After More Than 25 Years Behind Bars, He’s At High Risk For Coronavirus. Now He’s Going Home

John Wesley Parratt Jr. was scheduled to appear before the parole board in July. After the novel coronavirus arrived in San Quentin State Prison, he feared for his health.

Juan Moreno Haines is an award-winning incarcerated journalist and a member of the Society of Professional Journalists.

John Wesley Parratt Jr., better known as “Yah Ya,” has diabetes. He’s overweight and has high blood pressure. A couple years ago, the 67-year-old incarcerated African American survived a heart attack. Before that, he had prostate cancer that’s now been in remission for 12 years. All these ailments developed while behind bars for more than 25 years. Parratt and this reporter have shared a cell in North Block in San Quentin State Prison for more than eight years.

After the novel coronavirus arrived in San Quentin, Parratt feared for his health. So far, there are six confirmed staff cases of COVID-19. No prisoners have tested positive for the virus, which causes COVID-19, but fewer than 2 percent of people held there have been tested.

“I’m scared to death. Coronavirus affects the whole world. I’m afraid for my friends and family on the streets,” Parratt said. “I’m on chronic care because of all my health issues.”

On April 22, Parratt stood in a pill-pass line for diabetes medication. About a dozen aging prisoners seeking medical care stood with him. The line forms three times a day in North Block.

“A couple years ago I was going to work and realized that my vision was getting blurry. A few days later, I told one of the correctional officers that I was feeling dizzy. He began to escort me to the hospital, but I passed out before we got there. A wheelchair came to pick me up. At the hospital the tests showed that my blood sugar was around 500. It should have been around 90,” Parratt said.

Parratt now takes several medications daily: two glipizides to lower blood sugar, glucose to raise blood sugar when needed, one metformin to balance blood sugar, and one amlodipine besylate for high blood pressure.

To lessen the effects of overcrowding in North Block, Parratt stays in his cell as much as possible. More than 750 prisoners are double-bunked in the unit’s 414 cells. That’s over 180 percent of designed capacity.

Parratt is a safety coordinator with the Prison Industry Authority, which employs people while they are incarcerated. The administration relies on his know-how to train new employees and keep the shop at state and federally mandated Occupational Safety and Health Administration standards. That makes him an essential worker.

Safety coordinator is only one of Parratt’s specialties. He’s a baseball manager at San Quentin. He’s a mentor in several self-help groups. He’s a cook.

And he has been free of disciplinary action for his entire incarceration. Not a single rule violation—no write-ups in 25 years.

“I just did my program every day—staying out of the way and quiet. Being older had a lot to do with it,” Parratt said. “I played a lot of sports and stayed active. Hearing about people going to the board and how getting into trouble got them denied made me not want to be one of them. I wanted to go home.”

California’s top prison administrator, Ralph Diaz, took notice of Parratt in January 2019 and asked a Sacramento judge to reconsider his 58-year-to-life sentence for kidnapping.

“Inmate Parratt is commended for remaining disciplinary free during his current incarceration of nearly 24 years. He has continuously programmed in a positive manner and has taken full advantage of rehabilitative opportunities to successfully transition back into society,” Diaz wrote. “I recommend the inmate’s sentence be recalled and that he be resentenced.”

The county district attorney did not oppose Diaz’s recommendation.

“After reading the letter about three times, I was shocked,” Parratt said. “I called my girlfriend to let her know about it and shared the letter with my cellie.”

Parratt was scheduled to appear before the parole board in July. A forensic psychologist makes a risk assessment for the board commissioners to consider.

When Parratt was evaluated on April 20, he talked about his childhood, family life, what led up to the kidnapping, what he did while in prison, and his plans if he were released.

“I said that I came from an excellent family. My parents were married for 55 years, and put me and my sister through college. I have four children—two boys and two girls. My college days were interrupted by my pursuit of baseball. I’ve had good jobs. My problems came from my own insecurities and bad decisions, including drug use, which led to infidelity and my crime.”

He said he met the crime victim at one of his jobs.

“I committed this crime against an innocent woman,” Parratt said. “I did it out of an irrational, drug-induced fear.” He added, “I decided to use drugs, so using them does not excuse what I did. My journey began when I started addressing why I was using drugs.”

“I feel horrible, which is why I know that I’ll be in recovery and making amends for the rest of my life,” Parratt said.

Prison administrators and volunteers who work directly with Parratt support his release.

Jon Gripshover, an instructor in a computer coding program at San Quentin, has known Parratt more than six years.

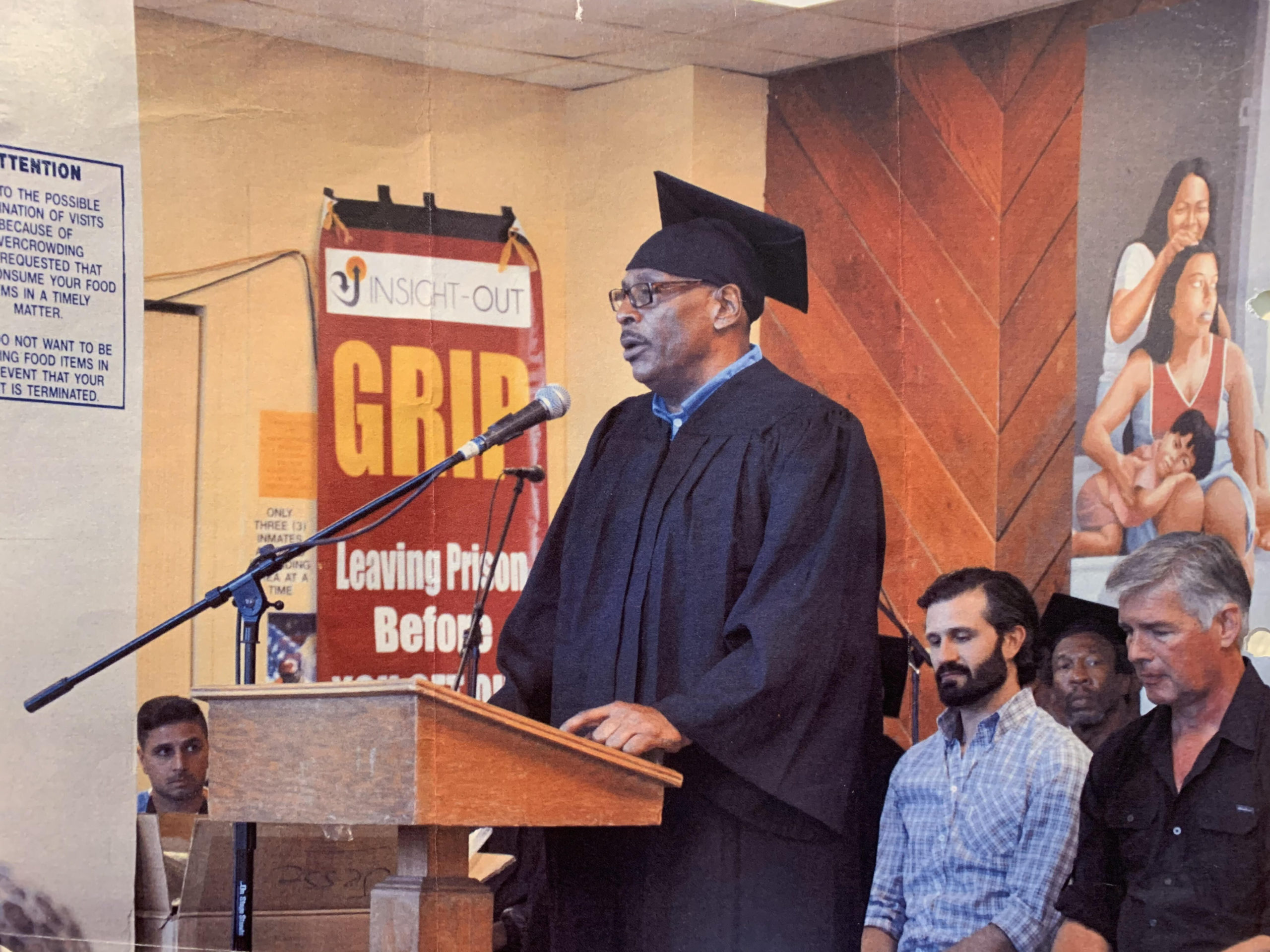

“I’ve determined that Mr. Parratt has rehabilitated himself based on the following programs I’m personally aware he partakes in: [The restorative justice program] GRIP, IMPACT, anger management, Alliance for Change (as mentor), Elite Program Islamic Studies, Hope for Strikers, Coalition for Justice, and baseball manager of San Quentin A’s. These programs require a great deal of commitment and focus, which is exactly what our society needs in order to reduce the crime rate and transition back smoothly,” Gripshover wrote in a support letter.

Michael Kremer, director of the San Quentin baseball program, has known Parratt for four years. He said, “Yah Ya has shown a superb level of commitment to the baseball team, evidenced by the fact that he has been involved as a coach in the program for 10 years.” Parratt is “a well-regarded cook,” Kremer added, “and he frequently shares meals with the team with food from canteen, helping to build social cohesion among the team members and bringing them closer together, off the field as well as on the field.”

Judge David De Alba listened to Parratt’s case via video conference at 9 a.m. on April 24. The victim said in her statement to the court that if Parratt turned his life around, she’s happy, but she still has reservations about his release. She hopes he can go on to live a good life, for her sake, his sake, and society’s sake. She does not want to see him revert to his old ways.

It took De Alba 15 minutes to decide that it was time for Parratt to go home with time served. He’ll have a job waiting for him after his release.

“I’ll work as a health and safety coordinator for a company in San Ramon, California,” Parratt said. “Of course, I’d like to get married, take a little vacation. I’d like to cook some good meals for my wife and enjoy her company.”

He said his parents died while he was incarcerated, and he wants to see their graves. He has a lot of catching up to do with his sister and children. And he wants to visit Mississippi, where his aunt lives, to reconnect with his roots.