Prisons Crack Down On An Opioid Treatment Drug, Endangering Lives

Few of the prisons trying to stem flow of contraband Suboxone offer substantial opioid treatment programs.

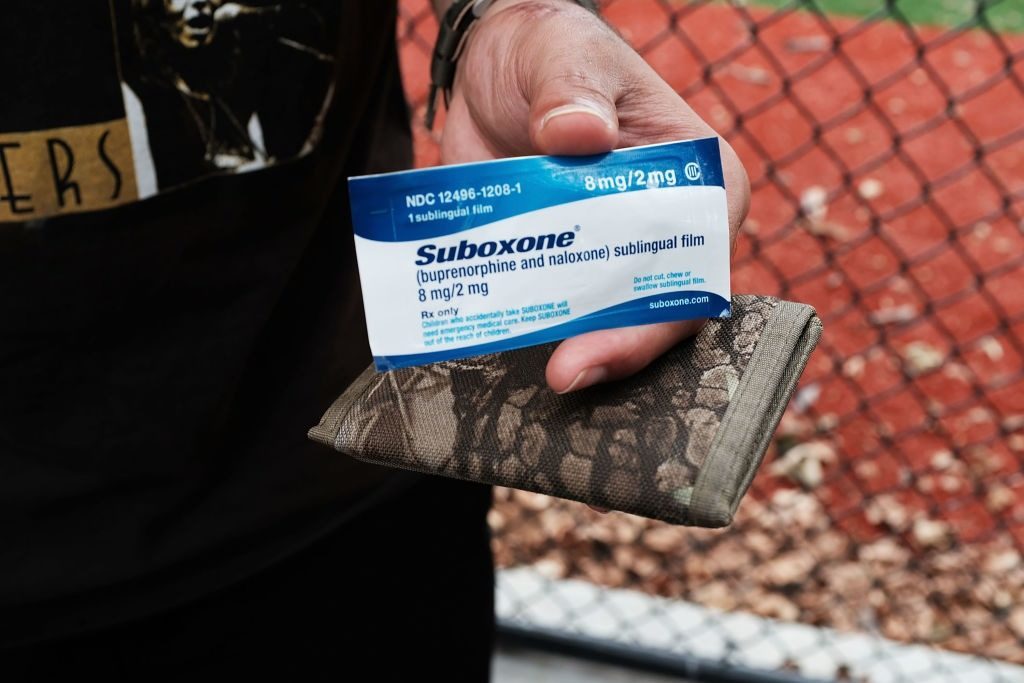

Maryland banned prisoners from holding or cuddling family members. Pennsylvania is restricting prisoners’ access to book donations. Colorado prisons have forbidden greeting cards and any mail containing drawings. All of these measures were taken in the name of stemming the flow of contraband Suboxone, an opioid treatment drug that helps lessen withdrawal symptoms.

Yet few of these prisons offer substantial rehabilitative programs for prisoners in need of treatment for substance use disorders.

Medical professionals endorse medication-assisted treatment programs, which use a combination of mental health counseling and medication (such as methadone, Suboxone, buprenorphine, or naltrexone) to prevent opiate overdose. Though studies have shown this approach reduces overdose deaths in prisons, prisons have been slow to adopt substantial medication-assisted treatment programs. While some prison systems refuse to offer any such treatment programs, others have limited their program to only one medication.

Denying treatment has proved fatal in jails and prisons across the country. “People who re-enter the community after a period of incarceration are 50 to 120 times more likely to overdose and die than the general population. This is because they go through detoxification and withdrawal, diminishing their tolerance,” Leo Beletsky, a professor of law and of health sciences at Northeastern University, told The Appeal.

Forced, sudden withdrawal is also deadly. In May, Kentrell Hurst died in the Orleans Justice Center jail while detoxing from opiates and alcohol. In January, Frederick Adami died because of opiate withdrawal complications at Bucks County Correctional facility in Pennsylvania. In Colorado, 25-year-old Tyler Tabor died of dehydration at Adams County jail outside Denver after experiencing painful opiate withdrawal symptoms for three days in 2015. And in Utah, Madison Jensen died in 2016 of cardiac arrhythmia due to opiate withdrawal and dehydration. Nearly all withdrawal deaths, especially those due to dehydration, are preventable.

If he had not reached a settlement with the Maine Department of Corrections last month, Zachary Smith could have been one of the casualties. Smith, who has been in recovery for five years, is preparing to start a nine-month stint in the Aroostook County Jail, which has a ban on medication-assisted treatment.When he entered the prison system, Smith would have been cut off from buprenorphine, the medication that has helped him manage his chronic illness. The ACLU of Maine argued on Smith’s behalf that the lack of medication-assisted treatment programs violated Smith’s rights under the Americans with Disabilities Act, which lists drug and alcohol addiction as a disability. Additionally, they alleged that the painful withdrawal symptoms he would undergo would constitute cruel and unusual punishment, a violation of the Eighth Amendment.

“He was going to go from being a person with an addiction problem who is in recovery to somebody who is taken off their medication and left to try to manage their problem on their own—which is incredibly hard to do and not the way that doctors and the medical community think this should be treated,” said Zachary Heiden, legal director of ACLU of Maine. “To go from being on medication-assisted treatment to being cut off from that treatment, as prisons and jails frequently do, is incredibly painful and potentially life-threatening.”

Smith will continue taking buprenorphine when he goes to prison. But, the lawsuit settlement doesn’t extend to the other 2,500 people incarcerated in the Maine prison system. The state’s Department of Corrections commissioner, Joseph Fitzpatrick, said the agency had no plans to provide medication-assisted treatment to the rest of its prisoners and called Smith’s situation a “unique case.”

Last year, Suboxone was the most common contraband found in the Maine prison system.

Prison officials justify the crackdowns by arguing that Suboxone, which is prescribed by a doctor, can be abused in large doses to produce a high similar to other opioids like heroin. But contraband is far more likely to be smuggled in through correction officers, who are less scrutinized than prisoners’ families and visitors. States have busted ring after ring of corrections officers who trade contraband drugs, alcohol, phones, and other banned items in exchange for bribes.

And while multiple prison and jail systems—such as in Virginia, Maine, and Pennsylvania—have come down hard on prisoners in the name of restricting contraband drugs, these same states fail to offer meaningful channels for the majority of their prisoners to access necessary medications.

To justify ending book donation programs and moving to an electronic book system, the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections posted a photo on Twitter last month of a book sent to the prison from a bookseller that had strips of Suboxone in it. Pennsylvania offers only naltrexone to most of its prisoners for its medication-assisted treatment program (pregnant people receive methadone). Amy Worden, a spokesperson for the agency, said it will begin offering buprenorphine (both Suboxone and Sublocade) as a pilot program next month in two or three of its 24 prisons.

Similarly, the Virginia Department of Corrections posted a photo on Twitter showing orange Suboxone strips. The tweet alleged that a visitor had attempted to smuggle in Suboxone strips by hiding it in her genitals. Days earlier, the agency banned female visitors from wearing tampons or menstrual cups; however, Brian Moran, the state’s secretary of public safety and homeland security, suspended the policy on Sept. 25 “until a more thorough review of its implementation and potential consequences are considered.”

In July, Virginia prisons began a pilot medication-assisted treatment program that offers one drug: naltrexone. Naltrexone does not treat withdrawal symptoms. Prisoners in the program will receive an injection of the drug right before being released and are required to participate in post-release drug treatment services. However, for the majority of those incarcerated in Virginia Department of Corrections, the pilot medication-assisted treatment program will not be accessible. Indian Creek Correctional Center and Virginia Correctional Center for Women are the only two of the state’s 38 prisons that have the program. (People incarcerated at three out of five of the Community Corrections Alternative Programs are also eligible.) Since 2015, at least 12 people have died of overdoses in Virginia prisons, making opiate treatment programs in the state an even more pressing concern.

Meaningful intervention, according to Beletsky, requires making medication treatment programs accessible to all prisoners upon entry into prison. Because of the subtle differences in medication treatments and possible side effects, it’s important that prison and jail systems offer as many options as possible.

“Ideally prisons and jails will continue the treatment that somebody is already receiving. … Because anytime you change somebody’s medication, there’s potential problems,” Heiden said. “Each of these drugs works on the brain in slightly different ways, and the medical standard of care is not to simply swap one for another—just as you would not simply swap Celexa for Zoloft. One medication may be less effective than another, or it may cause different side effects.”

Prisons that have committed to the medication-assisted treatment approach have seen promising results. Rhode Island’s Department of Corrections, which started making three opioid treatment drugs available in mid-2016, quickly found that fewer prisoners died from overdoses after being released.

The Maine ACLU and other legal experts argue that states that do not to provide medication-assisted treatment programs in their jails and prisons are violating the Eighth Amendment, as they say denying necessary medication amounts to cruel and unusual punishment. “Prisons and jails are obligated to provide medical treatment for people in their custody and medication-assisted treatment is medical care,” Heiden said.