The Case For Universal Rental Assistance

Expansion of an existing federal rental subsidy program, the Housing Choice Voucher, could stabilize housing for millions of households.

This research and analysis is part of our Discourse series. Discourse is a collaboration between The Appeal, The Justice Collaborative Institute, and Data For Progress. Its mission is to provide expert commentary and rigorous, pragmatic research especially for public officials, reporters, advocates, and scholars. The Appeal and The Justice Collaborative Institute are editorially independent projects of The Justice Collaborative.

Rodrigo Lopez, a handyman and debris hauler in San Francisco, thought he had averted a housing disaster. He and his family had been evicted last year when their home was knocked down to make way for development, but they soon found another studio apartment, according to the San Francisco Chronicle. “It was a new start for us,” he told the paper. “I thought everything was going to be OK — then coronavirus came along.”

Because of the pandemic, businesses have shut down, unemployment has soared, and Lopez’s work has disappeared. Without any income he’s been unable to pay rent, putting his family back into the precarious situation he thought he had escaped.

For others, the crisis presents an agonizing choice: pay rent or eat. Terra Thomas, a florist in Oakland, decided to withhold her $833 rent due in April.

“This could last a long time and be really, really serious, so I don’t want to be asking myself in a few months, ‘Why did I give away my last few paychecks to rent?,’” Thomas told the New York Times. “I need to know that I can eat and pay for health care.”

These scenes are playing out across the country as the coronavirus magnifies the nation’s affordable housing crisis. Even before the pandemic, millions of households spent far more on housing than they could afford, foregoing other necessities to keep a roof over their heads. Now the crisis has reached millions more. Some jurisdictions have deployed emergency stopgap measures such as temporary rent freezes and eviction bans, but renters need more than delay. What happens when, after emergency orders are lifted, all the back rent comes due?

As it turns out, the United States already has a tool that can help remedy the problem: the Housing Choice Voucher (HCV), a federal rental subsidy program that provides vouchers to cover rent that exceeds 30 percent of a person’s income. HCV works. Every year, voucher programs make housing affordable to about 2.3 million households. They reduce homelessness and allow recipients to devote more of their income to food and healthcare.

The problem is that HCV has been strictly rationed below the demands of America’s housing crisis, with not enough vouchers to go around. Before the public health emergency, the program served only about one-fourth of all eligible households, and these households are typically very poor. In 2019, for example, the average income of HCV participants was just $14,711 per year, an amount far too low to afford market-rate rent.

The HCV program can, and should, be expanded to meet the demands of the current crisis. It should become an entitlement immediately available to eligible households so that people can remain housed and the millions of people who are currently homeless can be eligible for safe and stable housing. Expanding the program now will provide relief for those experiencing a longstanding housing crisis while also protecting communities from a deadly and highly contagious disease.

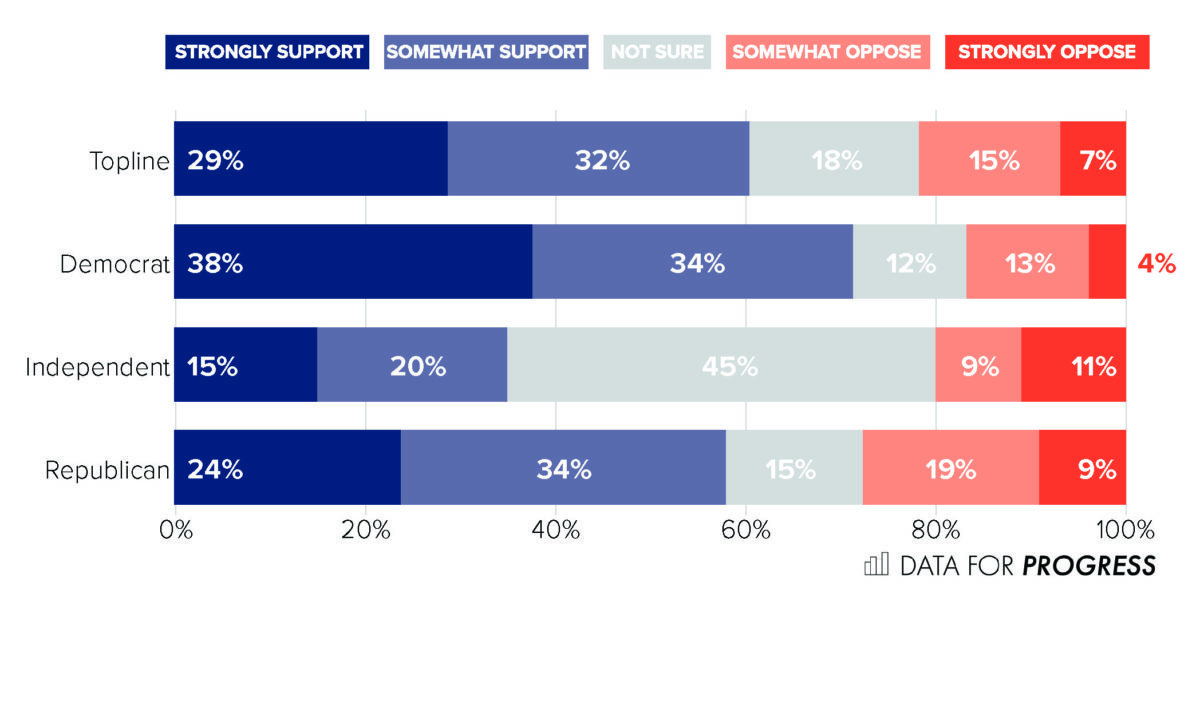

It is also overwhelmingly popular. Polling by Data for Progress shows that voters support HCV expansion by a 35 point margin — with 61 percent of likely voters, including 58 percent of Republicans, in support, compared to 25 percent who oppose.

Before the coronavirus pandemic, nearly half of all renters in the United States paid more than 30 percent of their income on rent, and nearly one-quarter spent 50 percent or more. Among low-income renters, the problem was worse — with 55 percent of all renters earning up to $30,000 spending half of their income on rent, including 71 percent of all renters earning up to $15,000. More than 1.4 million people experience homelessness during the course of a year.

In the last two months, all available signs indicate that even more people will experience housing insecurity. More than 33 million people have filed for unemployment since mid-March as the unemployment rate rocketed from 4.4 percent in March to 14.7 percent in April. Prolonged unemployment will likely push many more renters into arrears since they have little savings to draw upon.

Before the pandemic, several Democratic presidential candidates, including Joe Biden, advocated for making HCVs available to all eligible renters, as similar programs are available in the UK, Australia, and some parts of Canada. Congress should incorporate this recommendation in its next COVID-19 relief legislation.

Expanding the HCV program to cover all low-income households, including the newly unemployed, would not only enable millions of families to stay housed, it would also enable private and nonprofit landlords to pay their mortgages and avoid foreclosure, pay property taxes so that local governments can provide essential services, and keep their employees on their payroll. Rent freezes and eviction moratoria may stave off immediate disaster for renters, but they only delay the question of how they can pay rent, and do nothing to prevent landlords from defaulting on their mortgage and tax payments.

More widely available HCV benefits would help the vulnerable populations who need them most. It would help reduce homelessness, by reducing the incidence of eviction and enabling people who are currently homeless to secure permanent housing. It could also ease the reentry process for people released from prison and jail by helping them obtain affordable housing. In order to be effective, exclusions based on criminal records should be lifted. Similarly, recent exclusions barring assistance if any member of the household is undocumented must also be lifted. The goal is to safely house people while also supporting landlords and other housing providers in maintaining the nation’s current housing stock. Excluding those most in need directly undermines that goal.

The HCV program currently costs about $24 billion a year. If the program were made available to all eligible households, it would have cost about $60 to 70 billion before the coronavirus, and perhaps as much as $100 billion now. That’s a lot of money, but it is a fraction of the total amount needed to sustain the country through the crisis. It also approximates what the U.S. currently spends on mortgage interest deductions and other tax breaks for homeowners. Moreover, reducing the percent of income people are forced to pay for rent leaves them with money to spend at local businesses and grocery stores. When people do not have to spend all of their money on rent, they have money to invest in the local economy, uplifting everyone in the community at a crucial moment of economic crisis.

To be most effective, the HCV program would need certain modifications tailored to the current crisis. HUD has already suspended the requirement that units be inspected before families can move in, which cuts down on time and lets people get housing right away. The program should also be adjusted to cover back rent.

With the HCV program, the U.S. can stabilize housing for millions of households. The program is already in place; it would only need to be ramped up — a solution that is popular among voters of both parties. Ideally, the program should be available to all who need it.

The $3 trillion HEROES Act introduced on May 12 by House Speaker Nancy Pelosi is a welcome start. It includes $100 billion in emergency rental assistance that would achieve many of the benefits of making Housing Choice Vouchers available to all eligible households. But this support would only be temporary, lasting no more than two years. Our proposal would provide both short- and long-term support to low-income renters, and protect them from future economic shocks.

Methodology

From 5/8/2020 to 5/9/2020 Data for Progress conducted a survey of 1235 likely voters nationally using web panel respondents. The sample was weighted to be representative of likely voters by age, gender, education, urbanicity, race, and voting history. The survey was conducted in English. The margin of error is ± 2.7 percent. Respondents were asked: “Currently, the federal government provides Housing Choice Vouchers, which are intended to help people pay for part of their rent if they are otherwise unable to afford it. Program participants must pay 30 percent of their income in rent, but the program provides vouchers to help renters cover housing costs that are above that 30 percent. Before coronavirus, only about 1/4 of eligible people used the program for a variety of reasons, most notably, many landlords refuse to take the vouchers. Do you support or oppose the expansion of the Housing Choice Vouchers program?”

Kirk McClure is a professor of urban planning in the School of Public Affairs and Administration. His teaching and research examines housing market behavior and evaluates federal affordable housing programs. His research has been supported by multiple grants from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). He was Scholar in Residence at HUD’s Department of Policy Development and Research.

Alex F. Schwartz is Professor of Public and Urban Policy at the New School. He served as Program Chair of Public and Urban Policy from 2001 to 2012. He holds a doctorate in Urban Planning and Policy Development from Rutgers University. Professor Schwartz’s research centers on housing and community development, including public housing and other affordable housing programs, mixed-income housing, fair housing, and community development corporations.