. Attorney’s Office of the District of Columbia condemned D.C.’s second look legislation — an expansion of the 2017 Incarceration Reduction Amendment Act (IRAA).

An uptick in violent crimes committed by adults during the pandemic has fueled opponents of sentencing reforms. Between 2019 and 2020, the number of murders nationwide rose by 30 percent, according to federal crime statistics, marking the largest recorded jump in a one-year period since the FBI began releasing annual figures in the 1960s. However, the violent crime numbers were still well below the highs of the 1990s. There is a lag in reporting crime trend data, but some studies show the murder rates from 2020 to 2021 have continued to climb slightly in some cities.

In such a climate, judges can be skeptical.

Attorney Destiny Fullwood-Singh, co-executive director of the Second Look Project, concedes that some people “aren’t ready to come home” from prison, and some judges’ denials are warranted. Yet in too many cases, she added, judges discount the science showing that human brains develop well into a person’s 20s—causing impulsivity and an inability to weigh consequences—and they chalk criminality up to a hallmark of a defendant’s character. Others simply don’t consider youth at the time a crime was committed to be a reason for leniency, she said.

Under the first D.C. sentencing reduction law for juvenile offenders—when the age cutoff was 18—petitioners had a 90-percent success rate in achieving release, she noted. But the newer law describing a youthful crime as one committed by those 25 and younger has been a tougher sell in court.

There is no evidence that criminal justice reforms are connected with the recent uptick in adult homicides. Criminologists question whether it has more to do with pandemic lockdowns, a dramatic increase in gun sales, and social unrest. Murder rates have increased in cities run by Republicans and Democrats, progressives and conservatives.

And of the 115 people released under the legislation in D.C., just four people have reoffended, according to the Second Look Project.

Fullwood-Singh said, still, attorneys face resistance from some judges and prosecutors, “maybe it’s COVID, maybe it’s this kind of perceived rise in crime, maybe it’s everything. But while the success rate for IRAA is inspiring, the implementation of this law has not been without its challenges.”

Immature and malleable

Before he was arrested on murder charges in D.C., Miller had grown up with turbulence and successive losses. His father was killed, and his early caregiver in Jamaica — his beloved grandmother — initially left for the U.S. without him.

Then, when he came to join her in Brooklyn, New York, that lasted only a while before she grew too ill to care for him. He moved in with his mother but lived in a violent and abusive household that drove him to act up. Miller lived in a succession of group homes and a juvenile detention center and ended up living on the streets.

His court records describe the impact of trauma on youth with backgrounds like Miller who “often become destructive, have distorted perspective, and poor self-regulation.”

In a series of interviews over the past year, Miller described his behavior as a teenager: he was immature, impulsive, and cowardly. But he was also battling a history of childhood traumas. In aggregate, these factors aren’t necessarily predictors of a criminal trajectory. But numerous studies show they are all high-risk factors.

Miller’s first crime was committed at age 13 with a group of schoolmates: stealing another boy’s winter coat. His next: a 2001 triple homicide.

This was the backdrop to what would become Miller’s life sentence in prison.

Laws that offer a pathway to release for incarcerated people like Miller are supported by a growing body of scientific research. “Emerging adulthood”—defined as ages 18 to 25—is considered a “distinct developmental stage,” in which adult punishment is considered unfair and ineffective, according to research compiled by Columbia University’s Emerging Adult Justice Project.

Youth are also malleable, amenable to rehabilitation, and have a greater likelihood of maturing from their behavior, numerous studies show.

The judiciary has responded. Citing emerging brain science, the Supreme Court has issued six decisions since 2005 classifying minors as less culpable than adults for their criminal conduct. The highest court has also barred the death penalty for youthful offenders, deeming it cruel and unusual punishment, and limited life without parole to extreme cases.

Still, racist stereotypes and exaggerated fears continue to permeate U.S. society.

The recent rise in adult violent crime, for example, has so far not held true for juveniles, federal justice officials say. Youth crime rates have fallen by more than half over the past two decades and continue to drop — including juvenile arrests for serious offenses including murder, rape, robbery, and aggravated assault, according to federal crime data through 2020, the most recent available.

Yet Black people, like Miller, continue to be overrepresented in the juvenile justice system. Nationally, emerging adults account for 1 in 10 members of the general population, yet they make up 23 percent of all arrests. In D.C., they account for 11 percent of the general population but represent 26 percent of the average daily jail population. The disparity is even worse for Black D.C. residents: They represent nearly 98 percent of incarcerated people serving the longest prison terms, who were sentenced as emerging adults.

My hands were trembling

Meanwhile back in jail, while he awaited word, he sat in an office space and reflected. Miller’s 30 years behind bars were marked by violence, growth, working, praying, mentoring, and finding love as he shuffled through nine federal prisons.

He worked to climb out of the violence, learning to stick to himself, lean into his faith and be of service. He was not allowed to take certain classes because of his life sentence and because he is not a U.S. citizen, but he took every class he could, including college courses. He worked in various jobs, from janitor to health clinic orderly. And he found love. In 2015, Miller started a relationship with Tyresa Washington, 46, and later got engaged.

On this January day, he’s a mentor in the Young Men Emerging program at the D.C. jail. The program, which was founded by incarcerated men, pairs longtime prisoners with newly incarcerated emerging adults. The young men in the program have access to education, one-on-one mentoring, job training, financial literacy, and more.

Living in this unit affords Miller freedoms that the rest of the jail only dreamed of. Not only did he have access to a computer and phone when he wanted, he met congressional leaders, lawyers, and judges who came to visit the program. These were all novel firsts.

“Throughout my confinement, that’s the most freedom I’ve ever had. The most accessibility to the outside world that I’ve ever had. The most respect from staff that I’ve ever experienced,” he said. “I actually felt as though I was not locked up. I felt like I was a civilian.”

These liberties were monumental. But they did not compare to the reward he had long felt from relationships he developed with younger incarcerated men. Sometimes it was as simple as offering a listening ear, other times he peaked their interest by creating rap battles or basketball competitions. It was not until he arrived at the D.C. jail that he became a mentor in a formal capacity. Miller often cautioned the young men to use the opportunities offered in the program — and expanded upon them. At one point he launched a late-morning reading group called “Book Crushers.”

Finally, Miller could offer the guidance, concern, compassion and cool temperament he wished he had as a young person.

“I tried to fulfill that void that I think that was in their lives,” he said. His goal was to try to be understanding and relate to the boys through both versions of himself: the misguided youth and the rehabilitated man.

As much as he loved helping the boys, they also fed his spirit. “I need y’all as much as y’all need me,” he would tell them. Miller was eager for freedom but did worry about his mentees.

He’d spent nearly a year with them while awaiting his re-sentencing trial, and might soon be leaving. The idea of freedom was exhilarating, but it was also fraught. He knew his absence could cause his young charges to spiral, and act out. And because of his immigration status, he feared he might leave prison for immigration detention.

Sure enough, a few weeks after his January hearing, Miller got word of the judge’s decision. His petition had been granted. He was working on the computer when an officer came to tell him he was going home.

Miller tried to call his fiancée. “My hands were literally trembling,” he recalled. “It took me about four to five minutes to dial her number.”

The day Miller left, he wore the orange uniform for one last time. It’s customary for anyone leaving prison to give their belongings to those that will be left behind. He gave the bulk of his things to the two mentees, both Muslim, that he was closest to. One mentee was gifted his cosmetics: soap, toothpaste, deodorant, toothbrushes, lotion, shampoo, and hair grease. The other, who Miller describes as financially less fortunate, received his commissary: Kool-Aid packets, soups, rice, chips, canned tuna, oysters, crackers, pastries, and all kinds of condiments.

Afterward, all the men in the unit gathered to say a few words. Miller held a net bag filled with pictures and legal paperwork. He placed his hand over his chest as he listened to his friends send him off. The men all sang a farewell song and shared a few words as Miller backed out the door dancing.

When the song was over, they said, “get out of here, you’re a free man.” One young man said, “freedom is real, now the real is free.”

“He was a good mentor,” one officer said. “We’re going to miss him. The young’uns are going to miss him. But I know he’s going to make it out there.”

His fiancée, Washington, waited outside in the car. But instead of receiving the usual sweatsuit to go home in, he was handed a blue jumpsuit. For the next three months, he’d be locked up yet again, this time by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Find out where Cordell Miller goes next. Read the postscript to Miller’s story in part three, publishing Feb. 13.

This story was supported by the Fund for Investigative Journalism.