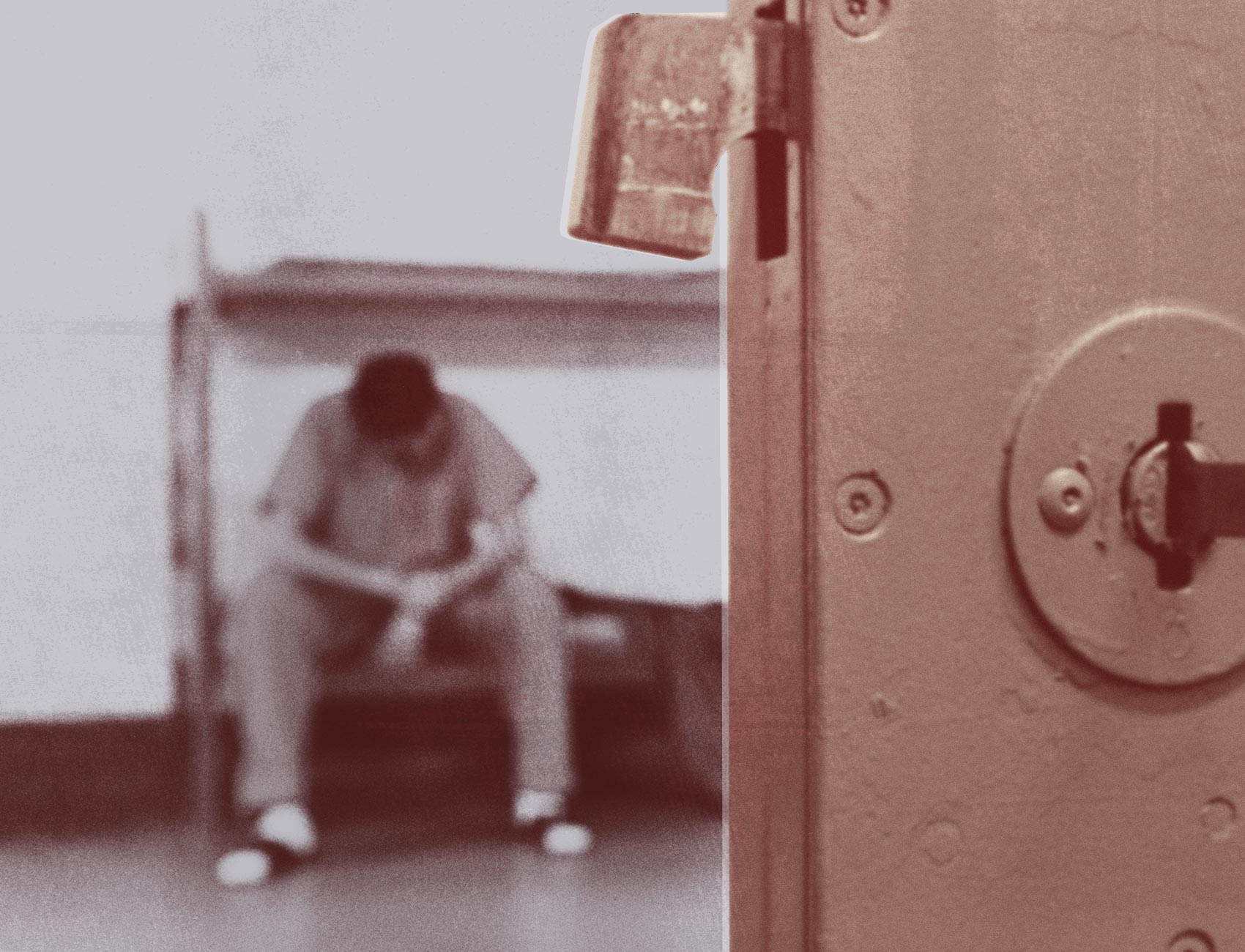

Prisons Are Overwhelmed With COVID-19. Why Aren’t Governors Doing More?

How governors respond to this pandemic will define their legacy. They all face a choice: save lives in prisons now, or hand down potential death sentences with their inaction and watch harm ripple through communities and exacerbate inequities into future generations.

This piece is a commentary, part of The Appeal’s collection of opinion and analysis.

As the Trump Administration abdicated its role in leading the fight against coronavirus, governors have emerged as critical players and sometimes media darlings — coordinating the provision of supplies, overseeing the closing and reopening of economies, and calibrating the response to the pandemic. But they have utterly failed to protect their constituents in what have emerged as the largest coronavirus hotspots — state prisons. Indeed, over half of the 84,000 coronavirus infections and 703 deaths among people incarcerated and working in local, state and federal correctional and detention facilities in the United States are in state prisons.

At a time when dense living conditions and overpopulated facilities are a ticking time bomb for spread of the virus, prisons across the U.S. have decreased their population by only 5 percent since the pandemic’s onset. Meanwhile, jails have achieved on average a 30 percent reduction in population, with some jurisdictions cutting detention rates in half or even more. That progress is attributable to many local elected prosecutors who acted swiftly with others to reduce the number of people entering jails and release as many individuals as possible. But these local leaders have limited power to impact prisons — prompting 35 district attorneys from around the country to issue an open letter and video to governors urging action. As they write, “Being confined in a prison or jail should not be a death sentence. Yet, in the context of COVID-19 that is exactly what it has become for far too many.”

The failure of governors has been universal. A recent report from the ACLU and Prison Policy Institute found gross negligence in every state, although some states have exhibited particularly egregious responses. In Michigan — where as of mid-July there have been 68 deaths and nearly 4,000 positive tests of people in state prisons — Gov. Whitmer has declined to support a ballot measure that would allow for early release of individuals incarcerated in state prisons who can be safely returned to the community. In California, Gov. Newsom recently ordered the release of 8,000 individuals, but that represents under 8 percent of an already overcrowded state prison population and a far larger number — nearly 50 percent of the population — has being classified by California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation’s own data as “low risk.” Moreover, this action comes too late to prevent the explosive and deadly outbreak at the overcrowded San Quentin prison and to save the lives of over 30 people behind bars who have died from COVID-19.

Citing public safety concerns, governors have been wary to release individuals — however that fearfulness is rebutted by evidence confirming both that many individuals can safely return home and that failing to act will result in catastrophic outbreaks in prisons with profound public health consequences for the entire community. Experts agree that there are countless individuals behind bars who can safely be released — either because they never posed a serious public safety threat or because they’ve grown and changed. The U.S. is an international outlier in incarceration and sentencing; much of the rest of the world understands that even when an individual commits serious harm, typically as a young person, that doesn’t mean that they should die in prison.

Governors can and must take immediate action, and the open letter released today calls on them to do so. They can dramatically decrease the prison population by ordering the release of elderly individuals, those with six months or less on their sentence, and those who are otherwise medically vulnerable to severe illness from COVID-19, assuming they do not pose a serious risk to the physical safety of others. They can accelerate release for individuals already found suitable for parole, suspend revocations, and terminate parole for people under supervision who have had no new criminal behavior within the last year. And finally, for those who remain incarcerated, governors should suspend co-pays for medical visits, ensure the provision of adequate medical care, provide free and ready access to phone calls with family and legal counsel, and mandate that facilities maintain cleanliness and hygiene, including by providing free soap, masks, and cleaning supplies.

It is now well-established that infections in prisons endanger the entire community. Nine of the ten biggest hot spots in the United States are jails or prisons. Prisons become wells of infection, incubating and accelerating outbreaks in the surrounding area. The failure of governors to act has already had profound public health consequences, but absent action the damage to communities will continue to escalate, while also fanning the flames of racial inequality.

The brunt of the pandemic has been borne by Black and Brown communities. Abandoning the men and women who are currently behind bars — disproportionately people of color due to mass incarceration — will only amplify existing racial health disparities. The vast majority of people in prisons will come home again, if they survive this pandemic. But they will return home, often to already medically underserved communities, with potentially life-long health complications and disabilities stemming from their infection, thereby amplifying existing inequities.

How governors respond to this pandemic will define their legacy. They all face a choice: save lives in prisons now, or hand down potential death sentences with their inaction and watch harm ripple through communities and exacerbate inequities into future generations. The answer seems clear. Let’s hope our nation’s governors agree.

Chesa Boudin is the district attorney for San Francisco, California. Miriam Aroni Krinsky is a former federal prosecutor and executive director of Fair and Just Prosecution.